By Steve Coll

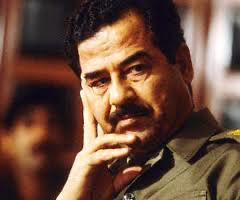

America committed its worst foreign policy mistake of the post-Cold War era when it invaded Iraq in 2003 to disarm Saddam Hussein of his supposed weapons of mass destruction. The war that followed exacted an appalling price in Iraqi and American lives and resources, and it also empowered Iran, energizing regional proxy conflicts that have entrapped Washington in the Middle East, as the Biden administration has rediscovered painfully.

At a time when the United States has identified managing dictatorships in China and Russia as the country’s most important national security challenge and when North Korea’s isolated and idiosyncratic leader holds nuclear weapons and intercontinental missiles, Mr. Hussein’s case offers a rare, well-documented study of why authoritarians often confound American analysts and presidents.

How might the U.S. invasion of Iraq have been avoided? Much of our post hoc investigation has focused on the false and manipulated intelligence about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, President George W. Bush’s choices, the selling of the war, and the media’s complicity. Another central question has rarely been examined: Why did Mr. Hussein sacrifice his long reign in power — and ultimately his life — by creating an impression that he held dangerous weapons when he did not?

The question is answerable. Mr. Hussein recorded his private leadership conversations as assiduously as Richard Nixon. He left behind about 2,000 hours of tape recordings as well as a vast archive of meeting minutes and presidential records. The materials document the Iraqi leader’s thinking at critical junctures of his long conflict with Washington, including his private reactions to Sept. 11 and to the Bush administration’s plans to oust him. And they clarify the complicated matter of why he could not persuade U.N. inspectors, multiple spy agencies, and many world leaders that he did not possess weapons of mass destruction

On the tapes, as he rambles on about world affairs — his colleagues rarely dare to interrupt him — Mr. Hussein can be impressively shrewd and prescient. In October 2001, days after Mr. Bush announced the American-led war on Al Qaeda and the Taliban, Mr. Hussein asked his cabinet: “If America established a new government in Kabul according to its desires, do you think this will end the Afghan people’s problems? No. This will add more causes for so-called terrorism instead of eliminating it.” In the face of American hostility, he dodged and feinted, motivated by two goals above all: to remain in power and to achieve glory in the Arab world, preferably by striking Israel.

Mr. Hussein held profoundly special beliefs about Jews and confused himself with elaborate conspiracy theories about American and Israeli power in the Middle East. He believed that successive U.S. presidents, under the influence of Zionism, conspired secretly and continually with Iran’s radical ayatollahs to weaken Iraq. The Iran-contra conspiracy of the 1980s, when America joined briefly with Israel to sell arms to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s regime, cemented the Iraqi leader’s convictions for years to come. That Iran-contra represented a strain of harebrained incompetence in American foreign policy did not occur to him.

The reasons Mr. Hussein failed to clarify that he had no weapons of mass destruction in the run-up to 2003 are embedded in his tragic, decades-long conflict with Washington: his furtive, mistrustful collaboration with the C.I.A. during the 1980s; the Gulf War of 1990 and 1991; the U.N.-backed struggle over Iraqi disarmament that followed; and the climactic confrontation after Sept. 11.

Shortly after the Gulf War, he secretly ordered the destruction of his chemical and biological arms, as Washington and the United Nations had demanded. He hoped this action would allow Iraq to pass disarmament inspections, but he covered up what he had done and lied repeatedly to inspectors. He did not tell the truth to his own generals, fearing that he might invite internal or external attacks. His decision to comply with international demands but to lie about it to U.N. inspectors defied Western logic. But Mr. Hussein would not submit to public humiliation, not least because he thought it wouldn’t work. “One of the mistakes some people make is that when the enemy has decided to hurt you, you believe there is a chance to decrease the harm by acting in a certain way,” he told a colleague. In fact, he said, “The harm won’t be less.

MR. HUSSEIN BELIEVED THE C.I.A. WAS ALL BUT OMNISCIENT, AND SO, PARTICULARLY AFTER SEPT. 11, WHEN MR. BUSH ACCUSED HIM OF HIDING WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION, HE ASSUMED THAT THE AGENCY ALREADY KNEW THAT HE HAD NO DANGEROUS WEAPONS AND THAT THE ACCUSATIONS WERE JUST A PRETENSE TO INVADE.

A C.I.A. capable of making an analytical mistake on the scale of its miss about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction was not part of his worldview.

While researching Mr. Hussein’s conflict with America, I sued the Pentagon, and with help from the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, I obtained a batch of his tapes and files, including some never released. They proved invaluable for my book project, but it is unfortunate that I had to go to such trouble. It is plainly in the interests of the United States that the full archive be made available to researchers so that insights about Mr. Hussein’s dictatorship can inform the American public and their government.

My work concerned the back story of the 2003 invasion, largely from the Iraqi leader’s perspective. Yet I could not help reflecting on how U.S. decision-makers might have done better and what lessons their failures might hold today. Mr. Hussein was not the first mass killer I had written about in-depth, but I was reminded about how difficult and uncomfortable it can be to fully empathize with someone who acts and thinks in ways you find appalling. Yet it is all but impossible to understand or influence other people without suspending judgment and seeking to see the world from behind their eyes. As a writer, I had the means to humanize Mr. Hussein without sanitizing him. I could also discern how hard it would be for an elected American president to attempt this.

The incentives of competitive democratic politics reward the demonization of enemies and offer little credit for reflecting thoughtfully about a tyrant or for bucking conventional wisdom about his motives. In theory, nonpartisan intelligence analysts at the C.I.A. and other agencies should be able to think and advise freely about the character and motives of America’s most dangerous adversaries. In reality, career analysts too often fall into groupthink that recycles prevailing political or public opinion. That certainly helps to explain the intelligence community’s misjudgments about Mr. Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction.

Domestic political incentives also discourage presidents from talking to enemy autocrats, not least because doing so might undermine economic sanctions the United States is trying to enforce. “If I weren’t constrained by the press, I would pick up the phone and call the son of a bitch,” President Bill Clinton told Prime Minister Tony Blair of Britain privately in 1998, discussing Mr. Hussein. “But that is such a heavy-laden decision in America. I can’t do that.” Indeed, after early 1991, so far as is known, no significant American official ever talked directly with Mr. Hussein or his top envoys. Only after his capture in December 2003, when he shared cigars with various C.I.A. and F.B.I. interrogators at a prison outside Baghdad, did he begin to offer insights that helped to explain America’s misjudgments about him.

As one of Mr. Hussein’s aides once put it, citing an Arab proverb, “You overlook many truths from a liar.” The best way to avoid that is through periodic private conversation. Such contact with Mr. Hussein before 2003 might have revealed that as he reached his 60s, he had lost much of his prior interest in military affairs and had become obsessed with writing novels.

In his many contradictions and inconsistencies, Mr. Hussein was not an unusual dictator. Important features of his reign are often found in autocracies — paranoia about threats to the leader’s power, unreliable information provided by unctuous and terrified aides and an inability to fully grasp adversaries’ intentions.

Like Vladimir Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un today, Mr. Hussein unnerved the world by talking loosely about nuclear war. During the conflict over Kuwait, he was so convinced that an atomic strike by Israel or America was coming that he commissioned plans to evacuate Baghdad’s population to the countryside. His thinking rattled even his ruthless cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid, known as “Chemical Ali,” who was later hanged for his role in the gassing of Kurdish civilians during the 1980s. “All this hoopla about the effects of nuclear and atomic attack … frightens children,” he complained during one recorded meeting.

To which Mr. Hussein exclaimed: “What are we, a bunch of kids? I swear on your mustache … pay attention to civil defense!”

Yet the Iraqi leader wanted to avoid a nuclear conflict. The most important lesson from his example may be that even a reckless dictator can be deterred from aggression if he understands clearly that his life, legacy or hold on power may be lost.

Deceived by Mr. Hussein and misled by bad advice from Arab allies, President George H.W. Bush failed to deliver a clear deterrence message to the Iraqi leader before Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990. The president corrected that error early in 1991, as he prepared to order a U.S.-led force to oust Iraqi troops from the emirate. He dispatched Secretary of State James Baker to convey to Mr. Hussein’s chief envoy that if Iraq gassed American troops, the United States would take down his government. Mr. Baker did not mention nuclear weapons, but the Iraqi leader already believed that America would not hesitate to drop atomic bombs. As war neared, he deployed chemical weapons to strike U.S. and allied soldiers, but he hesitated at the moment of decision and did not use gas. Months later, he destroyed the weapons. Deterrence worked.

It may not always work. Mr. Hussein’s case is a paradox. He was erratic enough that it would have been unwise to gamble with America’s security by guessing at his intentions. The better policy was to act on the basis of Iraq’s capabilities and to issue clear and convincing deterrence messages. Yet in the end, America made a profound misjudgment about his weapons of mass destruction capabilities because it failed to understand who he really was.

Mr. Coll is an editor at The Economist and the author of “The Achilles Trap: Saddam Hussein, the C.I.A., and the Origins of America’s Invasion of Iraq.”

The New York Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.