A week long online campaign by Syrian activists failed to galvanize the kinds of mass protests that have rocked Tunisia and Egypt in recent weeks. In fact, no one showed up Friday and Saturday for what were to be “days of rage” against the Syrian president’s iron-fisted rule.

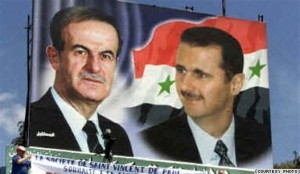

Syrian president Bashar al Assad recently boasted that his country, one of the Arab world’s most stifling regimes, is immune to the upheaval roiling other Arab countries. He was proven right …. at least for the time being.

By Saturday afternoon, the number of plainclothes security agents stationed protectively in key areas of the old city of the capital, Damascus, had begun to dwindle.

“The only rage in Syria yesterday was the rage of nature,” wrote Syrian journalist Ziad Haidar, in reference to a cold spell and heavy rain lashing the country.

But it was more than just the weather that kept Syrians at home. A host of factors — including intimidation by security agents and President Assad’s popular anti-Israel policies — kept Syria quiet this weekend.

“Syria has its own set of peculiarities that make it quite different from Egypt and Tunisia,” said Mazen Darwish, a journalist who headed the independent Syrian Media Center until it was closed down in 2009.

A major difference is that Assad — unlike leaders in Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen and Jordan — is not allied with the United States, so he is spared the accusation that he caters to American demands.

Assad, a 45-year-old British-trained eye doctor, inherited power from his father, Hafez, in 2000, after three decades of authoritarian rule. He has since moved slowly to lift Soviet-style economic restrictions, letting in foreign banks, throwing the doors open to imports and empowering the private sector.

His backing for Palestinian and Lebanese militant groups opposed to the Jewish state, as well as his opposition to the U.S. invasion of Iraq, appears to have helped him maintain a level of popular support.

Syria, a predominantly Sunni country ruled by minority Alawites, closely controls the media and routinely jails critics of the regime. Facebook and other social networking sites are officially banned, although many Syrians still manage to access them through proxy servers.

Most of the Facebook groups that called for protests are believed to have been created by Syrians abroad — which could help explain why the planned protests fell flat.

Organizers also spoke of intimidation.

Suheir Atassi, who helped organize a small vigil this week in support of Egyptian protesters, told Human Rights Watch that a plainclothes officer accused her of mobilizing people and working for Israel.

“He called me a germ. He got angry when I would answer him back, and he finally slapped me heavily on the face and threatened to kill me,” said Atassi, a longtime Syrian pro-democracy activist.

Attempts by The Associated Press to reach Atassi were unsuccessful.

Human Rights Watch also quoted witnesses as saying Syrian security forces intimidated people trying to organize support for protesters in Egypt.

The New York-based watchdog said security services arrested Ghassan al-Najjar, leader of a small group called the Islamic Democratic Current, from his home in the northern city of Aleppo on Friday, after he urged Syrians to demonstrate and press for more freedoms.

It also said a group of 20 people dressed in civilian clothing beat and dispersed the demonstrators, including Atassi, who had assembled in Damascus on Wednesday to hold a candlelight vigil for Egyptian demonstrators.

The Syrian regime has a history of crushing dissent. Assad’s father beat down a Muslim fundamentalist uprising in the city of Hama in 1982, killing thousands in the violence. In 2004, bloody clashes that began in the northeastern city of Qamishli between Syrian Kurds and security forces left at least 25 people dead and some 100 injured.

Joshua Landis, an American professor and Syria expert who runs a blog called Syria Comment, said Syrians are wary of rocking the boat and have been traumatized by the sectarian violence in Iraq.

“They understand the dangers of regime collapse in a religiously divided society,” he wrote in a recent posting.

Syrian state-run newspapers have reported extensively on events in Egypt, suggesting Syria may be feeling vindicated.

An editorial this week in the Baath newspaper, mouthpiece of the ruling party, said the uprising in Egypt is proof that all the troubles of the Arab world stem from “the complete acquiescence of some (Arab) regimes to the U.S. and their acceptance to take Zionist dictates.”

Assad told The Wall Street Journal in an interview published Monday that Syria is insulated from the upheaval in the Arab world because he understands his people’s needs and has united them in common cause against Israel.

A 17-year-old student, Tayyeb, said some Syrians have legitimate grievances against the government.

“But I am against staging such mass protests,” said Tayyeb, who asked that only his first name be used because of security concerns. “Look at what’s happening in Egypt, it’s total chaos.”

Wrong lesson

Playing to the popular anti US and Israeli sentiments won’t keep Assad immune from the massive changes sweeping the region, says Nadim Houry, Human Rights Watch’s researcher for Syria and Lebanon. “If the lesson Assad takes from Egypt is that it’s all about foreign policy, he is learning the wrong one.” Mubarak’s policy towards the U.S. and Israel was just one grievance on a long list for the protesters, but it wasn’t the main one. While the occasional anti-Israel slogan could be heard at Tahrir Square, it was largely drowned out by demands for better treatment and dignity. “The main grievance was the daily humiliation at the hands of the security services,” says Houry. “It was about the corruption, the lack of economic development. And those elements are all present in Syria.”

CP, Time

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.