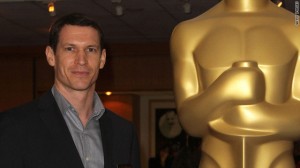

Tim Hetherington, an esteemed photojournalist and an Oscar nominee for a gritty and harrowing documentary about the Afghan war, was killed in the war-torn Libyan city of Misrata, the president of the agency that represented him said Wednesday.

Tim Hetherington, an esteemed photojournalist and an Oscar nominee for a gritty and harrowing documentary about the Afghan war, was killed in the war-torn Libyan city of Misrata, the president of the agency that represented him said Wednesday.

Other photographers were reportedly hurt in the incident that killed him. Panos Pictures, which employed Hetherington, confirmed that the photographer’s family had been notified.

“We’re still trying to figure out front lines or house,” said CSPR agency president Cathy Saypol in reference to where he was when killed. “The only thing we know is that he was hit by an RPG with the other guys.” An RPG is a rocket-propelled grenade.

Hetherington’s last Twitter entry appears to have been made on Tuesday: “In besieged Libyan city of Misrata. indiscriminate shelling by Qaddafi forces. No sign of NATO.”

A British native who was based in Brooklyn in New York, Hetherington received an Academy Award nomination this year for “Restrepo,” a documentary film he co-directed with journalist Sebastian Junger. He also worked in Afghanistan two years ago with CNN’s Anderson Cooper and Dr. Sanjay Gupta.

Vanity Fair magazine, where Hetherington was a contributing photographer, described him as “widely respected by his peers for his bravery and camaraderie.” Its profile says he had dual U.S. and British citizenship.

“We are saddened beyond words,” Saypol told Vanity Fair.

Hetherington spent eight years in West Africa and had reported on social and political issues worldwide, most notably the Liberian conflict.

He gained wide fame for “Restrepo,” which chronicles the deployment of a platoon of U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, according to the film’s website.

His website says he is interested in “creating diverse forms of visual communication and his work has ranged from multi-screen installations, to fly-poster exhibitions, to handheld device downloads.”

“The movie focuses on a remote 15-man outpost, ‘Restrepo,’ named after a platoon medic who was killed in action. It was considered one of the most dangerous postings in the U.S. military,” his website says.

“This is an entirely experiential film: the cameras never leave the valley; there are no interviews with generals or diplomats. The only goal is to make viewers feel as if they have just been through a 90-minute deployment. This is war, full stop.”

Biographical material on the “Restrepo” site says Hetherington had reported on conflict and human rights issues for more than 10 years.

“He was the only photographer to live behind rebel lines during the 2003 Liberian civil war — work that culminated in the film ‘Liberia: an Uncivil War’ and the book ‘Long Story Bit by Bit: Liberia Retold’ (Umbrage 2009), and his work for Human Rights Watch to uncover civilian massacres on the Chad / Darfur border in 2006 appeared in the documentary ‘The Devil Came on Horseback,’” his biography on the “Restrepo” website says.

In 2006, he took a break from image-making to work as an investigator for the U.N. Security Council’s Liberia Sanctions Committee, Human Rights Watch said.

“Restrepo” was his directorial debut and won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival. He has won many other awards.

“Diary,” his most recent film, is “a highly personal experimental short.”

Vanity Fair magazine said Hetherington won the World Press Photo Award in 2007 for his coverage of American soldiers in Afghanistan for the magazine.

Born in Liverpool and a student of literature at Oxford University, the 41-year-old photojournalist returned to college to study photojournalism.

Before these casualties were reported, the Committee to Protect Journalists, a watchdog group, documented more than 80 attacks on the press since political unrest erupted in Libya. Its website has a running list of attacks on media people since February 16.

“They include two fatalities, a gunshot injury, 49 detentions, 11 assaults, two attacks on news facilities, the jamming of Al-Jazeera and Al-Hurra transmissions, at least four instances of obstruction, the expulsion of two international journalists, and the interruption of Internet service. At least six local journalists are missing amid speculation they are in the custody of security forces. One international journalist and two media support workers are also unaccounted for,” CPJ said.

In one well-publicized incident, four New York Times journalists were abducted and freed last month. They described “beatings and abuse while in captivity.”

CPJ identified the journalists as Beirut Bureau Chief Anthony Shadid, reporter Stephen Farrell, and photographers Tyler Hicks and Lynsey Addario. The team’s driver, identified by the Times as Mohamed Shaglouf, is unaccounted for, CPJ said.

After Hetherington’s death, Jalal al Gallal, a spokesman for the rebels, issued a statement saying, “This is no longer the Gadhafi regime taking on Libya’s people. This is Gadhafi taking on the world. He has spared no one, not women, not children, not journalists. This is now everybody’s war.”

The fighting in Misrata — a northwestern city with an estimated population of 300,000 — symbolizes the pro- and anti-Gadhafi conflict, and the bloodshed and destruction are worse there than in other Libyan cities.

Many observers believe the besieged city is becoming like Sarajevo, the Bosnian city placed under attack by Serbian forces during the Balkan wars in the 1990s.

In fact, the office of U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay said Wednesday that some of the Libyan government’s attacks on Misrata could constitute international crimes.

A statement from the office said she condemned “the reported repeated use of cluster munitions and heavy weaponry by Libyan government forces in their attempt to regain control of the besieged city of Misrata, and said that such attacks on densely populated urban areas, resulting in substantial civilian casualties, could amount to international crimes.”

Pillay told Libyan authorities to face the fact that “they are digging themselves and the Libyan population deeper and deeper into the quagmire. They must halt the siege of Misrata and allow aid and medical care to reach the victims of the conflict,” the statement said.

“Since the city is largely cut off, it is not known precisely how many civilians have died or been injured during two months of fighting there, but it is clear that the numbers are now substantial, and that the dead include women and children,” it said.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.