By: Michael Crowley

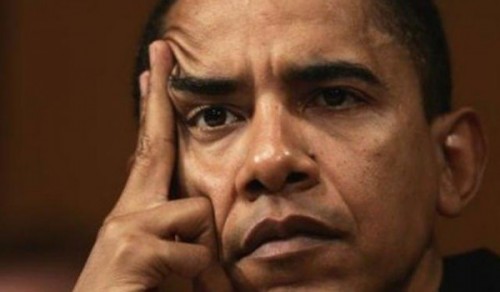

For the better part of three years, President Barack Obama kept a wary distance from Syria’s civil war. He had little appetite for getting entangled in another Middle East conflict, and knew the public agreed with him, while also doubting that the U.S. could hope to control the bloody chaos there. In 2012, he resisted pressure from Hillary Clinton, Leon Panetta and David Petraeus to provide the rebels with more support. Even after Syrian President Bashar Assad murdered civilians with nerve gas last year, Obama backed away from threatened air strikes and approved only limited arms transfers and CIA training of moderate fighters on a small scale. His ambassador to Syria resigned in February, saying he could no longer defend Obama’s cautious policy.

Now Obama has dramatically reversed his position. The White House is asking Congress for $500 million to create a Pentagon program to train and arm what it called “appropriately vetted elements of the moderate Syrian armed opposition.”

This is no quick fix. It may not be a fix at all. Obama’s plan will take months to get off the ground, even if Congress agrees to it. But it does amount to a clear admission—you might even call it a concession—by Obama that his Syria policy is not working.

Why the shift now? The short answer is Iraq. The ISIS blitz through northern and western Iraq shows how the festering wound of Syria’s civil war is infecting the wider region. ISIS has drawn manpower, money and momentum from the Syrian civil war, and now controls a large swath of Syrian territory. To prevent it from burning down Iraq, the ISIS fire needs to be squelched in Syria.

Assad can’t do that. He has reached a kind of stalemate with his rebel enemies, and at times has even seemed to be in a de facto truce with ISIS. Obama won’t do it either. For now, military action to tilt the Syrian battlefield is not a live option.

A partial solution could come in the form of moderate Syrian rebels, who don’t subscribe to radical anti-western Islamic dogma, and who don’t want to see ISIS, and similar radical groups, gain power in Syria.

Obama says that full solution to the Syria crisis, and the radicalism it breeds, is a political settlement. The goal is for Assad to step down, making way for a new multisectarian government in his place.”[W]e continue to believe that there is no military solution to this crisis,” national security council spokeswoman Caitlin Hayden said in a June 26 statement.

A stronger Syrian opposition might be able to break the stalemate and pry Assad from his grip on power, Obama’s ex-ambassador to Damascus, Robert Ford, told PBS earlier this month. “We can’t get to a political negotiation until the balance on the ground compels — and I use that word precisely—compels Assad … to negotiate a political deal,” Ford said.

But here’s where things get complicated: Do we still want Assad gone? ISIS’s frightening offensive in Iraq has made the tyrannical opthamologist seem like a potentially useful ally. Loathsome as Assad may be, it’s hard to argue that his defeat is more important than that of ISIS—which, unlike Assad, aspires to start a regional civil war with Shi’ites and even launch terror attacks against western targets. Assad, whose jets bombed ISIS positions along Iraq’s border this week, is the enemy of our enemy. Does that make him our friend? Some foreign policy thinkers suggest so, calling for a short-term U.S. alliance with in the anti-ISIS fight.

Obama’s not there yet. He still wants Assad gone. He just doesn’t want him toppled by ISIS.

It’s not exactly a simple plan. And it will unfold slowly. If Congress approves Obama’s plan, it will be months longer before a Pentagon training program gets underway—and more time still before it forges enough skilled fighters to shape the Syrian conflict.

What’s clear is that Obama understands the status quo in Syria is a disaster, on that is creating what the recently-departed United Nations special envoy, Lakhdar Brahimi, called a “failed state” prone to “blow up” the wider region.

And so Obama may be admitting he’s wrong. After months of arguing that taking serious action in Syria is too risky, Obama is signaling that the consequences of inaction— now unfolding across northern and western Iraq—are too dangerous to tolerate.

Time

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.