Beirut,

Evidence implicates senior Lebanese officials in the August 4, 2020, explosion in Beirut that killed 218 people, but systemic problems in Lebanon’s legal and political system are allowing them to avoid accountability, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The UN Human Rights Council should mandate an investigation, and countries with Global Magnitsky and similar human rights and corruption sanctions regimes should sanction officials implicated in ongoing violations of human rights resulting from the August 4 explosion and efforts to undermine accountability.

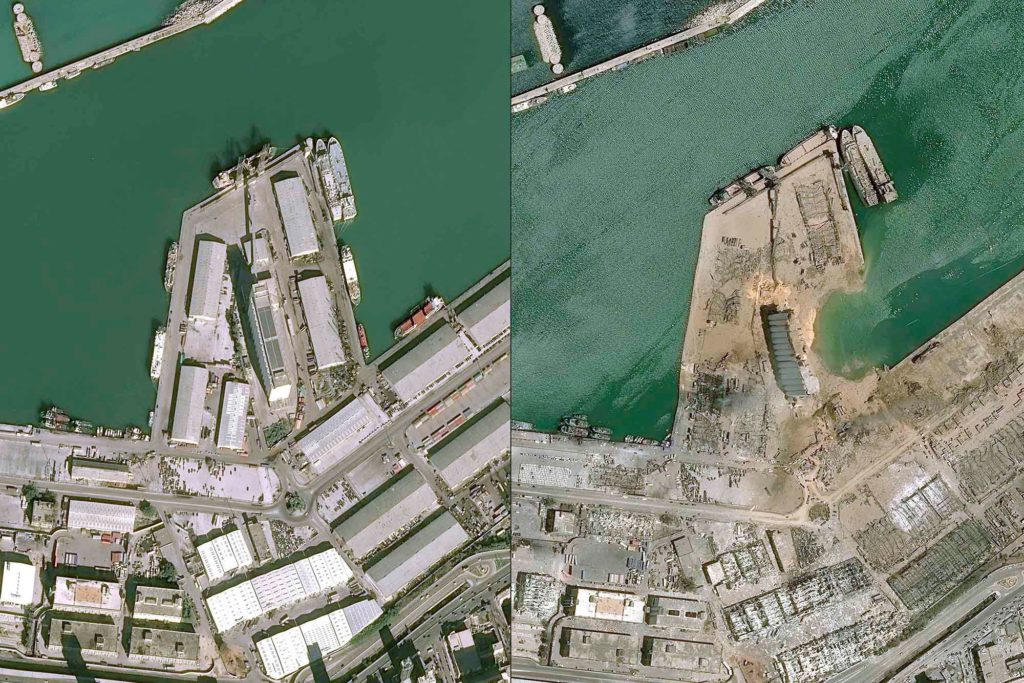

The 127 page report, “‘They Killed Us from the Inside’: An Investigation into the August 4 Beirut Blast,” sets out the evidence of official conduct, in a context of longstanding corruption and mismanagement at the port, that allowed for tonnes of ammonium nitrate, a potentially explosive chemical compound, to be haphazardly and unsafely stored there for nearly six years. The detonation of the chemical caused one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history, pulverizing the port and damaging over half the city.

“The evidence overwhelmingly shows that the August 2020 explosion in Beirut’s port was caused by the actions and omissions of senior Lebanese officials who failed to accurately communicate the dangers posed by the ammonium nitrate, knowingly stored the material in unsafe conditions, and failed to protect the public,” said Lama Fakih, crisis and conflict director at Human Rights Watch. “A year later, the scars of that devastating day remain etched in the city while survivors and families of the victims await answers.”

Human Rights Watch drew on official correspondence regarding the Rhosus, the ship that brought the ammonium nitrate to the port, and its cargo, some of which has not been published before, and interviews with government, security, and judicial officials, to outline how the dangerous material arrived and was stored at the port. Human Rights Watch also detailed what government officials knew about the ammonium nitrate and what actions they took or failed to take to safeguard the population.

The evidence to date raises questions regarding whether the ammonium nitrate was intended for Mozambique, as the Rhosus‘s shipping documents stated, or whether Beirut was the intended destination. The evidence currently available also indicates that multiple Lebanese authorities were, at a minimum, criminally negligent under Lebanese law in their handling of the cargo, creating an unreasonable risk to life, Human Rights Watch said.

Further, official documentation strongly suggests that some government officials foresaw and tacitly accepted the risks of death posed by the ammonium nitrate’s presence in the port. Under domestic law, this could amount to the crime of homicide with probable intent, and/or unintentional homicide. Under international human rights law, a state’s failure to act to prevent foreseeable risks to life violates the right to life.

Ministry of Public Works and Transport

Officials within the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, which oversees the port, were warned about the danger, yet failed to correctly communicate it to the judiciary or to adequately investigate the potentially explosive and combustible nature of the ship’s cargo, and the danger it posed. They then knowingly stored the ammonium nitrate alongside other flammable or explosive materials for nearly six years in a poorly secured and poorly ventilated hangar in the middle of a densely populated commercial and residential area, contravening international ammonium nitrate safe storage and handling guidance. They also reportedly failed to adequately supervise the repair work undertaken on hangar 12 that may have triggered the explosion on August 4, 2020.

April 2, 2014 Ship Inspection Service staff inspect the Rhosus and find that the conditions of the ship have deteriorated and note that there is hazardous cargo on board. The Rhosus, 2014. Photo: Anthony Vrailas

The Rhosus, 2014. Photo: Anthony Vrailas

April 2, 2014

The Beirut harbor master sends a letter to the director of the Directorate General of Land and Maritime Transport telling him water is leaking into the Rhosus and that there is ammonium nitrate, a hazardous substance, on board.

April 7, 2014

The law firm representing the Rhosus‘s captain sends a letter to the Directorate General of Land and Maritime Transport, stating that ammonium nitrate is highly flammable and is used to manufacture explosives, and that care needs to be taken in transporting and storing it. The lawyers attach a 16-page “Timeline of major disasters” caused by ammonium nitrate explosions.

April 8 – June 2, 2014

The director of the Directorate General of Land and Maritime Transport sends three letters to the Case Authority, which is the Lebanese state’s lawyer, requesting that they take measures to sell the ship and its cargo. The letters focus only on the risk posed by the cargo due to its presence on a ship that is at risk of sinking, failing to mention that even on land it is potentially explosive and needs to be secured.

June 27, 2014

On the basis of the inaccurate and incomplete information provided to him, the judge of urgent matters orders the ministry refloat the ship after moving and storing the ammonium nitrate in a “suitable place that it chooses,” and for it to be “under [the ministry’s] protection after taking the necessary precautions given the dangers posed by the material on board.“

October 23 – 24, 2014

Port authorities transfer the ammonium nitrate from the Rhosus to hangar 12, which was not an appropriate storage site. They store the ammonium nitrate alongside flammable and hazardous material in a congested and haphazard way, only hundreds of meters from a residential area, contrary to international guidelines.

December 18, 2017 – September 12, 2018

After cargo is offloaded, correspondence between the Ministry, signed by then Public Works Minister Fenianos, and the Case Authority continues to mischaracterize the threat posed by the ammonium nitrate.

June 1, 2020

The Cassation Public Prosecutor instructs the Port Authority via State Security to provide security for hangar 12, appoint a warehouse keeper, and fix the doors and walls.

August 1 – 4, 2020

Workers conduct maintenance work on hangar 12 based on the Cassation public prosecutor’s instructions, reportedly without Port Authority supervision and without knowledge of the material inside the hangar.

Pictures from inside Hangar 12

Pictures from inside Hangar 12

Ministry of Finance

Official correspondence with customs officials, under the Finance Ministry, reflects that a range of ministry officials were aware of the dangers. Customs officials stated that they sent at least six letters to the judiciary requesting the sale or export of the material. But court records show that the customs officials were repeatedly told that their requests were procedurally incorrect. Judicial officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that customs did not need judicial authorization to sell, re-export, or destroy the material.

February 21, 2014

Customs official Colonel Joseph Skaf warns other customs officials that the Rhosus is “carrying highly dangerous and explosive Ammonium Nitrates that threaten public safety.”

Skaf died in March 2017 in suspicious circumstances, leading some to believe he was assassinated. At least three other murders of people thought to have information about the ammonium nitrate or the August 4 explosion have also been reported.

Colonel Joseph Skaf

October 24, 2014

As the ammonium nitrate is being unloaded into hangar 12, customs official Nehme Brax warns that the material is dangerous and could ignite, and that Beirut’s port does not have the facilities necessary to safely store the cargo.

Brax warns of the dangers of the ammonium nitrate catching fire or exploding on at least three other occasions, on May 9, 2015; February 1, 2016; and March 14, 2018.

December 5, 2014 – December 28, 2017

Customs directors send at least six letters to urgent matters judges requesting they re-export or sell the ammonium nitrate.

Each time, the urgent matters judge responds in the same way, returning the letters on procedural grounds and noting that they do not have jurisdiction to authorize these measures. But five judicial sources told Human Rights Watch that the Customs Administration did not need judicial authorization to remove the cargo, either by selling it, destroying it, or re-exporting it.

Lebanese Armed Forces

The Lebanese Army Command brushed off knowledge of the ammonium nitrate, saying they had no need for it, even after learning that its nitrogen grade classified it under local law as material used to manufacture explosives and required army approval to be imported and inspection. Military Intelligence, responsible for all security issues related to munitions, drugs, and violence at the port, took no apparent steps to secure the material or establish an emergency response plan or precautionary measures.

November 19, 2015

The army commander’s chief of staff requests laboratory testing to confirm the nitrogen grade of the ammonium nitrate. This is the first record available indicating the army’s knowledge of the ammonium nitrate.

February 27, 2016

Customs informs the Army Command that based on tests conducted by an expert, the nitrogen grade of the ammonium nitrate at the port is 34.7 percent.

Under the Weapons and Ammunition Law, the Lebanese army is responsible for giving prior approval for importing military equipment and ammunition, including ammonium nitrate with a nitrogen grade above 33.5 percent, and must inspect explosive substances that arrive to the country through its ports.

April 7, 2016

Despite this, the army commander’s chief of staff responds to customs stating that the army has no need for the ammonium nitrate and suggesting it be sold to a private company or that it be re-exported.

After the August 4, 2020 explosion

The Army Command releases several statements announcing it has removed and safely destroyed dangerous and hazardous material at Beirut’s port, including 4,350 kilograms of ammonium nitrate. This indicates that commanders could have acted similarly to secure and remove the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12.

Interior Ministry

Both the then-Minister of Interior and the Director General of General Security have acknowledged that they knew about the ammonium nitrate aboard the Rhosus, but have said that they did not take action after learning about it because it was not within their jurisdiction to do so.

State Security

Sources indicated that State Security, an arm of the Higher Defense Council, which implements the country’s defense policy, was aware of the existence of the ammonium nitrate and its dangers since at least September 2019. But there was an unconscionable delay in reporting the threat to senior officials, and the information provided was incomplete. The first correspondence State Security sent to the president and the prime minister was on July 20, 2020, two weeks before the explosion.

September 2019

According to confidential sources, Nehme Brax, a customs official, informs Major Joseph Naddaf about the ammonium nitrate in hangar 12. Naddaf headed the State Security office at the port, tasked with investigating corruption.

January 27, 2020

Major General Tony Saliba, the State Security director, orders Naddaf to investigate the ammonium nitrate issue and present his findings to the competent judicial authority.

Major General Tony Saliba

May 28, 2020

Naddaf concludes his initial investigation and presents his findings via telephone to Cassation Public Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat, who orders Naddaf to summon two port officials for interrogation . Naddaf writes that he was informed by a chemistry expert that if the ammonium nitrate were to ignite, it would lead to “a huge explosion with catastrophic consequences on the port of Beirut.”

June 1 – June 4, 2020

Naddaf concludes his investigation on June 1, 2020 and refers one copy of his report to Judge Oueidat and another to the Directorate General of State Security. The report was sent to the Directorate General of State Security on June 3, 2020. Judge Oueidat received the report on June 4, 2020.

Oueidat orders State Security to instruct the port authorities to secure the hangar.

June 3, 2020

While disputing the circumstances under which it happened, both Saliba and Prime Minister Hassan Diab have confirmed that the prime minister learned about the ammonium nitrate on June 3 via phone. Caretaker Prime Minister Diab has said that on the same evening he requested State Security finalize their report within days, but Saliba said Diab did not ask for such a report.

It is not clear why Saliba did not send Diab Naddaf’s finalized report and claimed that the investigation was incomplete.

Prime Minister Hassan Diab

July 20, 2020

State Security sends a report about the ammonium nitrate to the president and the prime minister, which reiterated the findings of Naddaf’s investigation and warned that the ammonium nitrate “could be used to make explosives as it is highly explosive and very flammable.” It excluded the warning in Naddaf’s report that if the ammonium nitrate were to ignite, it would lead to “a huge explosion with catastrophic consequences on the port of Beirut.”

It is unclear why it took almost six weeks between Naddaf’s investigation being finalized and a report being sent to the president and prime minister.

President Michel Aoun

Higher Defense Council

President Michel Aoun, the chair of the Higher Defense Council, admitted that he had been aware of the ammonium nitrate’s presence since at least July 21, 2020, and had asked an advisor to follow up, but claimed that he was not responsible. Prime Minister Hassan Diab, the council’s vice-chair, had been aware of the ammonium nitrate’s presence since June 3, 2020, but took no apparent action beyond referring State Security’s July 20, 2020 report to the Justice and Public Works ministries.

June 3, 2020

Prime Minister Hassan Diab is first made aware of the ammonium nitrate in the port.

Based on this information, Diab said he decided to go to the port the next day and sent his security detail to the port that evening to obtain more information. His security detail gave him information that conflicted with what he was initially told, so Diab said he decided to cancel his visit and instructed his security detail to ask State Security for a report within days.

Diab told Human Rights Watch that: “I then forgot about it, and nobody followed up. There are disasters every day.”

Prime Minister Hassan Diab

July 20, 2020

State Security sends a report to the president and the prime minister, summarizing the findings of State Security’s investigation and warning that the 2700 tons ammonium nitrate in hangar 12 “are used to make explosives, as they are very explosive and highly flammable.”

President Michel Aoun confirms receiving this report on July 21, 2020, but claims he instructed his security advisor to follow up and that he was not responsible. He later said that when he found out about the ammonium nitrate at the port, it was “too late.” President Aoun has the power to unilaterally convene a meeting of the Higher Defense Council.

Prime Minister Hassan Diab confirms receiving this report on July 22, 2020, but states that he was not aware of how explosive ammonium nitrate was until after the blast. Asked why he did not know this given that the State Security report explicitly mentioned the dangers posed by ammonium nitrate, he said he did not go through the 30 pages of the report and that he gave it to his security advisor. In response to a letter from Human Rights Watch asking for clarification as to why he did not read the report, Diab wrote that he did read it. The State Security report, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, is three pages long with six pages of annexes.

The Beirut port explosion killed 218 people, and wounded 7,000, leaving at least 150 with a physical disability. It caused untold psychological harm, and damaged 77,000 apartments, displacing over 300,000 people. According to the World Bank, the explosion caused an estimated US$3.8-4.6 billion in material damage.

Lebanese officials vowed to investigate vigorously and expeditiously. But in the year since the explosion, procedural and systemic flaws in the domestic investigation have rendered it incapable of credibly delivering justice. These flaws include a lack of judicial independence, immunity for high-level political officials, lack of respect for fair trial standards, and due process violations.

Survivors of the explosion and the families of the victims have been vocal in calling for an international investigation, expressing their lack of faith in domestic mechanisms.

The case for an international investigation has strengthened. The UN Human Rights Council should mandate an investigation to identify the causes of and responsibility for the August 4 explosion, and the steps needed to ensure an effective remedy for victims and to prevent further rights violations, Human Rights Watch said.

Countries with Global Magnitsky and other human rights and corruption sanctions regimes should sanction Lebanese officials implicated in ongoing violations of human rights related to the explosion and efforts to undermine accountability, Human Rights Watch said. Such sanctions would reaffirm those countries’ commitments to promoting accountability for serious human rights abuse and provide additional leverage to those pressing for accountability through domestic judicial proceedings.

“Despite the devastation wrought by the blast, Lebanese officials continue to choose the path of evasion and impunity over truth and justice,” Fakih said. “The UN Human Rights Council should immediately authorize an investigation, and other countries should impose targeted sanctions on those implicated in ongoing abuses and efforts to impede justice.”

Read the full report “They Killed Us from the Inside”: An Investigation into the August 4 Beirut Blast »

More on Human Rights Watch’s work on Lebanon »

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.