- Iraq’s political parties will have to balance the financial and political support they accept from external patrons such as Iran, Turkey and the Gulf states with the kind of nationalism voters in the country increasingly demand.

- To that end, Iraq’s major Shiite parties will try to downplay their ties to Iran and promote anti-corruption measures.

- Iraqi politicians, meanwhile, will form new coalitions across party and sectarian lines in an effort to maximize their appeal to voters ahead of the 2018 legislative and provincial elections.

In Iraq, domestic politics are an international affair. The multiplicity of interest groups represented in the country’s central government — meant to ensure a degree of inclusiveness in the wake of Saddam Hussein’s repressive administration — complicates coalition building, leaving room for nearby states to insert their own competing agendas. Regional powers such as Turkey, Iran and the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council lend financial and political support to many Iraqi parties, and, where applicable, to their affiliated militias.

But as provincial and parliamentary elections, tentatively scheduled for 2018, approach in Iraq, their help may not be as welcome as it once was. Now that Iraqi forces have reclaimed Mosul from the Islamic State, the government in Baghdad has a unique opportunity to move the country forward, free of the security woes that previously hamstrung it. As part of that effort, many politicians are championing nationalism, condemning corruption and rejecting external influence to satisfy popular demand from sectarian and ethnic groups. Iraqi politics are evolving and, with them, the relationships between foreign powers and domestic parties.

Changing Allegiances

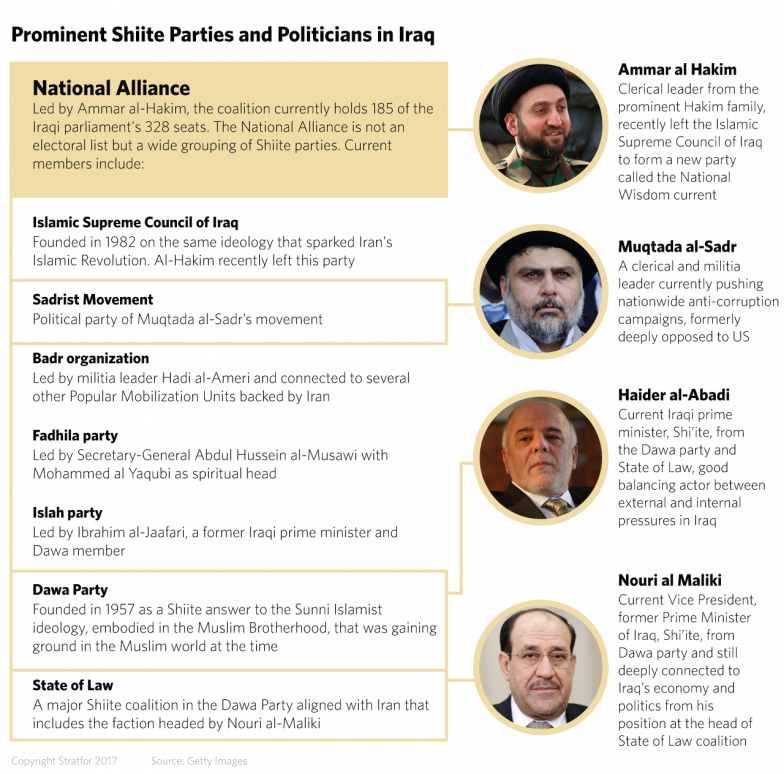

A shift is underway in Iraq’s Shiite community. In the past month, the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI) — a cornerstone Shiite party founded in 1982 on the same principles that sparked the Iranian Revolution — lost its leader, Ammar al-Hakim. Al-Hakim finally broke with the ISCI in July, after years of escalating disagreements with the party’s three other heads. Without wasting any time, he formed a new group, the National Wisdom party. The split is part of al-Hakim’s attempt to stay competitive ahead of the upcoming elections by courting younger voters and building up his nationalist credentials. And the effort may well pay off; al-Hakim, after all, is heir to a powerful and well-connected Shiite clerical family in Iraq. The new party could bode ill for the ISCI’s performance in the next elections. Iran, however, is confident that its deep ties to the al-Hakim family will continue to serve its interests in Iraq, even if National Wisdom and its leader try to downplay their connections with Tehran.

The ISCI isn’t the only Shiite party in the throes of a factional dispute, either. Rival party Dawa is also experiencing internal conflict that could threaten its prospects in 2018. Since 2006, Nouri al-Maliki (then Iraq’s prime minister) has led Dawa’s most powerful faction. But his pro-Iran, anti-U.S. stance has left the party divided. Iraqi Prime Minister al-Abadi, for example, reportedly has been considering peeling off from Dawa to form a so-called Liberation and Construction party. The prospective group, named for al-Abadi’s success against the Islamic State, would be a rejoinder to State of Law, a coalition that al-Maliki formed in 2009 (whose name reflected his own victory establishing law and order after the chaos of the mid-2000s).

Though al-Abadi has denied rumors of a new party, the rivalry between him and al-Maliki will grow as the 2018 elections approach. The former prime minister has toured predominantly Shiite provinces in Iraq to improve his standing among the sect’s members while also working to polish his credentials with trips abroad, for instance to Russia. Al-Maliki has criticized al-Abadi during his travels, leveling accusations of corruption and malfeasance. At the same time, however, he can’t afford to lose al-Abadi’s membership in Dawa and the support base the prime minister has to offer the party. Should al-Abadi strike out on his own in the next elections, the defection will be a clear attempt to distance himself from al-Maliki and the Iranian influence he represents.

Building Bridges to Power

Despite the factional strife besetting them, the parties’ massive Shiite National Alliance coalition is still holding together. Partnerships within the Shiite camp will start emerging with increasing frequency, moreover, as parties try to appeal to the most voters possible ahead of the elections. Controversial Shiite leader Muqtada al-Sadr recently announced an agreement between his Sadrist Movement — a nationalist party — and the al-Watniya coalition led by Iyad Allawi, a former prime minister and current vice president of Iraq.

As it stands, the Shiites have enough electoral clout to overcome challenges from Kurdish and Sunni Arab parties in parliament. But that hasn’t kept them from trying to build coalitions with these parties to further shore up their legislative power. Shiite leaders from al-Hakim, al-Maliki and al-Abadi to al-Sadr have made overtures to Arab Sunni and Kurdish parties in hopes of forging deeper ties. Al-Sadr demonstrated his eagerness to tap into the Sunni voter base recently by accepting invitations to visit with the crown princes of Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi. The Sadrist Movement isn’t as close to Iran as many of its fellow Shiite groups are. And for Riyadh, the party represents a way to gain access to Iraq’s political scene and to undermine Tehran’s creeping influence in the country. In addition, forging ties with the Sadrists could offer the Saudi government a means to build a more constructive relationship with its own Shiite community.

Gearing Up to Vote

Iraqi’s Arab Sunni parties, meanwhile, are stuck playing catch-up as usual with their Shiite counterparts, which have the advantage of a larger and more powerful voter base on their side. To that end, a group of Sunni parties unveiled the Iraqi National Forces Alliance in July. The new coalition comprises 300 Sunni figures, including deputies and tribal leaders from provinces once controlled by the Islamic State, under the leadership of Salim al-Jabouri, a prominent Sunni leader and speaker of Iraq’s House of Representatives. Each of the bloc’s constituent parties has strong local support and receives external aid to one degree or another from Sunni powers in the Middle East such as Turkey and the Arab Gulf states. As the elections approach, however, many of the groups are trying to distance themselves from their sponsors abroad in an effort to ride the wave of Iraqi nationalism. The new coalition is meant to give Iraqi Sunnis a fresh start since an attempted conference to discuss their future, and that of their country, fell through — partly because of controversy over the Sunni parties’ foreign backers.

As for Iraq’s Kurdish community, a largely Sunni constituency whose presence in parliament roughly matches that of the Arab Sunnis, ties with foreign governments are causing problems. The Kurdish groups are at odds about an impending referendum to decide whether Iraqi Kurdistan should declare its independence from Iraq. Adding to the tumult, the United Arab Emirates recently increased its financial and political support to the Kurdistan Democratic Party, which is not only Iraqi Kurdistan’s ruling party and the most powerful Kurdish party in parliament, but also the referendum’s chief proponent. The United Arab Emirates threw its weight behind the vote, slated for Sept. 25, as a jab at Iran and Turkey, countries that strongly oppose the establishment of a more autonomous Kurdish state.

A Long Campaign Ahead

As Iraqis prepare for the fourth legislative elections since 2003, their country’s security situation, albeit much improved, is still precarious. The Independent High Electoral Commission has deemed dozens of districts in Iraq, most of them in Sunni territory, too unstable to conduct necessary preparations for the votes. (Lingering security concerns are the main reason the provincial and parliamentary elections will probably be held at the same time.) Furthermore, Iraq’s sitting lawmakers still need to hash out a new electoral law before the votes can take place, after which the commission will need about six months to finalize plans for them.

In the meantime, though, the coalition building efforts will continue, offering a glimpse into the alliances that will emerge after the elections. That’s when the true power struggle between al-Maliki, al-Abadi and al-Hakim will start as they vie to secure the prime minister’s post — Iraq’s premier political office — for their chosen candidate. According to the Iraqi Constitution, the newly elected parliament is responsible for choosing a presidency council, which then selects the country’s prime minister. The party that wins the most seats in the legislative elections will exercise that mandate when selecting the prime minister. Between now and then, Iraqi parties across the political, ethnic and sectarian spectrum will try to strike a balance between satisfying nationalist voters and satisfying the foreign backers they depend on for support.

STRATFOR

Note to Ya Libnan readers

Ya Libnan is not responsible for the comments that are posted below. We kindly ask all readers to keep this space respectful forum for discussion

All comment that are considered rude, insulting, a personal attack, abusive, derogatory or defamatory will be deleted

Ya Libnan will also delete comments containing hate speech; racist, sexist, homophobic slurs, discriminatory incitement, or advocating violence, public disorder or criminal behavior profanity , crude language and any words written in any language other than English.

Analysis: Tipping the scales of political power in Iraq

Highlights

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.