The UN Human Rights Council has released its report on abuses in Syria, and it reads like a catalog of misery and disregard for human life: Arbitrary detentions and disappearances; soldiers ordered to fire on peaceful civilians, including women and children, and the execution of those who refuse; mass shootings of protesters; physical and psychological torture, including some committed in hospitals; and the violent sexual abuse of adults and children alike.

With the Arab League’s sweeping sanctions against Syria resoundingly approved this weekend, international consensus seems at last to be building against the actions of the Syrian regime. This comes not a moment too soon.

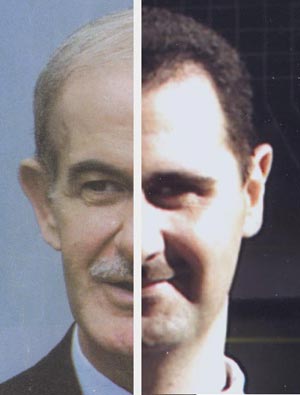

It is hard not to make comparisons to 1982 when considering the brutality of the Assad regime over the course of this year. A couple of weeks ago, I read the following tweet: “Homs 2011 = Hama 1982, but slowly, slowly.”

The Hama Massacre is infamous as one of the greatest atrocities a Middle Eastern regime has perpetrated against its own people. In 1982, the Muslim Brotherhood led a revolt centered in Hama. In response, Hafez al-Assad, father of the current Syrian despot, unleashed a brutal crackdown, killing between 10,000 and 40,000 people.

Assad’s forces pounded the city with artillery, reducing whole sections to rubble. They tortured an unknown number of citizens and executed people en masse. It took time for news of Hama to reach the outside world – in March of that year, a Time Magazine report still had the death toll at only 1,000, well below all later estimates. The total extent of Hama’s casualties will never be known.

Assad’s forces pounded the city with artillery, reducing whole sections to rubble. They tortured an unknown number of citizens and executed people en masse. It took time for news of Hama to reach the outside world – in March of that year, a Time Magazine report still had the death toll at only 1,000, well below all later estimates. The total extent of Hama’s casualties will never be known.

The people of Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen and Libya are courageous, but it must take an extra measure to fight back in Syria. In the four decades the Assads have reigned, iron-fisted repression of dissent has been the norm, with Hama the extreme example. The Syrian armed forces – more so than those in Tunisia or Egypt or Libya – are closely tied to the regime, with military leadership being drawn mostly from the Assads’ minority Alawite sect, a community that makes up about 10% of the population and could have a lot to lose should Assad fall.

More than that, it takes an extraordinary amount of courage to rise up in a country where an event like the Hama Massacre is within the living memory of many citizens, where the same regime is still in power, even if a new generation of it.

But people all over Syria have risen up – and the center of the fight this time seems to have settled on Homs. In this respect, Homs parallels Hama in 1982: it is the center of resistance for its generation, and the place bearing the brunt of the regime’s response.

It feels like reading the same story over and over, to the point where it’s an effort to remember that it is not one story being repeated again and again, but the same brutal actions being repeated by the regime again and again: 12 killed, 30 killed, 110 killed in fighting in Homs when regime tanks shelled a neighborhood, when regime soldiers attacked protesters, when regime mortars landed in a residential street.

Of the estimated 3,500 protesters killed by the security forces so far, more than 500 have been in Homs (note: the Syrian opposition puts the number killed at 4,200 with fully 1/3 of those killings being in Homs), with many more missing – whether imprisoned or dead only the regime knows. At that rate, it would take ten years for Homs to match the lowest casualty estimates for the Hama massacre, but numbers aren’t the only basis for comparison.

The point of the scorched earth policy in Hama was not the number killed or tortured or arrested. It was about making an example, about crushing the resistance, expunging it from existence so the Syrian people would know what happened to those who dared to go against the Assads.

Hafez al-Assad’s son is following the example set by his father, not just in Homs but wherever protests arise. If that was somehow unclear to anyone before, it is undeniable now with the stomach-churningly comprehensive list of abuses provided in the UN report. Bashar al-Assad has simply proceeded more slowly than his father, perhaps thinking that if he doesn’t talk about what he’s doing and keeps his abuses on a smaller scale, then it will be easier for the world to watch and wait and vacillate, intervention harder for opponents to justify, reform still on the table. He has bet that he can kill 10, 30, even 100 people at a time, and continue to talk of ‘reform’ and of fighting off ‘armed gangs of foreigners’ and get away with it.

It is no longer an option to watch and wait. Just take the case of Homs: since May, residents of the city have been killed by artillery from tanks and mortars, machine gun fire, and snipers’ bullets. Homes have been destroyed, torn apart in security raids or reduced to rubble by shelling. Security forces have made even hospitals unsafe, arresting people found seeking treatment for injuries sustained during the protests. People are taken off the streets or from their homes, some reappearing only as corpses, clear signs of torture marking their bodies.

In the last few months, there have been daily clashes in various parts of the city as citizens continue to stage protests and Assad’s forces continue to greet them with violent repression. The city is under siege, surrounded by tanks and living under threat. In the first few days after signing a peace agreement at the beginning of November, Assad killed more than 60 more of his own people, with more killed every day since then.

Bashar al-Assad is truly following in his father’s footsteps – committing brutal crackdowns designed to crush the rebellion and send an unmistakable message to others who are protesting, or who might protest in the future – but some things are different this time around. Unlike in 1982, members of the armed forces have been defecting and arming against the regime, and the really crucial difference is this: we know what’s happening this time. In 1982, Hama was in rubble, mass graves already bulldozed over, before the world knew how far things had gone. There is nothing obscuring the abuses in 2011.

Momentum seems to be building toward putting a stop to the Assad regime’s abuse of its own people, but we need to keep up the pressure. The ‘Libya Model’ of intervention may be neither practical nor strategically desirable in Syria, but there are other measures we can take and encourage other nations to take, first of them to stop treating Bashar al-Assad as a real partner while he is still killing his own people, and one nation after another seems to be doing just this in recent days.

The Arab League’s sanctions and continued condemnation of Syrian human rights abuses represent a strong step in the right direction, and a significant leap for the Arab League itself, which will have to be involved in any Syrian peace or transition of power, as will Turkey, which shares a border with Syria and has shown a clear willingness to get involved. In addition to participating in meetings with the Arab League, Turkey has been sheltering Syrian refugees and meeting with members of the opposition.

A growing number of countries have already levied economic sanctions against Syria or tightened existing sanctions, and several have made contact with Syrian opposition members. In light of this UN report, Russia and any other hold-out nations must be persuaded to stop shielding Syria from stronger action at the United Nations.

We should continue to apply pressure in the United Nations, and offer our support to all of the regional actors in such areas as humanitarian assistance to displaced Syrians and capacity-building aid to the Syrian opposition. We should make clear to oppositions leaders that we will offer aid and support to a legitimate post-Assad government, as well as immediate assistance in organizing the resistance and preparing them to handle a transition of power in the event that the Assad regime were to fall.

More than 3,500 people have already been killed in the Syrian protests, with thousands more missing or displaced. This UN report, by collating such an extensive amount of credible evidence on the Assad regime’s human rights abuses, has made it clear that the severity of the current methods of repression are a match for anything done in 1982, but there is still time to ensure that they don’t reach the scale of that atrocity.

* Caitlin Fitz Gerald writes about international affairs and civil-military relations at Gunpowder & Lead. She is currently turning Carl von Clausewitz’s On War into an illustrated children’s book. You can find her on Twitter at caidid.

CNN

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.