The United States is considering letting Tehran run hundreds of centrifuges at a once-secret, fortified underground bunker in exchange for limits on centrifuge work and research and development at other sites, officials have told The Associated Press.

The trade-off would allow Iran to run several hundred of the devices at its Fordow facility, although the Iranians would not be allowed to do work that could lead to an atomic bomb and the site would be subject to international inspections, according to Western officials familiar with details of negotiations now underway. In return, Iran would be required to scale back the number of centrifuges it runs at its Natanz facility and accept other restrictions on nuclear-related work.

Instead of uranium, which can be enriched to be the fissile core of a nuclear weapon, any centrifuges permitted at Fordow would be fed elements such as zinc, xenon or germanium for separating out isotopes used in medicine, industry or science, the officials said. The number of centrifuges would not be enough to produce the amount of uranium needed to produce a weapon within a year — the minimum time-frame that Washington and its negotiating partners demand.

The officials spoke only on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss details of the sensitive negotiations as the latest round of talks began between U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif. The negotiators are racing to meet an end-of-March deadline to reach an outline of an agreement that would grant Iran relief from international sanctions in exchange for curbing its nuclear program. The deadline for a final agreement is June 30.

One senior U.S. official declined to comment on the specific proposal but said the goal since the beginning of the talks has been “to have Fordo converted so it’s not being used to enrich uranium.” That official would not say more.

The officials stressed that the potential compromise on Fordow is just one of several options on a menu of highly technical equations being discussed in the talks. All of the options are designed to keep Iran at least a year away from producing an atomic weapon for the life of the agreement, which will run for at least 10 years. U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz has joined the last several rounds as the negotiations have gotten more technical.

Experts say the compromise for Fordow could still be problematic. They note it would allow Iran to keep intact technology that could be quickly repurposed for uranium enrichment at a sensitive facility that the U.S. and its allies originally wanted stripped of all such machines — centrifuges that can spin uranium gas into uses ranging from reactor fuel to weapons-grade material.

And the issue of inspector access and verification is key. Iran has resisted “snap inspections” in the past. Even as the nuclear talks have made progress, Iran has yet to satisfy questions about its past possible nuclear-related military activity. The fact that questions about such activity, known as Possible Military Dimensions, or PMDs, remain unresolved is a serious concern for the U.N. atomic watchdog.

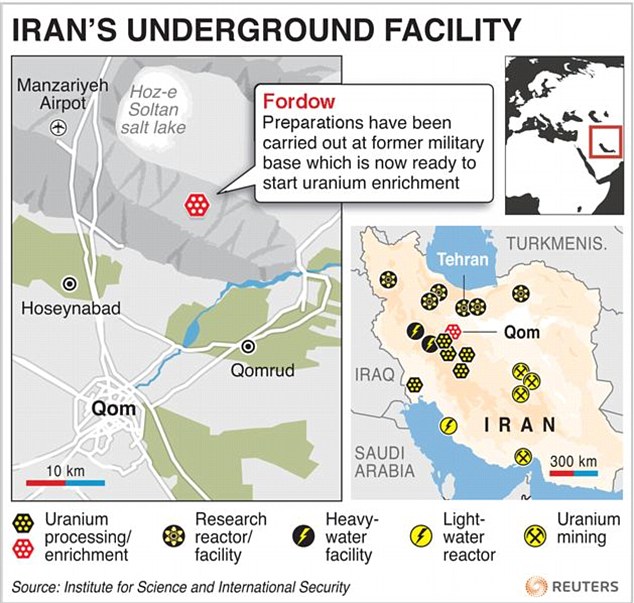

In addition, the site at Fordow is a particular concern because it is hardened and dug deeply into a mountainside making it resistant — possibly impervious — to air attack. Such an attack is an option that neither Israel nor the U.S. has ruled out in case the talks fail.

And while too few to be used for proliferation by themselves, even a few hundred extra centrifuges at Fordow would be a concern when looked at in the context of total numbers.

As negotiations stand, the number of centrifuges would grow to more than 6,000, when the other site is included. Olli Heinonen, who was in charge of the Iran nuclear file as a deputy director general of the U.N’s International Atomic Energy Agency until 2010, says even 6,000 operating centrifuges would be “a big number.”

Asked of the significance of hundreds more at Fordow, he said, “Every machine counts.”

Iran reported the site to the IAEA six years ago in what Washington says was an attempt to pre-empt President Barack Obama and the prime ministers of Britain and France going public with its existence a few days later. Tehran later used the site to enrich uranium to a level just a technical step away from weapons-grade until late 2013, when it froze its nuclear program under a temporary arrangement that remains in effect as the sides negotiate.

Twice extended, the negotiations have turned into a U.S.-Iran tug-of-war over how many of the machines Iran would be allowed to operate since the talks resumed over two years ago. Tehran denies nuclear weapons ambitions, saying it wants to enrich only for energy, scientific and medical purposes.

Washington has taken the main negotiating role with Tehran in talks that formally remain between Iran and six world powers, and officials told the AP at last week’s round that the two sides were zeroing in on a cap of 6,000 centrifuges at Natanz, Iran’s main enrichment site.

That’s fewer than the nearly 10,000 Tehran now runs at Natanz, yet substantially more than the 500 to 1,500 that Washington originally wanted as a ceiling. Only a year ago, U.S. officials floated 4,000 as a possible compromise.

One of the officials said discussions focus on an extra 480 centrifuges at Fordow. That would potentially bring the total number of machines to close to 6,500.

David Albright of Washington’s Institute for Security and International Security says a few hundred centrifuges operated by the Iranians would not be a huge threat — if they were anywhere else but the sensitive Fordow site.

Beyond its symbolic significance, “it keeps the infrastructure in place and keeps a leg up, if they want to restart (uranium) enrichment operations,” said Albright, who is a go-to person on the Iran nuclear issue for the U.S. government.

Associated Press/ My way

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.