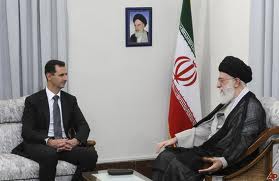

When Syria’s president visited Iran late last year, he received a heroes’ medal and spoke about unbreakable bonds in a ceremony broadcast on national television.

When Syria’s president visited Iran late last year, he received a heroes’ medal and spoke about unbreakable bonds in a ceremony broadcast on national television.

Now, a nervous leadership in Iran has imposed a media blackout on Bashar Assad’s struggle against a swelling Syrian uprising and Tehran faces the unsettling prospect of losing its most stalwart ally in the region.

The Islamic Republic managed to choke off its homegrown “Green Revolution” after the disputed June 2009 presidential election. But now it is being dragged into the uprisings sweeping across the Middle East and stirring unrest in Syria, and unfriendly neighbor Bahrain.

On the deadliest day of the Syrian rebellion Friday — when more than 100 people were killed by authorities — President Barack Obama accused Assad of seeking Iranian help to use “the same brutal tactics” unleashed against demonstrators almost two years ago.

For Iran, its ties with Syria represent far more than just a rare friend in a region dominated by Arab suspicions of Tehran’s aims. Syria is Iran’s great enabler: a conduit for aid to powerful anti-Israel proxies Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

Should Assad’s regime fall, it could rob Iran of a loyal Arab partner in a region profoundly realigned by uprisings demanding more freedom and democracy.

“Iran and Syria represent the anti-US axis in the region. In that respect, Iran wants to ensure that Syria remains an ally,” said Shadi Hamid, director of research at The Brookings Doha Center in Qatar. “The problem is that Iran’s foreign policy has become quite inconsistent.”

Iran may still have other options in the region. It has ties with Iraq’s Shiite-led government, growing bonds with Turkey and is making overtures to post-revolutionary Egypt.

But the uprisings also have sharply boosted hostility toward Iran from the wealthy — and increasingly influential — Gulf Arab states that believe Tehran is encouraging Shiite protesters in Bahrain and elsewhere.

Iran’s ambitions to expand its influence in the region could suffer a “critical backward step” if Assad’s regime is toppled, said Theodore Karasik, a regional affairs expert at the Dubai-based Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis.

“Egypt’s revolution could be considered a strategic loss perhaps for the West,” he said, “but a change in Syria would seriously rearrange the security order in the core of the Middle East and could leave Iran with an even bigger loss.”

Assessing Iran’s strategy on Syria is difficult. The ruling clerics have banned domestic media from mentioning the revolt. There have been no open debates in Iran’s parliament and leaders — including outspoken President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad — have been extremely cautious in their remarks on Syria.

Iran has used its mouthpieces to the rest of the world as forums to address Syria’s battles and promote Tehran’s positions.

State-run English-language Press TV offers straightforward coverage with comment sections that include a mix of both pro-Assad messages and calls for his regime to go. Iran’s Arabic-language Al-Alam television on Saturday quoted the foreign ministry spokesman, Ramin Mehmanparast, as rejecting Obama’s claim of Iranian aid to Assad in his time of crisis.

In a speech Saturday, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei praised the “Islamic awakening” around the region — a reference to Iran’s frequent claims that the rebellions draw inspiration from Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution. He did not mention Syria, but instead pointed to other uprisings in Libya, Yemen and Bahrain.

And, in doing so, Khamenei underscored Iran’s policy dilemma.

Iran’s leadership has harshly denounced the crackdown by Bahrain’s Sunni monarchy against the island kingdom’s majority Shiites, calling a Saudi-led Gulf force that went in to back the rulers a Sunni “occupation.” Protests in Tehran have included students hurling firebombs at the Saudi embassy earlier this month.

In response, the Gulf’s six-nation political bloc warned Iran to stop meddling in Arab affairs, and Bahrain’s foreign minister said the Gulf troops will remain indefinitely to counter Tehran’s “sustained campaign” in Bahrain, home of the U.S. Navy’s 5th Fleet.

Iran “cannot remain indifferent and passive onlookers in the face of oppressive engagement of arrogant powers with the people” of Bahrain, Khamenei told the crowds.

But no such calls have been made on behalf of Syria’s protesters, who again faced deadly gunfire by security forces on Saturday that killed 11 more people.

Iran is not the only nation balancing interests against demands for change. The U.S. has backed calls to oust Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi, but has been far more muted with the revolts in strategic allies Yemen and Bahrain. Iran also is desperate to keep its image from sustaining further blows among Arab neighbors.

“The Iranians are worrying a lot about Arab public opinion,” said Hamid. “The mood in the region is shifting against Assad and Iran could be stuck on the wrong side of that. They are sort of trapped.”

There is a way out, however, some say.

Iran is likely to open talks with opposition groups if it appears that Assad is doomed, said Meir Javedanfar, an analyst on Iranian affairs based in Israel. Iran has too much at stake in Syria to risk being cut out if Assad is ousted: huge Iranian investments in Syrian projects such as an auto assembly plant and a cement factory and possible loss of influence over Hezbollah and Hamas.

“When it comes to looking after its own interests, the Iranian regime is very pragmatic, especially since they know that Assad would do the same to them if the shoe was on the other foot,” said Javedanfar. “When it comes to choosing between friendship and its own interests, to Iran’s rulers the former is easily expendable.” AP

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.