By: Ian Black

As reports circulate of former dictator’s death, hopes rise that nascent Libyan republic could help spread stability and reform across North Africa and Arab world.

To the west, Muammar Gaddafi was an eccentric if sometimes dangerous demagogue; but to his long-suffering people he was a capricious and cruel dictator.

In Libya, the “brother leader of the revolution” was a larger-than-life figure not because of the force of his personality, the comic opera absurdity of his uniforms or the convoluted ideas in his unreadable “Green Book” but because he barely allowed the country he ruled for 42 years to develop institutions or civil society. For all his claims to be formally powerless, he was the state.

So the lasting significance of Gaddafi’s departure is the collapse of his idiosyncratic “Jamahiriya” (state of the masses) and its replacement by a nascent Libyan democratic republic that, with luck, political acumen and lucrative oil and gas revenues, could form part of a new arc of stability and reform across North Africa.

Until the February uprising in Benghazi, the best Libya’s 6.5 million people could hope for was a future dynastic succession in which Gaddafi’s son Saif al-Islam, briefly the darling of the west, could gradually have led a process of modernisation and liberalisation from above.

But after the fall of Tunisia’s Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt – where the regimes and their institutions remain largely intact – Gaddafi’s violent overthrow reinforced the dynamic of regional change. Only neighbouring Algeria – scarred by its own bloody civil war in the 1990s – has seemed immune to the winds of the Arab spring (and appears extremely nervous about the revolution in Tripoli). In nearby Morocco, far poorer and larger than Libya, King Abdullah has already stepped up pre-emptive reforms.

Gaddafi had long lost any sympathy in the Arab world. The handsome young army officer who seized power from the western-backed King Idris in 1969 and emulated his Egyptian hero Nasser by closing down US and British bases enjoyed early popularity. But novelty quickly turned to “revolutionary” repression and he became a friendless embarrassment, the object of eyeball-rolling disdain and contempt.

The role of the Gulf states of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates in backing the Libyan opposition and engineering his departure, and the Arab League’s support for Nato action, spectacularly breached the hallowed principle of solidarity in which Arab states traditionally ignored each other’s internal affairs. The Saudis in particular hated him.

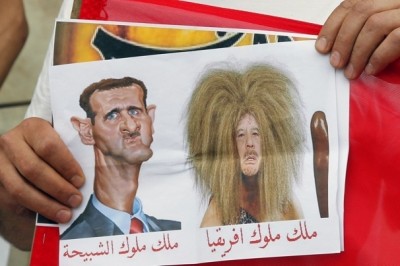

Gaddafi’s end may embolden rebels elsewhere in the region – Syria being the most obvious example. Ali Ferzat, the renowned cartoonist who had his hands broken by Bashar al-Assad’s thugs, conjured the arresting image of the departing Libyan leader offering a lift to his Syrian co-dictator. For all the differences between Tripoli and Damascus – the key one being that there is no prospect of foreign military intervention – the fall of another Arab tyrant is inspiring.

In the face of Arab hostility, Gaddafi had shifted focus in recent years to Africa, so now that he has gone Libya’s closest regional relationships should be less fraught. Still, there is lingering unease from those who saw him, for all his foibles, as a pan-African counterweight to western influence – even when, after the shock of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, he cleaned up his act and mended fences with the US and Europe.

The legacy of Libyan support for the ANC during the anti-apartheid struggle left a residual loyalty from South Africa that looked distinctly outdated as other friends and allies abandoned Gaddafi.

The man who pushed for the creation of the African Union and famously, in 2008, had himself anointed “king of kings” of the entire continent – a title that sat uneasily with his original anti-colonialist credentials – spent lavishly to secure political support and made significant investments across the impoverished Sahel.

But he also meddled in internal conflicts in Chad, Liberia and Sierra Leone and was blamed for encouraging rebellions by nomadic Tuaregs in Mali – one of few countries to see pro-Gaddafi demonstrations – as well as Niger. Still, his financial and diplomatic backing for the AU was one of the reasons why the organisation was reticent about the Libyan crisis and how to resolve it.

With Gaddafi finally out of the picture, the National Transitional Council faces a mammoth task in overseeing the change and forging a better future, with western and wider international support likely to be crucial to long-term success. For Libyans, Arabs and Africans the post-Gaddafi world may be less colourful, and, for a while, far less stable. But it is a case of good riddance: everyone should be better off without him.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.