Jerusalem’s Mahane Yehuda market has long been a stronghold of Likud, the rightwing party of Israel’s prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu. It is a bustling place of stalls stacked with wet fish, spices, nuts and tubs of olives.

Last week Netanyahu visited the market’s lanes on an election campaign stop that was – bizarrely – unannounced even to the local media.

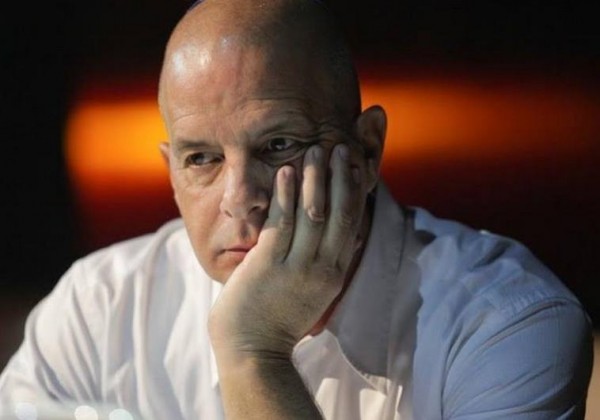

One market figure who greeted Netanyahu in the past was, however, absent from the tour this time: Yaron Tzidkiyahu, the market’s “pickle king”, who runs two deli stands.

A Likud party activist for 40 years, including as a member of its central committee, Tzidkiyahu had decided only a few days before that this year he was not voting for Netanyahu. This time he would vote for Netanyahu’s rightwing rival, Avigdor Lieberman.

His decision to defect – which surprised even his family when he announced it at a Shabbat dinner – was not an isolated incident in a campaign which has been overtaken by the strong whiff of panic emanating not only from Likud but from Netanyahu himself. It is an anxiety driven by the knowledge that they are losing stalwart supporters like the pickle king.

On Thursday Tzidkiyahu explained why he had left the party. “I grew up in Likud,” he said. “But this time I have decided to back Avigdor Lieberman. It’s not that I don’t respect Bibi,” he added, using the Israeli prime minister’s nickname, “but he has disappointed people by not doing more about the social and economic issues facing Israel.

“And in this campaign Bibi made all the possible mistakes. He ignored the issues people cared about and only spoke about security – about Iran, Hamas and Isis. He’s great on security issues, but there are other things Israelis are concerned with.”

As we spoke, a regular customer, Moti Freed, a pensioner, approached him. “I hear you’re voting for Lieberman,” said Freed, who later declared that his own preference is for a centre-left party. “You’re crazy!”

Tzidkiyahu said he knows other disappointed Likud voters. “There are many and most will vote for another party. Not the left but Lieberman, or someone like Moshe Kahlon [a former Likud minister who has launched his own party].

“Netanyahu has done everything wrong,” he said, adding that there had been efforts to persuade him to change his mind. “He hasn’t allowed other people to have their say. The only one allowed near the microphone is him.”

In the last few days, confronted with the increasing lead that is being opened up by his main rival, the Labour party’s Yitzhak Herzog, Netanyahu has seemed increasingly desperate.

Equally worrying for his campaign, the previously wide gap between Netanyahu and Herzog on the question of who voters believe to be most suitable to lead Israel had, by Friday, closed to a narrow margin.

“Don’t stay at home and don’t waste your votes,” Netanyahu pleaded with voters on local radio last week. “I will not be elected if the gap is not closed, and there is a real danger that Tzipi [Livni] and Bougie [Herzog] will form the next government.” Herzog and Livni are the joint leaders of the centre-left Zionist Union alliance that is competing in the election.

And in the last days of the campaign the message from Likud has been to remind Israelis of 1996, when voters stayed faithful at a similar moment of truth and Netanyahu was elected to office for the first time.

His message, as spelled out in a Q&A with voters on his Facebook page on Friday, is that Israel stands at a “critical juncture between two ways”, warning that his rivals “will make concessions all along the way – the achievements we have gained while preserving the vital interests of the country”.

The reality – as Netanyahu understands as well as anybody else – is that Tuesday’s vote will be a referendum on his leadership and personality. Even if he can find a way to build another coalition, possibly with fewer seats than Herzog’s party – which can happen in Israel’s political system – the politician who has been a key figure for a quarter of a century will look like damaged goods.

Most Israelis, as polls have consistently made clear, would rather he was gone. (According to one poll published on Friday, 72% of Israelis want change.) As well as his perceived shortcomings on the domestic front, he has brought Israel’s key relationship – with Washington – to a historic low point and increased the country’s isolation on the international stage.

In large part Netanyahu’s electoral problems are his own doing: he has provided an object lesson in how not to conduct a political campaign. Unwilling to debate with his opponents on television or draw up an electoral manifesto, his biggest setpiece political event was not even in Israel but in Washington, where he addressed the Israeli lobby group Aipac (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee) and the United States Congress.

Prior to the last-minute media blitz last week that saw him take to television, print and Facebook, he has largely dodged those Israeli journalists that he has accused of being part of a hostile conspiracy to unseat him from office, and has kept even party activists at an arm’s length. The result has been a Netanyahu campaign that has seemed remote and largely devoid of substance, except on the question of Iran’s nuclear programme and Israel’s security, neither of which, polls have consistently suggested, are the principal concerns of an electorate far more preoccupied with social and economic issues.

His belated and grudging response on key points – given at the end of the week – was not to offer concrete proposals but to promise that he will do better next time, as he finally admitted that the cost of living and skyrocketing house prices “were not dealt with effectively”.

And it has not only been his opposition rivals who have gone on the attack. In the last two weeks anonymous Likud officials have not been backward in coming forward to denounce their own party leader’s campaign, most recently in Haaretzon Friday. “Even if we manage to form the next government, this campaign was a colossal failure,” bemoaned a senior official quoted by the paper. “Netanyahu is primarily responsible.”

Those anonymous voices were joined on Friday by several former senior Likud figures who made no bones about making public their opposition to Netanyahu. One, Dan Meridor, told the Hebrew newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth: “Bibi is the biggest phoney in the world. He may talk sweet, especially in English, but if psychologists or other experts analyse his speeches, it is clear they are just hot air.”

What seems extraordinary in hindsight is that when Netanyahu called snap elections in early December after firing justice minister Tzipi Livni and finance minister Yair Lapid, senior Likud officials believed that he had no serious rival and would steal a march on figures such as Herzog and Lapid in the election preparations. It was a certainty that was acknowledged even on the left which, for the first half of the campaign, subscribed to a fatalistic certainty that Netanyahu would be re-elected.

That mood was prevalent enough to draw mockery from Israel’s leading satirical television show Eretz Nehederet which has depicted Netanyahu as a figure cursed as a child to be Israeli prime minister for eternity. His only chance to break the spell, it suggested, was to become its worst-ever leader.

His speech to the US Congress too, officials have intimated in recent interviews, was supposed to be a master stroke that would clinch the deal and send him cruising to election victory, even at the risk of the damage that it has done to relations with President Barack Obama’s administration. Except that something else happened.

What little bounce he did get from the polls in the immediate aftermath of the speech only brought him level with Herzog, and he has slipped in the intervening period. If the public opinion polls have made for increasingly grim reading for Likud, leaks of internal polling, conducted both by Likud and the Zionist Union, have spread even more alarm among the party faithful, suggesting an even bigger deficit for Netanyahu’s party and reflecting the fact that Likud has underperformed in the polls on election day in the previous two campaigns.

Yaron Tzidkiyahu’s disillusionment is echoed by other accounts that have been bleeding out of the Netanyahu campaign, including the dismal picture painted byHaaretz’s Yossi Verter of a recent meeting of senior Likud figures in Tel Aviv.

By Verter’s account, “dozens of leading Likud figures, mayors, deputy mayors and heads of party branches received urgent phone calls asking them to show up the following morning at a hall in Yehud, east of Tel Aviv, for a meeting with their party head. Not everyone, however, was prepared to ditch other plans.

“Those who did show up encountered a leader under pressure. They got the impression from Netanyahu that the situation vis-à-vis Likud was far from rosy … ‘People want to vote Likud’ they told each other, ‘but don’t feel like voting for Bibi again.’”

All of which has converged to produce an election that is still too close to call. And despite the increasing optimism in Herzog’s camp and others in the “anyone-but-Bibi” tendency, Netanyahu – for all his problems – is not yet finally down and out.

Instead, even if he secures fewer votes than Herzog’s party, the peculiarities of Israel’s complex system of coalition building mean that Netanyahu could still return to the prime minister’s house on Balfour Street.

In the end it will be Israel’s president, Reuven Rivlin – known to Israelis as “Ruby” – who must decide on the basis of the results and the recommendations of the individual parties who to approach first to invite to form a coalition – assuming he does not insist the parties’ leaders negotiate a national unity government. And despite being a member of Likud himself, Rivlin is reported still to be raw over the efforts made by Netanyahu last year to block him from becoming Israel’s president.

The Jerusalem Post’s chief political correspondent, Gil Hoffman, told the Observerhe believes that the next prime minister is likely to be defined as much by Rivlin’s decisions as by the result.

“I have been saying this for a long time, but I see this election as being about Ruby, Ruby and nothing but Ruby,” he said.

Hoffman pointed out that Netanyahu has previously governed with only 19 party seats, but is unconvinced that the Likud leader could scrape by again in a coalition with such a low haul, and he suspects Rivlin would insist that he join a national unity government. That would be seen as a defeat for Netanyahu as much as a Herzog-led coalition.

And with the last polls published on Friday, Israel will now have to wait until Tuesday at 10pm, when the first exit polls come out, to see whether it is the end of “King Bibi” or whether he survives to lead Israel for another term.

BIBI’S RISE TO POWER

Born on 21 October 1949, Netanyahu grew up in the US after his father Benzion, a history professor, was considered so rightwing in the Labour-dominated Israel of the time that he was forced to leave.

Before attending the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he served in an elite Israeli army commando unit, rising to the rank of captain, and was wounded in combat.

He was deeply affected by the death of his elder brother Yonatan, who was killed leading the 1976 Israeli commando raid to free the passengers of an Air France plane hijacked by Palestinians to Entebbe, Uganda.

His career took off when he was posted to Israel’s embassy in Washington and was later made ambassador to the UN.

When he was first elected in 1996, Netanyahu was Israel’s youngest-ever prime minister. If re-elected, he will become the second longest-serving after the country’s founding father, David Ben-Gurion.

He was defeated in 1999 by the Labour leader Ehud Barak.

Under Barak’s successor, Ariel Sharon, he served as foreign minister and finance minister.

In late 2005, he took over as leader of the rightwing Likud party after Sharon left to found the centrist Kadima.

He led Likud to a humiliating defeat in 2006, but the party bounced back three years later.

After Likud came out on top in the 2013 election, Netanyahu fought to form a coalition, but it failed to become established, and he took the gamble last December of calling the election two years early.

Netanyahu and his third wife Sara have two sons and he has a daughter from his first marriage.

The Guardian

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.