By Joby Warrick

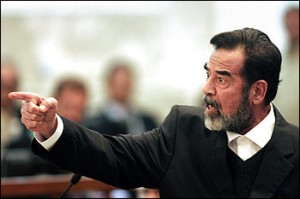

As troops massed on his border near the start of the Persian Gulf War, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein weighed the purchase of a $150 million nuclear “package” deal that included not only weapons designs but also production plants and foreign experts to supervise the building of a nuclear bomb, according to documents uncovered by a former U.N. weapons inspector.

The offer, made in 1990 by an agent linked to disgraced Pakistani scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan, guaranteed Iraq a weapons-assembly line capable of producing nuclear warheads in as little as three years. But Iraq lost the chance to capitalize when, months later, a multinational force crushed the Iraqi army and forced Hussein to abandon his nuclear ambitions, according to nuclear weapons expert David Albright, who describes the proposed deal in a new book.

Iraqi officials at the time appear to have taken the offer seriously and asked the Pakistanis for sample drawings as proof of their ability to deliver, the documents show. “With the assurance of [Iraqi intelligence agency] Mukhabarat . . . the offer is not a sting operation,” an Iraqi official scrawls in ink in the margin of one of the papers.

Khan’s alleged interest in selling nuclear secrets to Hussein has been reported in numerous books and news articles. An internal Mukhabarat memo that surfaced in the late 1990s discussed a secret proposal by one of Khan’s agents to sell a nuclear weapons design for an advance payment of $5 million.

But the newly uncovered documents suggest that Khan’s offer of nuclear assistance was more comprehensive than previously known. A 1990 letter attributed to a Khan business associate offered Iraq a chance to leap past technical hurdles to acquire weapons capability.

“Pakistan had to spend a period of 10 years and an amount of 300 million U.S. dollars to get it,” begins one of the memos. “Now, with the practical experience and worldwide contacts Pakistan has developed, you could have A.B. in about three years’ time and by spending about $150 million.” “A.B.” was understood to mean “atomic bomb,” Albright wrote in “Peddling Peril: How the Secret Nuclear Trade Arms America’s Enemies,” released this week.

At the time of the 1990 offer, Iraq was embarked in a crash program to develop nuclear weapons in the face of a threatened U.S.-led attack over its occupation of Kuwait. By that date, Iraqi scientists had acquired a limited amount of weapons-grade enriched uranium but lacked several key components, including a workable design for a small nuclear warhead.

Fears that Iraq had reconstituted its nuclear weapons program helped propel the United States into a second war with Iraq in 2003, though a U.S. review later determined that Hussein was never able to mount a serious bid for the bomb after 1991.

Aid from the Pakistani scientist could have accelerated Iraq’s quest for a weapon if the Iraqi leader had not run out of time, writes Albright, a former U.N. inspector who now heads the nonprofit Institute for Science and International Security. One memo cited in the book promised to provide “all the vital components and materials” needed to make fissile material, and added that “two to three Pakistani scientists could be persuaded to resign and join the new assignment” in Iraq. Copies of the original Arabic documents — several with handwritten comments in the margins — were shown to The Washington Post.

The alleged nuclear offer to Iraq is broadly similar to proposals Khan reportedly made to Libya and Iran during the 1980s and 1990s. Khan, who is celebrated in his country as the father of Pakistan’s atomic bomb, was placed under house arrest in 2004 after he acknowledged his role in an international smuggling ring for nuclear technology. Pakistan says Khan acted alone in seeking to sell his country’s nuclear secrets. But Khan, in a series of memos and letters obtained by The Post, says he carried out the instructions of senior government and military officials.

In his book, Albright argues that Khan could have been stopped if governments and private businesses had been more willing to share intelligence. He cites results of a secret Dutch investigation into Khan’s activities in that country in the 1970s, a probe that confirmed Khan’s theft of sensitive nuclear blueprints, yet failed to result in a broader inquiry of a serious security breach.

“One of the very few early opportunities to stop him was lost,” he writes.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.