By: Elias Muhanna

This Sunday, a group of Lebanese citizens will take to the streets of Beirut to demonstrate their support for secularism. No one knows how many people will show up, but this is a country that has grown accustomed to the pageantry of public demonstrations, and so a crowd of several thousand is not unlikely. Plus, the weather forecast looks promising: no rain, hazy skies and warm temperatures. In short, perfect conditions for strolling through a crowded square, waving a banner and chanting slogans.

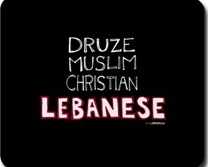

The question of what it is that people will be chanting is of particular interest. Will they call for the dismantling of Lebanon’s system of political confessionalism, which divides power between different religious communities? Or will they demand the separation of religion from personal status matters, such as marriage and inheritance laws? Some may carry banners denouncing the intrusion of religious figures – priests and muftis, bishops and mullahs – into the realm of politics. And some may just come along for the ride, unsure of what exactly “secularism” means in the context of a country like Lebanon, but certain that it must be better than what we have now.

I count myself in this latter category of open-minded observers, deeply dissatisfied with Lebanon’s system of governance and the sectarian logic at its heart, but uncertain of how to go about replacing it.

Since independence in 1943, Lebanon’s president has always been a Maronite Christian, its prime minister a Sunni Muslim, and its speaker of parliament a Shia Muslim. Within parliament, seats are divided equally between Christians and Muslims, and even high-level civil service posts are filled according to tortuous sectarian formulas.

This system, which was once upheld by scholars as a successful symbol of consensual democracy and religious coexistence, has long since demonstrated its failures – including chronic instability, gross inequalities of suffrage, frequent paralysis, and a central government so weak as to be incapable of providing basic services, security, and transparency.

Recent polls have shown that there is significant public support for abolishing the confessional system in Lebanon, but, like many issues, this is also influenced by a sectarian calculus: most of the support lies among Lebanese Muslims, whose numbers relative to the Christian population have grown over the past several decades. Many fear that trying to impose sweeping changes on the country without the support of a majority of the Christian community could have severe repercussions. Finally, of all the participants surveyed in the above-mentioned poll, nearly a quarter said that they did not know what “abolishing confessionalism” even meant.

And this really is the crux of the matter. Previous efforts by Lebanese civil society groups to push a secularist agenda have failed largely because of the ambiguity of their ideas.

While almost every major political party in Lebanon has, at one point or another, paid lip service to the ideal of a meritocratic system of government free from sectarian quotas, there have been all too few concrete proposals for how such a system would function and the process needed to produce it. The current initiative behind the Lebanese Laique Pride march on Sunday seems destined to suffer the same fate as its predecessors: a brief, hopeful moment of energy and goodwill, followed by a quiet death on the op-ed pages of a handful of Lebanese newspapers.

I hope, desperately, to be proven wrong. But until the language surrounding this issue becomes more precise, nuanced, and reality-based – language that, alas, does not lend itself so well to banners and slogans – the prospect of a secular Lebanon will remain a distant vision. guardian.co.uk,

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.