Iran is not expected to normalize relations with the United States even if Tehran reaches agreement with world powers on its nuclear program, officials and analysts said.

Iran is not expected to normalize relations with the United States even if Tehran reaches agreement with world powers on its nuclear program, officials and analysts said.

The United States, Britain, France, Germany, Russia and China are trying to reach a deal with Iran aimed at stopping Tehran being able to develop a nuclear bomb in exchange for an easing of sanctions that are crippling its economy.

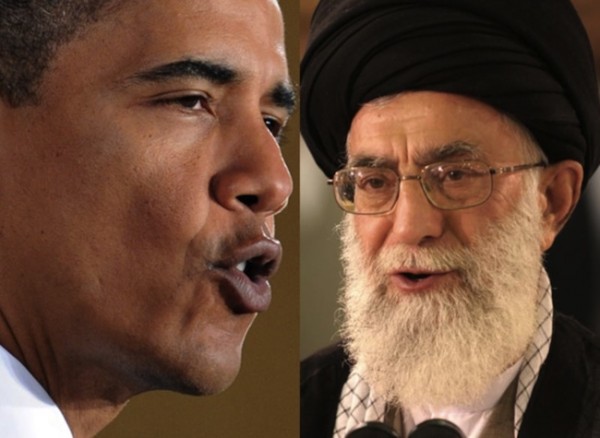

Loyalists of supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, drawn from among Islamists and Revolutionary Guards who fear continued economic hardship might cause the collapse of the establishment, have agreed to back President Hassan Rouhani’s pragmatic readiness to negotiate a nuclear deal, Iranian officials said.

“But it will not go beyond that and he (Khamenei) will not agree with normalizing ties with America,” said an official, who spoke in condition of anonymity.

“You cannot erase decades of hostility with a deal. We should wait and see, and Americans need to gain Iran’s trust. Ties with America is still a taboo in Iran.”

Tension between the hardline and pragmatic camps over the nuclear talks has reduced in recent months since Khamenei publicly backed the negotiations.

However, Khamenei has continued to give speeches larded with denunciations of Iran’s “enemies” and “the Great Satan”, words aimed at reassuring hardliners for whom anti-American sentiment has always been central to Iran’s Islamic revolution.

Khamenei, whose hostility towards the Washington holds together Iran’s faction-ridden leadership, remains deeply suspicious of U.S. intentions.

But despite disagreement over Iran-U.S. ties, Iranian leaders, whether hardliners or pragmatists, agree that a nuclear deal will help Iran to rebuild its economy.

Relations with Washington were severed after Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution and enmity to the United States has always been a rallying point for hardliners in Iran.

“As long as Khamenei remains Supreme Leader the chances of normalizing U.S.-Iran relations are very low. Rapprochement with the U.S. arguably poses a greater existential threat to Khamenei than continued conflict,” said Karim Sadjadpour, an Iran expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington.

“After three decades of propagating a culture of defiance against the U.S., it will be curious to see whether and how Khamenei spins a nuclear compromise as an act of resistance, not compromise.”

“There are different views among top officials over the normalization of ties with America when the nuclear dispute is resolved. But the Supreme Leader is against it,” said another Iranian official. “And he is the decision-maker.”

Economically, the stakes are high, meaning that while Khamenei needs to keep the hardliners on side, a nuclear deal is a price he seems willing to pay.

Iran is under U.N., U.S. and European Union sanctions for refusing to heed U.N. Security Council demands that it halt all enrichment- and plutonium-related work at its nuclear sites.

The sanctions have severely damaged the Iranian economy, halving oil exports to just over 1 million barrels per day since 2012 while the country is also struggling with a sharp decline in international crude prices.

Rouhani, who dealt with Washington during the sale of arms to Iran during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, has broken the taboo of engaging publicly with the United States. But rapprochement will only go so far.

“Despite all the meetings over the nuclear issue, Iran and America both need an enemy and I do not think ties will be normalized after the deal. But they will keep the communication channel open,” said Tehran-based political analyst Saeed Leylaz.

“Iranian leadership needs chants of Death to America to keep hardliners united. And opening an American embassy in Tehran is not going to happen, at least in the near future.”

Khamenei has been adept at ensuring that no group, even the hardliners, becomes powerful enough to challenge his authority, so if Rouhani secures a nuclear deal, it is likely to mean he is kept on a shorter leash when it comes to internal reforms and human rights, analysts say.

“The prospect of a triumphant Rouhani and an ascendant centrist faction could exacerbate the conservatives’ fears of losing too much political ground and provoke them to thwart Rouhani’s economic, social, and political reforms, should he pursue them,” said Ali Vaez, an expert at the International Crisis Group.

“Khamenei’s ruling style is to wield power without accountability … In that context he needs a Rouhani who is weak enough not to pose a threat, but seemingly powerful enough to absorb popular blame for any shortcoming,” said Carnegie’s Sadjadpour.

Rouhani is not the first president with a reform agenda to serve under Khamenei. Greater social and political freedom was initially allowed under Mohammad Khatami, but later Khamenei saw it as a threat.

Khatami’s support was crucial in Rouhani’s election win, but the president can expect trouble ahead.

“To prevent Rouhani gaining more popularity and power inside Iran, the pressure on the reformist camp has increased and will continue to increase,” said Leylaz, the political analyst.

COMMON INTERESTS

But even if Khamenei maintains a hard line, Tehran and Washington have common interests and threats across the Middle East. They have cooperated tactically in the past, including when Iran helped the United States counter al Qaeda in Afghanistan and Islamic State in Iraq.

“Iran and the United States have some common enemies and also a clash of interests in the region. Therefore, they will continue to share intelligence and keep this back channel open,” said Leylaz.

But on the other side of the equation, Iran’s rival Saudi Arabia fears a nuclear deal might embolden Tehran to tighten its grip in the Middle East and step up its efforts to dominate Arab countries such as Lebanon, Syria and Iraq.

And like Washington’s other Middle Eastern ally, Israel, Saudi Arabia fears that PresidentBarack Obama has in the process allowed their mutual enemy to gain the upper hand.

Reuters

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.