By: NIRAJ WARIKOO

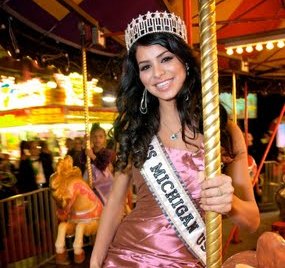

Draped in a Guess dress, Rima Fakih glided across the lawn of her parents’ home in Dearborn on a Friday night to greet her guests.

“Ahlan!” she exclaimed to a cousin, using the Arabic word for “hello.”

“How are you?” she then asked a friend in English, beaming.

The blending of cultures — Arab and American — was evident at Fakih’s farewell party two weeks ago as she prepared to leave for Las Vegas, where she is to compete Sunday in the Miss USA beauty pageant. The Dearborn resident with roots in Lebanon hopes to become the first Miss USA who is Arab American. If she wins, she would be the second Michigander to make history: In 1990, Carole Anne-Marie Gist became the first African American to win Miss USA.

“It’s OK to be proud of who you are,” Fakih, 24, said inside the living room as her grandmother watched a Lebanese TV station.

But even though Fakih isn’t shy about her Middle Eastern ancestry, Miss Michigan 2010 said she’s prouder of her state. She hopes to sport clothes by Michigan designers Sunday.

But even though Fakih isn’t shy about her Middle Eastern ancestry, Miss Michigan 2010 said she’s prouder of her state. She hopes to sport clothes by Michigan designers Sunday.

“I want to let people know that Michigan has a lot to give,” she said. “I want to help take Michigan to a different level.”

Party illustrates diversity

“Rima, you have a beautiful face,” the singer croons in Arabic to a sinuous melody from a keyboard. “I would never refuse any of your requests — even if you asked for my soul.”

The scene at Rima Fakih’s send-off party two weeks ago illustrated the diverse backgrounds that make up her persona, which she hopes will bring the Miss USA crown to Michigan on Sunday.

As an Arab American, Fakih’s story contains the tensions and hopes of a metro Detroit community that has been in the spotlight during the last decade as it battles stereotypes from without and within.

Given the community’s cultural conservatism, some Arab Americans — in particular, Muslims — aren’t keen on seeing their daughters and sisters participate in beauty pageants that feature public displays of the body.

But the virtue of physical beauty in women and men has a long tradition in Arab culture, historians say. And many have enthusiastically supported Fakih, saying she represents the confident face of a new generation of Americans with roots in the Middle East. Several Arab-American and Lebanese organizations in Dearborn have even helped her finance previous pageant competitions in the hope that Fakih will be a positive face for their community.

“My father always says, ‘You don’t know who you are until you know where you come from,’ ” says Fakih, 24. “I believe in that.”

Beauty on display

The cultural tensions were highlighted this week as the Miss USA pageant released photos of all 50 contestants, including Fakih, in sultry poses on beds wearing lingerie and little else.

In her pageant photo, Fakih gazes at the camera, her fishnet stockings held up by a garter belt as her black hair falls across her side.

It would be a revealing photo for anyone. But perhaps even more so for Fakih, given that she’s an Arab-American Muslim from Dearborn.

Fakih is aware that some in metro Detroit’s Middle Eastern communities may object to women parading their beauty, but she said her family supports her. In fact, her mother encouraged her to compete.

“I think the community in Michigan, in Dearborn, might be a little on the strict side,” Fakih said. “But my family, in general, are not.”

The photographer who shot the provocative images, Fadil Berisha, also happens to be a Muslim and is an immigrant from Albania. He defended the photos, saying that his interpretation of Islam and his culture would allow for such poses.

“The bottom line is, art is art,” Berisha told the Free Press. “As long as it’s done tastefully, it’s fine. We’re not here to be priests or imams.”

Family and community support

With roots in south Lebanon — a region many in Dearborn have ties to — Fakih’s family moved in the early 1990s to Queens, N.Y. There, the family lived through the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

A student in a Catholic high school at the time, Fakih remembers stories of teachers and friends losing loved ones that day. She said she recalled one student ribbing her about being “the enemy,” but her friends stood up for her, and she didn’t feel any backlash.

A student in a Catholic high school at the time, Fakih remembers stories of teachers and friends losing loved ones that day. She said she recalled one student ribbing her about being “the enemy,” but her friends stood up for her, and she didn’t feel any backlash.

After she graduated from high school, Fakih and her family moved in 2003 to Dearborn, known for having one of the highest concentrations of Arab Americans in the U.S. Relatives say she was always a tomboy, playing football with the boys and excelling in volleyball and basketball in school.

Her mother was the one who encouraged her to compete in beauty pageants, partly as a way to earn scholarship money. “When I did my first pageant, my mom was so happy. She was like … ‘My daughter is a princess again,’ ” Fakih said with a chuckle. Today, she works in marketing at the Detroit Medical Center, with plans for law school.

For previous pageants, Fakih sought — and received — support from Arab-American leaders in Dearborn, including Imad Hamad, head of the Michigan branch of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. His group helped once support Fakih financially, despite opposition from some who felt pageants are “not something they wish to see,” Hamad said.

But “our youth deserve every bit of support,” Hamad said. “It took a great deal of passion, guts, courage and self-confidence to compete for a title like this.”

Challenging stereotypes

Moreover, Lebanon is a country that tends to be more open toward events such as beauty pageants, compared with other Arab countries, Fakih and other Arab Americans say. In Lebanon, “watching the Miss Lebanon pageant is like watching the Super Bowl,” Fakih said.

Fakih also can help counteract stereotypes of women in the Middle East, Hamad and Fakih’s family members say.

“This will show the good part of Arab Americans,” said Fakih’s brother Rabih Fakih, 37. “A lot of people think this area of the world is only about people being covered.”

Others, though, see the covered woman as a positive aspect of Arab and Islamic identity that makes them unique and moral. In recent decades, beauty pageants in the Arab world have met with increasing resistance with the rise of religious fundamentalism, said Doris Behrens-Abouseif, a professor at the University of London in England and author of “Beauty in Arabic Culture.” Some Islamic scholars have issued fatwas, religious edicts, urging women not to participate in such contests.

But to Rima Fakih and her many supporters, such thinking ignores the multicultural mixing of the modern world.

Picture of Arab diversity

The scene at Fakih’s party was a tableau that illustrated the diversity among Arab Americans and Fakih’s circle. There were women wearing hijabs, Islamic headscarves that symbolize modesty, chatting with other women sipping red wines. Others puffed on hookahs between bites of a raw lamb dish, kibbe. There were Christians and Muslims, Poles and black people, Lebanese and white people, all there to wish Fakih the best in Las Vegas.

Fakih’s family is itself a blend of cultures and religions, including both Christians and Muslims. Though Muslim, Fakih’s parents celebrate Christmas and have a painting of Jesus in their home.

Near the end of the party, as guests nibbled on Lebanese pastries, her parents gushed about their daughter.

“I’m sure she’s winning,” declared her father, Hussein Fakih, 66. “She’s the queen.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.