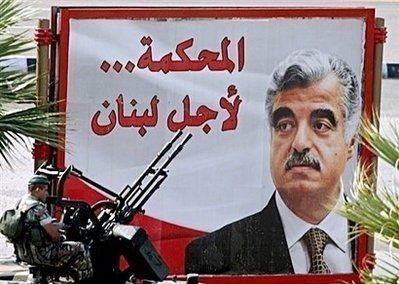

Nine years after the assassination of Lebanese statesman Rafik al-Hariri, the trial of four men accused of his killing opens on Thursday. But the defendants are on the run, bombers are back on Beirut streets and a new era of justice which the trial was meant to introduce to Lebanon remains elusive.

Nine years after the assassination of Lebanese statesman Rafik al-Hariri, the trial of four men accused of his killing opens on Thursday. But the defendants are on the run, bombers are back on Beirut streets and a new era of justice which the trial was meant to introduce to Lebanon remains elusive.

Hariri and 21 other people were killed on the Beirut seafront in February 2005, the deadliest of a series of attacks against critics of Syria’s military dominance in Lebanon.

His killing triggered huge public protest and led to the establishment of the U.N.-backed Special Tribunal for Lebanon, a court near The Hague where prosecution lawyers will set out the case against the four absent defendants on Thursday before a panel of Lebanese and international judges.

Hariri’s Western supporters hailed the tribunal as a chance to close a long chapter of impunity in Lebanon, where bombers and assassins have operated since the 1975-1990 civil war with little prospect of facing justice in court.

But the bomb which killed the billionaire former premier also drove a wedge between Hariri’s Sunni Muslim community and Lebanese Shi’ites loyal to Syrian-backed Hezbollah, whose members now stand accused the killing.

That rift has been further poisoned by differences over Syria’s civil war, which has drawn Lebanese Sunni and Shi’ite fighters onto opposing sides and has spilled over into deadly sectarian attacks in Lebanon’s main cities.

Late last month, just three weeks before the trial’s opening, a close adviser to Hariri’s son was killed by a car bomb just a few hundred meters from the 2005 attack. Days later a suicide bomber struck in Hezbollah’s south Beirut stronghold.

“After almost nine years, it seems like things are going worse, even worse than at that time,” said Nara Hawi, daughter of a communist opponent of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad who was killed in July 2005, five months after Hariri.

Her father, George Hawi, died when a bomb exploded under the passenger seat of his Mercedes. His killing is one of three other cases which also fall under the tribunal’s mandate but Nara Hawi said she had no idea how the investigation was going.

“Concerning the tribunal, it is more hope than expectation,” she said.

Lebanese President Michel Suleiman described the trial as “a step towards accountability and a lesson to those who plot to commit more crimes”.

TWO TONNE BOMB

According to prosecution documents and investigators’ reports the February 14, 2005 attack on Hariri was a meticulously planned and devastating strike.

The bomb, in a Mitsubishi van filled with the equivalent of 2.5 tonnes of high explosive, was detonated by a still unidentified suicide bomber and ripped through the busy approach to the Mediterranean corniche, they say. Twenty-two people died and another 226 people were wounded.

Hariri is buried in Beirut’s Martyr’s Square, not far from the site of the explosion and next to the huge, blue-domed Mohammed Al-Amin mosque which he helped construct.

One million people, a quarter of Lebanon’s population, protested in Beirut against the killing. The pressure on Syria, whose officials were implicated in early U.N. investigations, led it to pull troops out of its smaller neighbor, ending a military presence which lasted 29 years.

Investigators eventually focused on a network of mobile phones which prosecutors say were used by Hariri’s killers to plan and carry out the bombing. Much of the prosecution case released so far rests on records of phones it says were used by the four Hezbollah defendants and their accomplices.

The four indicted men include Mustafa Amine Badreddine, 52, a senior Hezbollah figure and brother-in-law of slain Hezbollah commander Imad Moughniyeh. The others are Salim Jamil Ayyash, 50, Hussein Hassan Oneissi, 39, and Assad Hassan Sabra, 37.

But Lebanon has failed to track any of them down in the three years since they were indicted and they will be tried in absentia, defended by court-appointed lawyers.

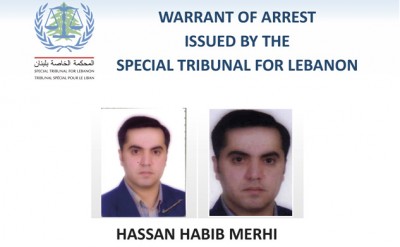

A fifth suspect, Hassan Merhi, was indicted last year, accused of helping prepare the attack and then hiding Hezbollah’s alleged involvement. Judges have not yet granted a prosecution request to merge his case with the others’.

FORMER INTELLIGENCE HQ

The trial will be held in a converted basketball court in the former headquarters of the Dutch intelligence services, a building with its own moat on the outskirts of The Hague, and could run for years.

Other complex international trials, like that of the former Liberian President Charles Taylor which was held in the same room, lasted three and a half years.

Hezbollah, which denies any role in the killing, has refused to cooperate with the tribunal and threatened violence against anyone who tried to detain the suspects.

“Any hand that touches them will be cut off,” the organization’s leader, Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, warned in 2010, as the tribunal was preparing to name the four men.

The powerful Shi’ite militia and political group says the tribunal is a tool of Israel, with which Hezbollah fought a 34-day war in 2006, and that Israel has penetrated Lebanon’s telecommunications network to fabricate a case against it.

Perceived missteps during the investigation, including testimony from witnesses who later recanted and the prolonged detention without charge of four pro-Syrian security officials in Lebanon, also provided ammunition to the tribunal’s critics and ensured it remained a politically charged issue.

Three years ago when tension over the imminent indictments peaked, Hezbollah toppled a national unity government led by Hariri’s son, Saad al-Hariri, after he refused to cut Lebanon’s ties with the tribunal – which is 49 percent funded by Beirut.

Shortly after his government was brought down, and once the uprising in Syria erupted in early 2011, Hariri left Lebanon, fearing for his safety as sectarian violence escalated.

He has remained in exile between France and Saudi Arabia but is due to travel to the court in Leidschendam, outside The Hague, for the start of a trial which his family hopes can deliver at least the truth, if not justice.

“Thursday is a day we waited a long time for,” the slain politician’s nephew, Ahmad Hariri told Reuters. “It’s something new for Lebanon. For 40 years, we haven’t had justice and truth for any assassination.”

Hariri, Secretary-General of the mainly Sunni Muslim Future party, said even if the defendants were never apprehended, a court verdict against them would be damaging to Hezbollah.

Set up by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards 30 years ago, the Shi’ite group had for years enjoyed broad backing as Lebanon’s main resistance force against Israel. But its intervention in Syria and the Hariri allegations have eroded that support base.

“Justice can come in different ways,” Hariri said. “Even if they are not in court… what Hezbollah is doing in Syria and what it has done to its image, that’s also part of the justice that we want.”

BY DOMINIC EVANS

Reuters

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.