By Chirine Lahoud

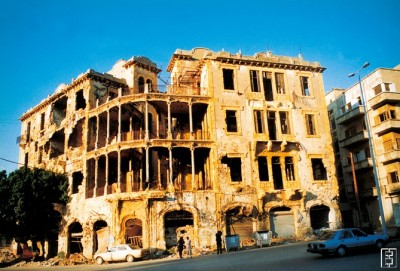

In the area of Achrafieh now called Sodeco, once known as Nasra, there sits a gorgeous ruin. Hidden behind the tarpaulin announcing future plans for the structure, the Barakat Building, also known as the Yellow House, is a rare piece of Beirut architectural history.

Because it is located along what came to be called the Green Line – the demarcation line separating “Muslim West Beirut” from “Christian East Beirut” – the structure came to be a favorite snipers’ nest during the 1975-90 Civil War.

The Yellow House emerged from that era severely damaged, seemingly fit for nothing but demolition so the land could be redeveloped – the fate of so many Beirut-area historic buildings.

But activists tried to save the Barakat Building from this fate.

Architect and preservation activist Mona Hallak dedicated 13 years of her life to saving this building from destruction and to preserve it as an important part of Beirut’s cultural history and memory. She wrote articles, lobbied politicians with petitions and organized demonstrations in front of the Barakat Building.

The building was very special when it was first erected, sometime in the 1920s, Hallak said, since its design marked it as an “avant-garde building.”

Erected on the corner of the Damascus Road and today’s Rue Eliyas Sarkis, the building forms an L-shaped structure, whose “elbow” was left open on its first and second floors.

Rare in the early 20th century, such a structural void was seen to be a modern innovation, Hallak added, since “every room had a front view onto the streets. So, there was a visual access to everyone living in the Barakat Building.”

Kozah elaborated on Aftimos’ construction in 1932 and added the concrete colonnade, nowadays heavily scarred by war damage, on the building’s southern face. This colonnade is not only aesthetically pleasing; it is characteristic of a transition (from stone to concrete) in local materials and building techniques.

As noted, the Yellow House’s function changed dramatically during the Civil War. After 1990, the most important thing about the building seemed to be how much its plot of land was worth to developers.

Between 1997 and 2003, Hallak fought to convince the government that it should expropriate the building, in order to facilitate it being re-made into a public space. After many campaigns and petitions, the Lebanese government finally acquired the Barakat Building.

Since 2008, the Yellow House has experienced a renaissance. Once doomed to destruction, it is now set to be transformed into Beit Beirut, a Museum and Urban Cultural Center scheduled to open in 2013. The objective of this project is to valorize the city’s architectural heritage with a memorial to the Civil War.

Beit Beirut will not be “a space dedicated to the dead,” said Youssef Haidar, the project’s architectural consultant, “but a memorial to [human] exchange and debates on history.”

This project is the fruit of cooperation between Beirut and Paris, who signed their first pact of friendship and cooperation in 1993. Renewed in 2006, this partnership centers on the architectural heritage and culture of Beirut. The Barakat Building was chosen to symbolize this alliance between both cities.

Architect Habib Debs, who also played an active role in efforts to preserve the structure, told The Daily Star that “for the last century, the concept of a museum [has] evolved a lot in Europe and in the U.S. And we are trying to bring that same vision to Lebanon, with the idea of opening our country to the world.”

In Haidar’s view, this project has a significant civil society aspect.

The citizens taking part in Beit Beirut wanted it to be more than just a museum, he said. They wanted it to be a space for memory, exchange, debates and exhibitions, all related to the city’s history.

The building’s first floor, he said, will be dedicated to artifacts and symbols of the war years that were found in the ruined building. Here, Najib Chemali, a dentist, left all his belongings during the war. His dentist’s chair and the remains of his clinic have been kept by experts and will be exhibited.

The same is true of the snipers’ nest and the bunkers they built in the building, then abandoned after the war.

On the other floors of Beit Beirut, visitors will find a restaurant, a boutique selling replicas of museum pieces, an auditorium (for conferences and debates), a space for workshops (presently envisioned to be dedicated to questions of memory and history and the like), and an 800-square-meter exhibition space.

Haidar says Beit Beirut will have three main axes. “First, a museum about Beirut’s memory. Second, a space on the history of the city, centered on the Civil War period. And third, a platform focusing on the question of urbanism to inform the visitors.”

“The commercial aspect of the project is very limited,” Haidar insists, adding that all revenues will be used to maintain the building and the museum.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.