By Florence Fabricant

After more than 30 years of civil war, invasion and occupation, Lebanon is prospering again, and the downtown area of Beirut, the capital, has risen from the rubble.

Among more than 400 projects are a new waterfront area, parks, world-class hotels, high-end shops and restored monuments, churches, mosques and even the synagogue.

And to help the city reclaim its title as the Paris of the Middle East are more than 100 restaurants, some involving notable chefs and restaurateurs.

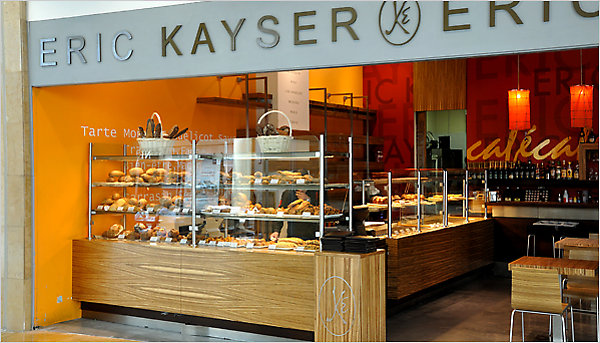

Joël Robuchon, Yannick Alléno, Antoine Westermann, the Parisian baker Eric Kayser and perhaps even Jean-Georges Vongerichten are among the marquee names poised to draw tourists and cosmopolitan locals to the once devastated quarter.

But while some Lebanese might dare to try Mr. Robuchon’s eel with foie gras, when it comes to their own cuisine, tradition rules. You’ll find croissants seasoned with the spice blend zataar in bakeries, but that’s about as far as most chefs dare to innovate. A few restaurants are adding Asian or Mexican dishes to Lebanese menus, but generally it’s hands off when it comes to classics like hummus.

Lebneniyet, a Lebanese restaurant in the rebuilt area, prides itself on authenticity rather than creativity.

“The Lebanese like routine — it’s comforting after what they have gone through,” said Philippe Massoud, the chef and owner of Ilili in New York, who is from Beirut but who left during the civil war.

The dozens of cold and hot plates that come under the heading of meze — like hummus, tabbouleh, fattoush, eggplant purées, little grilled sausages, savory filled pastries, assorted kibbees and the like — are appreciated according to the finesse of the preparation.

“Nouvelle Lebanese does not exist,” said Kamal Mouzawak, a writer who became a food activist and now supports small farmers and regional cooking traditions with a farmers’ market and a restaurant in Beirut. “Food like you get at Ilili in New York would be shocking to the Lebanese — duck shawarma and things like that,” he said, referring to the popular sandwich made in Lebanon with shavings of spit-roasted beef or chicken. “Right now we are discovering our traditions. During the war and its aftermath we were too busy with other things.”

Restaurants serving Lebanese food are now starting to feature ragouts, often vegetable-based, that typically were served only at home. Comfort food, yet something new.

“It’s like a food museum every day,” Mr. Mouzawak said.

Every five weeks, reservations are at a premium when Joe Barza, a burly goateed chef who is an outspoken advocate of new Lebanese cuisine, cooks lunch at Tawlet. “Why does hummus have to be made with tahini?” he asked at lunch there a few weeks ago. “I see a big opportunity.”

His buffet included hummus made with broad beans instead of the usual chickpeas, enough of a departure. Kibbee was made with raw fish, not raw meat. And a dish called siyadieh, which usually combines fish with rice, was done with frik, a roasted green wheat that is cooked like a pilaf.

“We have the ingredients,” Mr. Barza said. “We just have to think about how we are using them.”

Lebanon’s larder is extremely rich. Almost anything, including American beef, can be imported, and even pork is sold, a rarity in an Arab country. In the countryside, farmers set up impromptu stands along the roads with gorgeous fresh favas, green beans, strawberries and artichokes. The produce at Souk el Tayeb, the farmers’ market that Mr. Mouzawak has organized on Saturday mornings in downtown Beirut, is nothing short of mouthwatering.

Fish restaurants like Chez Sami, which overlooks the sea just north of the city, display beautiful, mostly local catches that are simply fried or grilled. And yet the array has its limitations.

“Lebanon has some terrific ingredients they don’t use, like sardines,” said Mourad Mazouz, an owner of restaurants in London and Paris, who is on track to open in the newly developed area with a Moroccan-French-Lebanese menu. Both Mr. Robuchon and Mr. Alléno said they were going to try to use as many local ingredients as possible.

Unlike the restaurants, Lebanon’s wineries are trying some new approaches to build on a tradition that is said to go back 5,000 years.

Ixsir, a new winery near Byblos, north of Beirut, is selecting grapes from farmers in several regions to find the best terroirs, according to Étienne Debanné, the owner. Massaya, in the Bekaa Valley, is experimenting with tempranillo, the red grape of the Rioja region in Spain, and it is making a white wine with a blend that includes obeidi, the native grape said to be a precursor of the French clairette. The unusual white wines of Château Musar, perhaps the best-known Lebanese label, have always been made with native grapes.

“We’re more behind the scene when it comes to experimenting with our food than with our wine,” said Naji Saikali, the brand manager for Ixsir. “We hesitate to innovate. Perhaps it’s because we’re living with risk. But you can’t always postpone trying something new because you’re afraid something may happen to disrupt your life.”

The New York Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.