By: RICHARD ENGEL

Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan was quoted Monday as saying that Russian President Vladimir Putin may be ready to “give up” on Syrian President Bashar Assad.

“(Putin) is no longer of the opinion that Russia will support Assad to the end. I believe he can give up Assad,” Erdogan was quoted as saying in Turkey’s Daily Sabah newspaper.

Russia has been one of Assad’s most loyal backers and it had its reasons. Moscow wants to maintain its access to a warm water port in Syria and has long made it clear that it does not support U.S.-led regime change in the Middle East, believing it created mayhem in Iraq and Libya.

So a change of Russia’s position on Assad would be significant. But is it wishful thinking?

Erdogan denounces the Assad regime at every opportunity. Could Erdogan be trying to put words in Putin’s mouth hoping to undercut his enemy Assad?

It doesn’t appear so. A senior U.S. official and a diplomat posted to Moscow both tell NBC News Russia is indeed looking beyond Assad and his inner circle.

“Russia is looking at other options,” said the U.S. official who is involved in formulating American foreign policy in the Middle East.

“The Russians don’t see [Assad] as the only option anymore. They’re showing more flexibility,” added the Moscow-based diplomat from a U.S.-allied country who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he is not authorized to speak to the media.

“The Russian [government] would be willing accept an off-ramp for Assad, say a six-month transition, but then to what? They [the Kremlin] want to know the road map, what the next step leads to, what happens next?” the diplomat said.

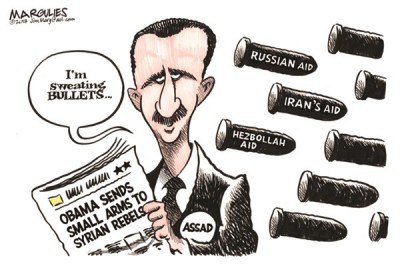

But the Russians aren’t Assad’s only powerful backers.

“The question now is the Iranians. Will they keep insisting on Assad or show more flexibility now that their dynamic is changing” with the nuclear deal, said the U.S. official who also spoke on the condition of anonymity because he is not authorized to speak to the media.

Some in Washington, he said, are looking to Iraq where Iran had a favorite politician but was able to see him leave office without Tehran losing influence.

“Look at the example of [former Iraqi prime minister Nouri] al-Maliki. Iran used to insist on him and have now adjusted to an Iraq without Maliki,” he said.

Tehran backs Assad for very different reasons to Moscow’s. It sees Syria as part of Iran’s regional sphere of influence, an essential bulwark of a Shiite front, even though the Syrian regime and Iran do not follow the same strain of Shiite Islam.

If both Russia and Iran pulled their safety nets out from under Assad, the regime would likely be severely weakened. The Syrian regime’s lone remaining backer would be the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah.

“Hezbollah is finding the fight in Syria a bigger drain than it expected,” the U.S. official said. “They’re mostly there because Iran demands it.

The Israeli website ynetnews reported in July that Hezbollah had lost some 1,300 fighters in Syria. Hezbollah’s commitment to Syria has been more extensive than it bargained for.

The Israeli website ynetnews reported in July that Hezbollah had lost some 1,300 fighters in Syria. Hezbollah’s commitment to Syria has been more extensive than it bargained for.

All three, Russia, Iran and Hezbollah — like the US and Europe — share an interest in weakening ISIS, and the biggest factor drawing in ISIS recruits has been the Syrian war itself. Dry up the war, dry up ISIS.

ISIS sees Iran, a Shiite powerhouse, as an eternal and permanent enemy. Russia worries about the growing numbers of its nationals from the caucuses — Dagestan, Chechnya, Ingushetia — going to fight with ISIS and bringing the jihad home. Hezbollah wants to end what is an unnecessary drain on its capacity in Syria.

The U.S. official insisted that discussions about a post-Assad Syria are only at “early stages” and that this “may not progress in a linear way,” diplomatic speak for it will be messy and complicated.

In its most basic form, a deal to off-ramp Assad sounds simple: Russia and Iran would withdraw their support for Assad and a group of his inner circle, “the ones with the most blood on their hands,” the U.S. official said.

Assad and his closest cohorts would most likely be given safe passage to a third country with guarantees of immunity, according to the Russia-based diplomat.

Assad’s exit could then open the door to talks with the Syrian opposition to form a new government. A transition period would be set. Many core elements of the old regime would be kept. Amnesties would be offered on both sides. Money would be pledged to rebuild. A deal for a political transition would likely be endorsed by the U.N. and other international bodies. Then, on the battlefield, the United States, Russia, Iran and others nations enduring the new political process could fight together against ISIS, instead of the kabuki dance that is the war on ISIS now.

Will it work? It will be hard, but after so many years with no light at the end of the tunnel, any glimmer can be important.

NBC NEWS

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.