Successive governments have hyped hydrocarbons as as potential game-changer for an economy that is now in a deep crisis.

Beirut, Lebanon – Lebanon is learning a hard lesson in the perils of over-hyping a potential solution to the country’s economic ills – and at the worst of times, no less.

For years, government officials have touted offshore natural gas reserves as a would-be saviour of Lebanon’s fragile finances and the bedrock of a long-overdue energy revolution.

On Monday, the country’s Energy Minister, Raymond Ghajar, delivered a sobering reality check on those grandiose plans, announcing that the country’s first foray into hydrocarbon exploration had found no commercially-viable amount of gas to develop.

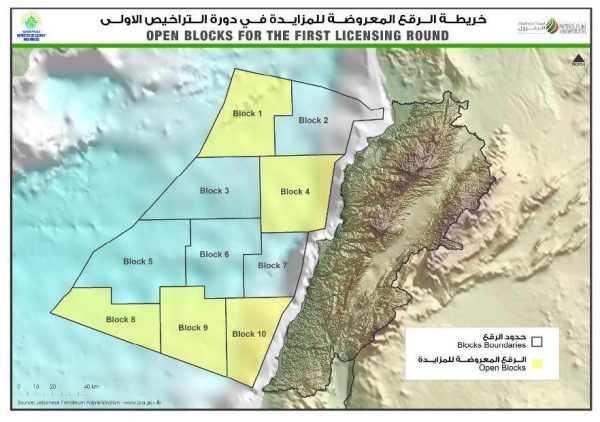

Though the exploration of “block 4”- one of 10 blocks claimed by Lebanon in the Levant Basin in the eastern Mediterranean Sea – found no large reservoir, Ghajar said it had uncovered several small pockets of gas and a “petroleum system”, indicating that a larger find may be present elsewhere in Lebanon’s waters.

Though this could yet turn out to be a positive signal for the development of Lebanon’s nascent natural gas sector, analysts say the initial findings are a huge letdown after years of government failure to manage expectations.

“It would have been a long shot to strike a commercial discovery from our first drilling,” Mona Sukkarieh, a political risk consultant focused on oil and gas in Lebanon, told Al Jazeera. “Offshore exploration is a long process, with a lot of challenges and uncertainties.”

In 2017, an international energy consortium including French oil giant Total, Italy’s ENI and Russia’s Novatek was awarded contracts to drill in block 4, as well as southern block 9.

Membership delayed

Successive governments have hyped hydrocarbons as a source of income for the cash-strapped, debt-addled state. Lebanon’s economy is buckling under some $90bn of debt – giving it the infamous distinction of having the third-highest debt burden in the world compared to the size of its economy.

Lebanon defaulted on a $1.2bn Eurobond in March and is now seeking to restructure all of its debt. Its currency has since depreciated by more than 50 percent on parallel markets. Thousands have lost their jobs and Human Rights Watch has warned that millions are at risk of being unable to secure basic needs such as food.

Instead of dealing with the state’s ailing finances through structural reforms or by fighting eye-watering levels of corruption, Lebanon’s ruling establishment has always waited for money to come in from outside – preferably with as few strings attached as possible – via successive international donor conferences or from rich Gulf nations.

Oil and gas revenues fit nicely into that paradigm.

Cabinet policy statements have long referred to oil and gas “wealth” hidden underneath Lebanon’s sea, and the 2019 budget was partially based on the supposed “solid ground” of the so-far non-revenue-generating sector.

On the night before the inaugural drilling process commenced in late February, President Michel Aoun gave a televised speech to the nation to announce that Lebanon had entered “the club of oil nations.”

That membership delayed, Energy Minister Raymond Ghajar was forced to pivot on Monday, couching the findings from block 4 as “a wealth of information” that will be used to better target exploration in block 9.

“This is only the beginning,” Laury Haytayan, MENA director at the National Resource Governance Institute, told Al Jazeera.

“Lebanon has to wait at the doorsteps of the club – we’re not in the club of producers until a discovery is made and production starts.”

A lost decade

Lebanon’s offshore exploration had been delayed by about a decade as the country struggled with political paralysis and low-level conflict, while other nations, notably Israel, Cyprus and Egypt, made major discoveries in the deep waters of the eastern Mediterranean.

Now the crippling of the world economy as a result of the COVID0-19 pandemic and the huge drop in the price of benchmark global Brent crude oil below $20 a barrel throws Lebanon’s hydrocarbon hopes into further uncertainty – at least in the foreseeable future.

“The coronavirus pandemic will reflect on companies’ exploration budget over the coming period, especially offshore exploration in deep and ultra-deep waters,” Sukkarieh said, referring to Lebanon’s case where drilling took place at a depth of around 4,000 metres (13,123 feet).

“But on a longer term, the outlook is more nuanced and interest is likely to pick up again,” Sukkarieh said.

Meanwhile, exploratory drilling was supposed to commence in block 9 before the end of 2020, but Ghajar said that the consortium may choose to push back that timetable.

Lebanon has also delayed the submission of bids for a second offshore licensing round twice, most recently pushing the deadline to June 1.

Even if a large gas reservoir had been found in block 4, the sector’s development takes years, and Lebanon’s economy is in crisis now.

Lebanon’s draft rescue plan says that it needs between $10bn to $15bn in external financing this year.

Meanwhile, it will take between seven and nine years to extract any hydrocarbons found in its waters – if and when a discovery is made.

This means revenues would take about a decade to begin flowing into the coffers of a state that is struggling to chart its way through the next few months.

( AL JAZEERA NEWS)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.