By: Joyce Karam, Al Hayat

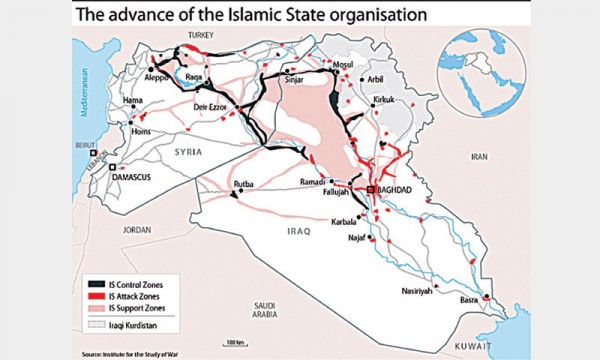

When Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi , the leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) flaunted a year ago from the Great Mosque in Mosul the birth of his new “Caliphate,” it was both a statement of the organization’s brutal ambition and the unraveling of the Sykes-Picot map in both Iraq and Syria.

One year later, ISIS as a non-state actor and a terrorist organization is the loudest but not the only symptom of the de facto crumbling of the central nation state structures in Baghdad and Damascus. Understanding its threat and prospects cannot occur absent of this context of rising militias and autonomous groups in what was once “the beating heart of Arab nationalism.”

End of Sykes-Picot?

One century into the Sykes-Picot agreement, which drew the modern borders of the post-Ottoman Middle East, the geography and future of the British-French map is dissolving, as a sectarian inferno takes over Iraq and a war of attrition and proxy sees no end in Syria.

The ISIS caliphate that Baghdadi in his black turban and robe declared in Mosul last year is one byproduct of the disintegration of the nation state in Iraq and Syria. The Iraq war in 2003, and the deeply flawed Debaathification policy that the U.S. executed in Baghdad thereafter was the kiss of death for the Iraqi state that we knew since 1958. In more than one way, dissolving the Iraqi army was a recipe for the rise of sectarian militias on all sides of the Iraqi spectrum: Shiite, Kurdish and Sunni. Back then, the debaathification fueled a Sunni insurgency championed by al-Qaeda’s Abu Musaab Zarqawi until 2006, and later reemerged more ferociously after the U.S. withdrawal in 2011 in the form of ISIS. In that sense, the erosion of inclusive governance under Nouri al-Maliki played directly into ISIS’ hands, helping the group recruit disaffected Sunnis and reverse the Sahwa strategy leading up to the fall of Mosul last June.

In Syria, the end of the Sykes-Picot structure started unfolding when the Assad regime prioritized its survival at the expense of the country’s unity and sovereignty in 2011. Today, after the failure of both Geneva 1 and 2, militias and more self-autonomous regions have mushroomed Syria. Even the regime is no longer fighting to restore full control over the country, and the old borders that the British and French drew have become irrelevant. Border crossings in every corner of the country are being challenged daily by the rebels, Kurdish fighters, Hezbollah, Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS.

The breakup of the Syrian and the Iraqi states is happening before our own eyes, and ISIS is just one symptom of the new post-Sykes-Picot configuration. While the international community still emphasizes publicly the unity of Iraq and Syria, in reality everyone is quickly adjusting to the new order. Arming of Kurdish groups, investing in Shiite, Sunni and Druze militias, is happening at a faster pace than any political solution. There is a realization in Western capitals that the nation states in Baghdad and Damascus are breaking up and it is too costly for Washington and its allies to save them. Hence, an adjustment to contain the collapse and the spillover, defines the U.S. policy today in approaching ISIS and those crises.

ISIS will last for a while

ISIS will last for a while

It is only by understanding the disintegration of Iraq and Syria that the rise of ISIS can be put in perspective in the short and the medium term. If it were not for the political woes of Iraq since the invasion in 2003, and later the bloodletting in Syria which refueled the group, ISIS would not be at the center stage of the regional conversation and its “Caliphate” wouldn’t be a brutal milestone in Middle East trajectory a year later.

As those same political woes generated by Sunni disenfranchisement continue, and absent of a real military plan to confront it, ISIS prospects look steady and long-term across its territory. While the borders of ISIS could change as the group faces losses against Kurdish militias, and gains against the Iraqi army, there are no indications that imminent defeat or destruction will befall the “Caliphate”. Neither the U.S. nor its coalition partners are willing to invest in a real ground operation that would uproot ISIS, nor are the governments in Baghdad and Damascus the least willing or able to construct political solutions that would offer alternatives to ISIS.

Despite its brutality against Muslims before anyone else, ISIS has lot of factors in its favor from Ramadi to Palmyra. The political solution in Syria is a corpse, and the new chatter on a Russian-U.S. proposal is -like the old – just another facade to distract from a gloomy reality that the country is crumbling with no interest in Washington to resurrect it. Investing in militias that would fight ISIS in Syria is the most realistic scenario expected from the U.S. going forward and the battles of Kobane and Tal Abyad offer a practical example of such vision. In Iraq, the government of Haider al-Abadi is succumbing to a new power structure where Iranian funded militias have larger say than the Iraqi army in the political and military direction of Baghdad and the anti-ISIS battle. Abadi despite his moderate public rhetoric and promises of inclusion, has not been able to establish a national guard force that would enlist the Anbar tribes to fight ISIS.

Against such backdrop, the first anniversary of ISIS’ Caliphate is one that reasserts the irrelevance of the Sykes-Picot borders in Iraq and Syria. As these lines are redrawn, and military alliances are reconfigured, ISIS as a phenomenon will persist for a while, absent of inclusive political structures and real military planning to confront it.

Al Arabiya

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.