Two Irish filmmakers spent five years documenting the daily life of a village in the Golan Heights, writes Ellie O’Byrne

Two Irish filmmakers spent five years documenting the daily life of a village in the Golan Heights, writes Ellie O’Byrne

IT’S not your typical wedding. The bride is tear-streaked and dishevelled as the groom ushers her forward across a manned checkpoint. She turns repeatedly for what may well be her last glimpse of her aging parents as her new family gather round, encouraging her on as she steps hesitantly towards her future.

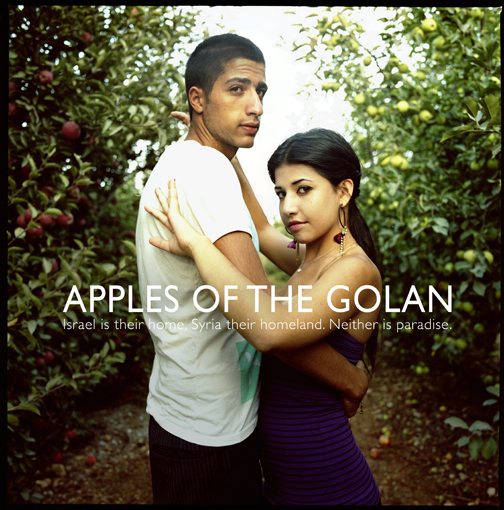

For the Druze community of Majdal Shams, the subject of Irish filmmakers Jill Beardsworth and Keith Walsh’s documentary, Apples of The Golan, this scene is all too familiar.

For 48 years, since Israel seized the Golan Heights during the Six-Day War, this community has been holding out; one of five remaining Arab villages in the occupied territory, they hope for reunion with Syria, which most consider their homeland, and also struggle with bitter divisions within their own ranks.

A minefield fenced in barbed wire divides Syria and Israel on the outskirts of Majdal Shams; Syria is visible, but unreachable.

Families divided by the border are cut off, and shout messages across the minefield, which is known locally as the ‘Valley of Tears’. The Druze are an ethnic group with their own religion.

The film’s title references their historic livelihood as apple growers, still a major source of income.

Apples of The Golan was five years in the making for Galway duo, Beardsworth and Walsh, who spent a year in total in Majdal Shams. The film covers a four-year period before the Syrian conflict became civil war.

“We would generally go in September, while the apple harvest was on, because that was when most of the activity was happening,” says Beardsworth.

“That was one reason it took so long. We also didn’t have fluent Arabic when we started to make it, so there was time involved in getting translations back and figuring out people’s stories.”

The film explores the effects of occupation on its subjects, rather than provide a political narrative.

Often, the subjects are left to speak for themselves and, occasionally, the effect is oppressive — the older generation clinging to their Syrian identity, repeating endlessly their message of loyalty to Syrian president Bashar Al Assad, or ‘The Beloved’. Younger generations seem disaffected and cynical.

They say they belong neither to Israel nor to their parents’ memories of Syria. Hip hop, skateboarding, and salsa dancing are creative outlets.

For Beardsworth and Walsh, one challenge was to gain the trust of the insular Druze community. “It’s a secretive religion, in a place that’s infiltrated by spies, both on the Israeli side and the Syrian side,” Walsh says.

There are even rumours that an Irish spy had previously stayed in the village. “Whether that’s true or not, that’s what locals believed and that certainly didn’t help us.”

That Beardsworth and Walsh are a couple humanised them in the eyes of the villagers and, over time, locals came to recognise the commitment they had made to telling their story.

The duo provide a balanced overview of the situation, and the film remains descriptive rather than prescriptive. Given the friendships and bonds they formed over five years, was it difficult to remain detached?

“We went to weddings, funerals, played with their babies. I was only saying, the other day, that I went to more weddings in the Golan Heights than I’ve ever been to here,” Walsh says. “But we had to preserve our position, too. Each family has their political position, so we had to be very careful not to get side-tracked.”

One tactic was to review and edit their footage in Ireland, which Jill said allowed them to preserve their emotional distance. With 250 hours of raw footage, the editing alone took nearly a year.

“It was hard editing,” Beardsworth says. “We had to distil the story down, until it was coherent, beautiful and faithful to the story that we saw over there.”

Walsh agrees: “One of our biggest challenges was not to get bogged down in something too investigative or didactic, but to try to bring out the visual element. I felt that challenge was more in the edit than in the shooting.”

Shot by Walsh, with Beardsworth recording the sound, and both directing and editing, highlights include a couple salsa dancing in an orchard, the last remaining shepherd singing on his parched hillside, and the apples, pared down and divested of political significance.

A tapestry of poignant scenes is woven; balloons drifting across the Valley of Tears towards Syria, or trapped fish flopping in a pail, metaphors for the Druze community’s situation.

It’s difficult not to be affected by the drama, heartache and sporadic violence of the villagers’ lives. In one scene, Syrian bride Layla Saffadi hears of her father’s death and drives to the checkpoint in the futile hope of being allowed through to see his body.

In 2011, while Walsh and Beardsworth were in Ireland, refugees from Palestine and Syria tried to swarm the fence at the border between Syria and Israel. The Israeli army killed as many as 23 of them.

The filmmakers’ local production manager, Hamid Awidat, recorded the events and the resulting footage appears in the film.

In recent times, the situation in the Golan has been exacerbated by the Syrian civil war. The Syrian side of the border is now controlled by rebel factions — including an Al-Qaeda affiliate encountered recently by an Irish peacekeeping contingent —fighting Assad’s army and the people of Majdal Shams are even more isolated. They are no longer able to even exchange apples and brides with Syria.

Their future is more perilous now then it was when Apples of The Golan was filmed.

“There’s a cold civil war going on in the village at the moment, with some people supporting Al Assad and some supporting the rebels,” says Walsh.

“The village was very united for 40 years of occupation, but when I was there last there were brothers who wouldn’t sit at the same table with each other.”

Beardsworth is fearful of the effects of such division. “Family there is very strong, much stronger than here, and to think that that’s being shattered or broken, I find it terribly sad,” she says. “We had an email from Hamid this morning and he finished it by saying, ‘It’s hell here’.”

Wildcard Distribution had announced that the Irish documentary Apples of the Golan will open at the IFI Cinemas on Friday, 16th January 2015.

Irish Examiner

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.