BAMAKO, Mali — Khaira Arby, one of Africa’s most celebrated musicians, has performed all over the world, but there is one place she cannot visit: her native city of Timbuktu, a place steeped in history and culture but now ruled by religious extremists.

BAMAKO, Mali — Khaira Arby, one of Africa’s most celebrated musicians, has performed all over the world, but there is one place she cannot visit: her native city of Timbuktu, a place steeped in history and culture but now ruled by religious extremists.

One day, they broke into Arby’s house and destroyed her instruments. Her voice was a threat to Islam, they said, even though one of her most popular songs praised Allah.

“They told my neighbors that if they ever caught me, they would cut my tongue out,” said Arby, sadness etched on her broad face.

Northern Mali, one of the richest reservoirs of music on the continent, is now an artistic wasteland. Hundreds of musicians have fled south to Bamako, the capital, and to other towns and neighboring countries, driven out by hard-liners who have decreed any form of music — save for the tunes set to Koranic verses — as being against their religion.

The exiles describe a shattering of their culture, in which playing music brings lashes with whips, even prison time, and MP3 and cassette players are seized and destroyed.

The exiles describe a shattering of their culture, in which playing music brings lashes with whips, even prison time, and MP3 and cassette players are seized and destroyed.

“We can no longer live like we used to live,” lamented Aminata Wassidie Traore, 36, a singer who fled her village of Dire, near Timbuktu. “The Islamists do not want anyone to sing anymore.”

In Malian society, music anchors every ceremony, from births and circumcisions to weddings and prayers for rains. Village bards known as griots sang traditional songs and poems of the desert, passing down centuries-old tales of empires, heroes and battles, as well as their community’s history. In this manner, memories were preserved from generation to generation, along with ancient African traditions and ways of life.

In current times, lyrics serve as a source of inspiration and learning, a way to pass down morals and values to youths. They have also been used to expose corruption and human rights abuses, and have helped eradicate stigmas and given a voice to the poor.

“In northern Mali, music is like oxygen,” said Baba Salah, one of northern Mali’s most-respected musicians. “Now, we cannot breathe.”

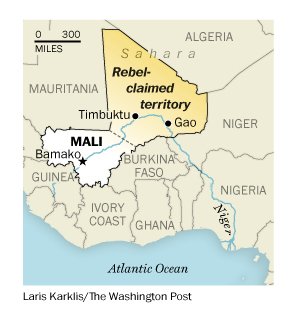

In March, amid a military coup that left the government in disarray, Tuareg rebels who once fought for Libyan autocrat Moammar Gaddafi joined forces with secessionists and Islamists linked to al-Qaeda. They swept through northern Mali, seizing major towns within weeks and effectively splitting this impoverished nation into two. Soon afterward, the Islamists and al-Qaeda militants took control.

They have installed an ultraconservative brand of Islamic law in this moderate Muslim country, reminiscent of Afghanistan’s Taliban and Somalia’s al-Shabab movements. Now, women must wear head-to-toe garments. Smoking, alcohol, videos and any suggestions of Western culture are banned. The new decrees are enforced by public amputations, whippings and executions, prompting more than 400,000 people to flee. The extremists also destroyed tombs and other cultural treasures, saying they were against Islamic principles.

The death of music was inevitable. It is, perhaps, Mali’s strongest link to the West. Musicians such as the late guitarist Ali Farka Toure, the Tuareg-Berber band Tinariwen and singers such as Salif Keita exported their music to the United States and Europe. They often collaborated with Western musicians.

Since 2001, Western artists such as Robert Plant have performed at the Festival of the Desert, outside Timbuktu, transforming Mali into an international artistic and tourist destination. In January, U2 frontman Bono performed with Tinariwen. This February, though, the festival will be held in neighboring Burkina Faso.

The international recognition helped spark a new generation of young artists in the north. Some fused songs in their native Songhai and Tamashek languages with Arabic and French. Others melded traditional rhythms of the desert with rap, hip-hop, reggae, funk and blues. Bands weaved traditional Malian lute and fiddles with electric guitars.

In recent times, the lyrics have addressed social and political issues. In “Waidio,” Arby sings about the plight of women trapped by war. She has also sung about Fulani cattle herders and the hard labor endured by salt miners.

‘Music is against Islam’

Today, in the city of Gao, 39-year-old singer Bintu Aljuma Yatare no longer listens to music on her phone. The Islamists will confiscate it, she said. Five musicians in her band have fled to neighboring Niger; two others are in Bamako. She cannot leave because she has to take care of her aging parents.

Every evening, she risks being sent to prison: She shuts the windows and doors of her house and sings in her native Songhai language. “Sometimes I lie in my bed and hum my songs softly,” she said. “The only way for me to survive this nightmare is through music.”

The other day, she wrote a song about the drivers who take people out of northern Mali to safer pastures.

For reggae musician Alwakilo Toure, his home in Gao was not a sanctuary. He was strumming his guitar when six armed militants barged into his compound. With guns pointed at his head, one Islamist grabbed the guitar and smashed it to bits with his foot. “The guitar was my life,” Toure recalled. “I had nothing else to do.”

Two weeks later, he fled to Bamako.

In a telephone interview, one of the Islamists’ top commanders declared that his fighters would continue to target musicians.

“Music is against Islam,” said Oumar Ould Hamaha, the military leader of the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, one of the three extremist groups controlling the north. “Instead of singing, why don’t they read the Koran? Why don’t they subject themselves to God and pray? We are not only against the musicians in Mali. We are in a struggle against all the musicians of the world.”

Artists without a home

In a cramped apartment in Bamako, about a dozen young artists were recording a song, a fusion of rap and traditional melodies. In one corner, there was a microphone and a computer to mix the tracks. Next to that was a synthesizer.

All the artists were from northern Mali, and none were playing with their own instruments because they had either been burned or shattered by the Islamists. The group included Toure, who was coaching a singer.

But their escape to Bamako is bittersweet.

It has been difficult for the musicians to earn money in the capital. They sing in the languages of the north, but most people in Bamako speak only the southern Bambara language.

“In Bamako, people don’t understand what we sing,” Toure said. “It really hurts us that we can’t perform. Most of us don’t have jobs. Many of us now rely on our relatives for money.”

But even in exile, they have found a way to take a stand against the Islamists.

“We feel like soldiers,” said Kiss Diouara, a 24-year-old rapper. “This is our way to fight our war.”

A few minutes later, he played his group’s most recent creation. The video included a collage of news clips and photos of Islamists destroying ancient mosques and asserting their power. In the video, Diourra raps:

Free the North

We want peace in our land

We want to go back to our homes

Arby understands. For the past eight months, she has lived out of a suitcase.

Arby knows she could easily travel outside Mali for work. Her 2010 album, “Timbuktu Tarab,” was widely acclaimed in the West. She had opportunities to settle in the United States, she said.

But Mali is where she is most inspired, specifically in Timbuktu, she said.

“When I think of Timbuktu, I am lost,” said Arby, wiping a sudden tear that trickled down her cheek. “When I dream of Timbuktu, I wake up. When I think of Timbuktu when I am speaking, I stop speaking. My heart is broken. Timbuktu is everything to me.”

Washington Post

Top photo: In Mali, musicians flee south: Radical Islamists have driven artists from northern Mali, where playing music can bring beatings, and even prison time.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.