Jack Kevorkian, the zealous, straight-talking American doctor known as “Dr. Death” for his lifelong crusade to legalize physician-assisted suicide died on Friday at a Detroit area hospital, the Associated Press reported. He was 83 years old.

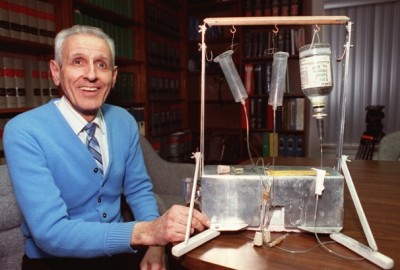

Dr. Kevorkian spent decades campaigning for the legalization of euthanasia. He served eight years in prison and was arrested numerous times for helping more than 130 patients commit suicide between 1990 and 2000, using injections, carbon monoxide and his infamous suicide machine, built from scraps for $30. Those he aided had terminal conditions such as multiple sclerosis, ALS and malignant brain tumors.

When asked in a 2010 interview by CNN’s Anderson Cooper about how it felt to take a patient’s life, Dr. Kevorkian said, “I didn’t do it to end a life. I did it to end the suffering the patient’s going through. The patient’s obviously suffering — what’s a doctor supposed to do, turn his back?”

Dying, he believed, should be an intimate and dignified process, something that many terminally ill are denied, he said.

He garnered a fair amount of support from other medical practitioners, but most believed he was an extremist. In 1995, a group of doctors in Michigan publicly voiced their support for Dr. Kevorkian’s philosophy stating that they supported a “merciful, dignified, medically assisted termination of life.”

Shortly after, a study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that many doctors in Oregon and Michigan supported some form of doctor-assisted suicide in certain cases.

One of his greatest victories was when, in March of 1996, a United States Circuit Court of Appeals in California ruled that mentally competent, terminally ill adults have a constitutional right to die with the aid of medical experts and family members. It was the first federal endorsement of its kind.

One of his greatest victories was when, in March of 1996, a United States Circuit Court of Appeals in California ruled that mentally competent, terminally ill adults have a constitutional right to die with the aid of medical experts and family members. It was the first federal endorsement of its kind.

But ultimately, Dr. Kevorkian’s impact was not in the American legal system, but in raising public awareness about euthanasia and the suffering of the terminally ill.

In the 1990s, the peak of his time in the limelight, he notoriously tried publicity stunts of all sorts to draw attention to his cause. In one instance, he showed up at trial dressed in colonial attire. He also taped one of his patient’s deaths and gave the video to the CBS News television show “60 Minutes” for broadcast. During this period, his face was constantly on television and in newspapers, and he happily agreed to a barrage of media interviews so he could share his views. His crusade and antics were documented in a 2010 HBO film, in which Al Pacino portrayed him as a passionate, but intolerably single-minded crusader.

“He was involved in this because he thought it was right, and whatever anyone wants to say about him, I think that’s the truth,” said Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania. “He didn’t do it for the money, he didn’t do it for the publicity, he wasn’t living a luxurious life – he wanted change.”

But despite his best efforts, Dr. Kevorkian was, for the most part, a lone soldier, with an abrasive personality that lived alone in a small apartment in Michigan. Though he was the most well known figure in fighting for euthanasia’s legalization, the legislative results of his efforts were largely unsuccessful, if not counterproductive.

His goal was to make it legal for a doctor to actively help a patient commit suicide. But to date, no state has made this legal and only three states, Washington, Oregon and Montana, have legalized any form of physician-assisted suicide. To the contrary, the state of Michigan, where Dr. Kevorkian did much of his work, explicitly banned physician-assisted suicide in 1993 in direct response to his efforts.

“I think Jack Kevorkian was like a flare on the battlefield — he lit up the issue and everyone paid attention,” Caplan said. “He got to absolute center stage, but he didn’t have the nuance to take it forward the way he wanted to.”

Dr. Kevorkian’s path to becoming a doctor was not as unusual as his career that followed. Born on May 28, 1928 in Pontiac, Mich., to Armenian immigrants, he originally wanted to be a baseball radio broadcaster but his immigrant parents encouraged him to pursue a more practical path. He graduated from University of Michigan’s medical school in 1952 and began a residency in pathology.

It was around this time that his peculiar obsession with death began. In the 1950s he received the nickname “Dr. Death,” when he began photographing patient’s eyes to determine their exact time of death.

He also campaigned to use the bodies of death-row inmates for medical experimentation.

And then, facing the sorrowful faces of terminally ill patients as a pathology intern, he became convinced that there was a place in the medical profession for euthanasia.

“Euthanasia wasn’t of much interest to me until my internship year, when I saw first hand how cancer can ravage the body,” he wrote in his 1993 book Prescription Medicine, The Goodness of Planned Death. “The patient was a helplessly immobile woman of middle age, her entire body jaundiced to an intense yellow-brown, skin stretched paper thin over a fluid-filled abdomen swollen to four or five times normal size.”

His life after this was entirely devoted to the cause. Dr. Kevorkian never married, and had no children, and the people most closely associated with him were his attorney Geoffrey Fieger, who represented him without fee, and one of his faithful, longtime assistants, Janet Good.

When, on one occasion, Good backed out of letting Dr. Kevorkian use her home for a suicide, he temporarily turned his back on even her.

To aid him in committing suicide, he often used his homemade machine that sent a saline drip into a person’s arm intravenously. When the patient wished to die, they could press a button that would trigger the release of a potent chemical that would put them to sleep. One minute later, a timer on the machine would send a dose of potassium chloride into the patient’s body, causing their heart to stop.

Dr. Kevorkian faced trial four times in the state of Michigan for his actions but was acquitted in three instances because of unclear laws on whether physician-assisted suicide was illegal. His fourth trial was declared a mistrial.

Unlike Michigan, most states still do not have explicit laws banning physician assisted suicide, and nearly always, Dr. Kevorkian was careful not to administer the fatal medication himself, though it was his hope that within his lifetime, the law would allow him to do so. He was thus able to escape jail prosecution for a long time.

But in 1998, when he recorded his assistance in the suicide of Thomas Youk, a man dying of Lou Gehrig’s disease, he was arrested and convicted.

Youk was too ill to administer the drugs himself, so Dr. Kevorkian did it for him and allowed the recording to be aired on the television show “60 Minutes.” Soon after, he was found guilty of second-degree murder.

During the trial, he vehemently denied any wrongdoing.

“He calls it a murder, a crime, a killing,” Dr. Kevorkian said, referring to the case’s prosecutor. “I call it medical science. Tom Youk didn’t come to me saying ‘I want to die, kill me.’ He said ‘Please help me.’ There was medical affliction. Medical service is exempt from certain laws.”

Dr. Kevorkian was sentenced to 10 to 25 years in prison for assisting Youk, but he was paroled in June 2007 for good behavior after he promised not to assist in any more suicides.

“”It’s got to be legalized. That’s the point,” he said shortly after being released from prison, to a reporter from WJBK-TV in Detroit. “I’ll work to have it legalized. But I won’t break any laws doing it.”

Ultimately, Dr. Kevorkian’s said his belief regarding a patient’s right to die had a simple premise: it was in the Constitution, unwritten but guaranteed by the Ninth Amendment which states that Americans are not excluded from rights that are not specifically enumerated in the constitution.

“There have been many constitutional scholars over time that have believed that the Ninth Amendment deserves more respect, but Dr. Kevorkian took it further than most lawyers and most constitutional scholars would take it,” said Alan Dershowitz, a Harvard professor and lawyer who was an adviser in several of Dr. Kevorkian’s legal battles, and corresponded with him while he was in jail.

“He was part of the Civil Rights movement — although he did it in his own way,” Dershowitz added. “He didn’t lead marches, he didn’t get other people to follow him, instead he put his own body in the line of fire, and there are not many people who would do that. In the years that come, his views may become more mainstream.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.