Human-rights lawyers are trying to save laws meant to tame violent rulers

The world’s rules-based order is cracking

Rarely have international courts been busier. In The Hague, the International Criminal Court (icc) is considering war-crimes prosecutions against Israeli leaders, including Binyamin Netanyahu, the prime minister, over the conflict in Gaza. It has already issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, for war crimes in Ukraine. The International Court of Justice (icj), also in The Hague, is weighing genocide charges against Israel. In Strasbourg the European Court of Human Rights will hear a request in June for Russia to pay compensation to Ukraine.

The International Court of Justice on February 19, 2024, began hearing arguments from more than 50 states on the legal consequences of Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories [Peter Dejong/AP]

And yet, for all the legal action, rarely have activists seemed gloomier about holding rulers to account for heinous acts. “We are at the gates of hell,” says Agnès Callamard, head of Amnesty International. Countries are destroying international law, built over more than seven decades, in service of “the higher god of military necessity, or geostrategic domination”.

For a time after the cold war the world seemed to move towards an international rules-based order with less conflict, more democracy and open trade. Lawyers looked forward to “universal jurisdiction”—a borderless fight against impunity. Some leaders, such as Slobodan Milosevic of Yugoslavia and Charles Taylor of Liberia, even stood trial for atrocities.

But the order, always imperfect, is breaking up because of intensifying geopolitical rivalries—and efforts to uphold it may only expose its weaknesses. Russia blatantly violated the UN Charter by invading Ukraine. China supports Russia abroad, represses minorities at home and bullies neighbors. America, the chief architect of the system, undermined it with the excesses of its “war on terror”, not least after the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Now critics accuse it of being complicit in atrocities by supporting Israel’s war on terror. Israeli forces have killed tens of thousands of Palestinians in an attempt to destroy Hamas, which killed or kidnapped some 1,1139 Israelis on October 7th.

China and Russia mock the “rules-based international order”, a phrase intoned by President Joe Biden, as a cloak for American dominance. The fuzzy term is similar in meaning to “liberal international order” (a more common phrase that can confuse Americans, for whom “liberal” means left-wing). For Mr Biden it is the antonym of a world governed by brute force. Antony Blinken, his secretary of state, says it is the broad system “of laws, agreements, principles and institutions” to manage relations between states, prevent conflict and uphold human rights. Critics reckon America avoids referring to “international law” so as to preserve its freedom to use force.

Theorists have long debated whether international order is best preserved by a balance of power—such as the “concert of nations” that followed the Napoleonic wars in Europe—or by laws and institutions of the kind America has repeatedly tried to build since the end of the first world war. For Matthew Kroenig of the Atlantic Council, an American think-tank, a liberal global order requires both of these. International rules create stability and prosperity; American power, channelled through its alliances, acts as enforcer in an otherwise anarchic world.

International law has long recognized states’ sovereign immunity, which protects them from legal action in foreign courts. But their use of violence at home or abroad is circumscribed. The UN Charter of 1945 forbids the use of force in international disputes except in self-defense. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 enshrines individual rights to life, liberty and the security of the person. The Geneva Conventions of 1949 regulate war and protect non-combatants. Further conventions ban genocide, torture and more.

chart: the economist

International courts punish breaches. But there is no global policeman to enforce their rulings. Worse, the UN Security Council, the pinnacle of the system—which can authorize force to maintain peace and security—is all but paralyzed by the power of veto held by its five permanent members (see chart).

Coups abound and UN peacekeepers are being ejected from several countries. The consensus to curb nuclear proliferation is eroding, too. In March Russia vetoed a resolution to extend the work of experts who monitor UN sanctions against North Korea’s nuclear-weapons program —a reward for North Korean supplies of weapons to Russia.

Richard Gowan of the International Crisis Group, a think-tank in Brussels, notes that the Security Council can reach tenuous agreement on some crises, for example in Somalia and Haiti. “And it can still agree on sending humanitarian aid, as an alibi for inaction,” he says. But geopolitical rivalry is creating intense battles over who should run the alphabet-soup of UN bodies. Though Russian candidates don’t get far these days, China courts UN members assiduously. It tries to nudge the un away from protecting individual rights and towards upholding the primacy of states.

America increasingly aims to preserve the liberal order through military alliances in Europe and Asia. It regards the G7 as the “steering committee” of the world’s advanced democracies. Some foresee a dual order: a liberal one dominated by America and an illiberal one centered on China.

Even so, human-rights lawyers are trying to preserve the idea of universal rules, and are working through international courts given the un’s impotence. The system has many gaps, in jurisdiction and enforcement. It is “a broken-down car that somehow keeps moving”, says Harold Koh of Yale University. The ICJ, akin to a civil court, mostly weighs disputes between states, but has jurisdiction over the Genocide Convention. In 2019 it agreed that any party to the convention could bring a genocide case, though it must prove intent to “destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group”.

ICC chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, is reportedly about to issue warrants for the arrest of Israeli political and military leaders (and possibly Hamas figures, too

The ICC more like a criminal court, investigates people rather than states. But it can prosecute a broader range of offenses—not only genocide but also crimes against humanity and war crimes. Independent prosecutors decide whether to issue arrest warrants, but rely on states to enact them. They can charge anyone involved in crimes committed on the territory of countries that have ratified the ICC’s statute, or by their citizens. The ICC can investigate a fourth crime, of “aggression”—regarded as the “supreme international crime” that leads to other atrocities—but only if suspects are citizens of state parties. The ICC’s work is thus limited because dozens of countries have declined to join the court—among them America, Russia, China, India and Israel.

Throw the book at them

The law is moving nevertheless. Start with responses to the war in Ukraine. The ICC has issued arrest warrants for four Russians, among them Mr Putin, who is wanted on charges related to the deportation of Ukrainian children. In the ICJ, meanwhile, Ukraine has accused Russia of abusing the Genocide Convention by justifying its invasion with the claim that it was acting to halt a Ukrainian “genocide” of Russian-speakers. The ICJ vainly ordered Russia to halt its invasion but ultimately ruled Ukraine’s claim inadmissible. Instead the court will hold hearings on whether Ukraine, rather than Russia, committed genocide. That may seem perverse, but could help debunk Russian propaganda.

Four Ukraine-related cases against Russia are pending at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), an organ of the Council of Europe (distinct from the European Union). They include a claim for compensation that may run to tens if not hundreds of billions of euros. The council has set up a register to which Ukrainians can submit claims.

Russia was expelled from the council in March 2022, but the ECHR retained jurisdiction for events that took place in Russian-controlled occupied lands until the end of the notice period in September 2022. Ukraine will urge the court to consider subsequent events. But its expected push to include damage caused by Russia in the rest of Ukraine may discomfit some European allies that also fight abroad. A favorable decision on damages could further spur moves in Western countries to seize some of almost $300 billion of frozen Russia assets. Enforcing the finding of an international tribunal constitutes solid grounds for confiscating sovereign assets, argues Oona Hathaway, also at Yale.

In the case of Gaza the ICJ admitted South Africa’s genocide case against Israel as “plausible” in January. Pending full hearings, it told Israel to ensure its soldiers do not commit acts of genocide and to allow more humanitarian aid to Gaza, but did not order an immediate ceasefire. As for the ICC, its chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, is reportedly about to issue warrants for the arrest of Israeli political and military leaders (and possibly Hamas figures, too) on charges still undisclosed. Netanyahu denounced the prospect as an “outrage of historic proportions”.

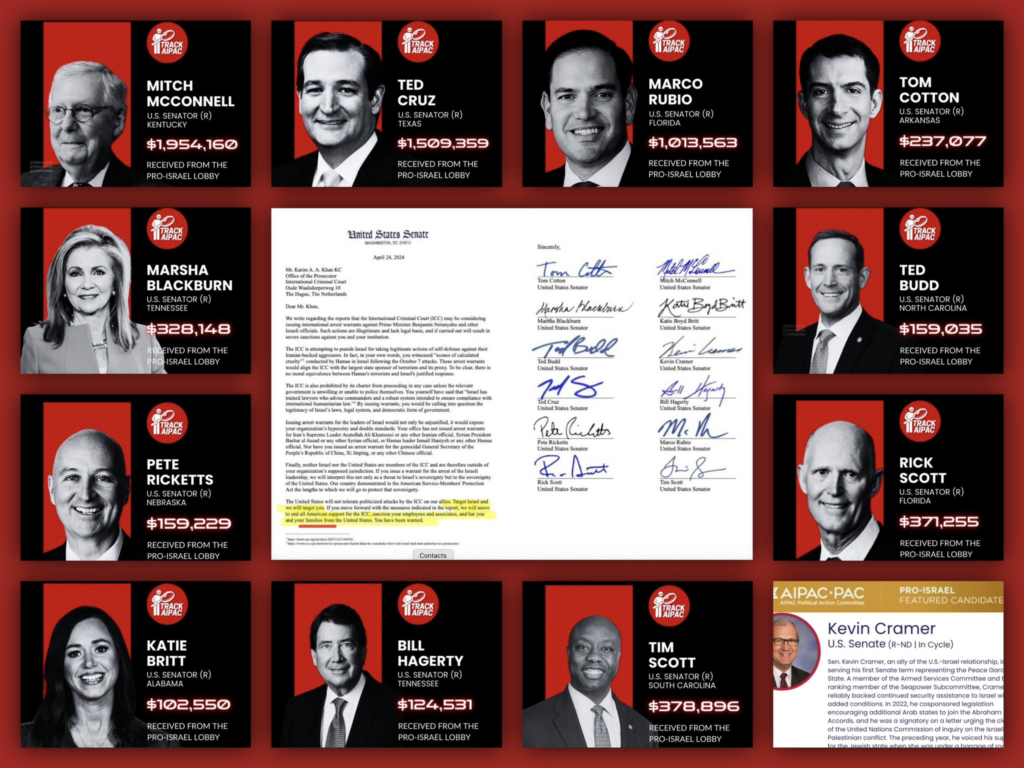

A finding of genocide would be grievous to Israel, a country born from the ashes of the Holocaust. Israel is said to be threatening retaliation against the Palestinian Authority (which, in effect, granted the court jurisdiction in Gaza). Israel’s supporters in Congress call for sanctions against the ICC. Mr Khan, in turn, has demanded an end to “all attempts to impede, intimidate or improperly influence officials”.

All of which is a quandary for the Biden administration. America is not a signatory but has supported the ICC in Ukraine. Yet it says the court lacks jurisdiction in Gaza. America urges Israel to do more to protect Palestinian civilians, but has for months supplied it with weapons. On May 8th America confirmed it had suspended a shipment of heavy munitions out of concern that they might be used in Rafah, where more than 1m Palestinians are sheltering. Despite an international outcry, Israel is starting to push into that city. Talks about a ceasefire ended today in Cairo without any deal.

Human-rights lawyers hope to close some gaps in international law, whether by new agreements (some call for a special tribunal to prosecute Russia for aggression) or by existing courts extending their remit. They also want new curbs on AI and autonomous weapons. But they cannot hold back states bent on violence. Arrest warrants limit leaders’ international travel. But don’t expect to see Mr Putin in the dock.

The US senators that threatened ICC over arrest warrants for Israeli officials

So what is the point of the court battles? Lawyers offer three answers: to impose a reputational and perhaps economic cost on those who spill blood wantonly; to strengthen the negotiating hand of their victims in future diplomatic talks; and, at a minimum, to establish a credible historical record of atrocities. Confronted with an “epidemic of inhumanity”, Mr Khan has argued, the world must “cling to the law” more tightly. The unspoken danger is that, should he and others fail to curb the horrors, the law will collapse and there will be little left to hold onto.

THE ECONOMIST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.