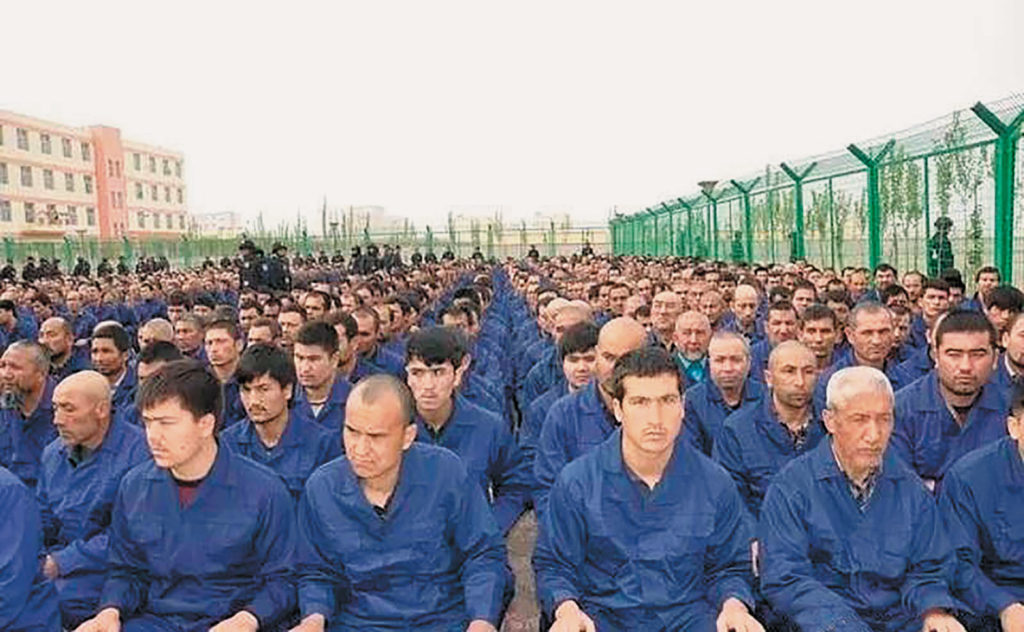

HONG KONG — Internal Chinese government documents obtained by The New York Times have revealed new details on the origins and execution of China’s mass detention of as many as one million Uighurs, Kazakhs and other predominantly Muslim minorities in the Xinjiang region.

The 403 pages reveal how the demands of top officials, including President Xi Jinping, led to the creation of the indoctrination camps, which have long been shrouded in secrecy. The documents also show that the government acknowledged internally that the campaign had torn families apart — even as it explained it as a modest job-training effort — and that the program faced unexpected resistance from officials who feared a backlash and economic damage.

A member of the Chinese political establishment who requested anonymity brought the documents to light in hopes that their disclosure would prevent Communist Party leaders, including Mr. Xi, from escaping responsibility for the program. It is one of the most significant leaks of papers from inside the ruling Communist Party in decades.

Here are five takeaways from the documents.

Privately, officials were blunt about the consequences.

The Chinese government has described its efforts in Xinjiang as a benevolent campaign to curb extremism by training people to find better jobs. But the documents reveal the party’s efforts to organize a ruthless campaign of mass detention in the name of curbing terrorism, a program whose consequences they discussed with cool detachment.

The papers describe how parents were taken away from children, how students wondered who would pay their tuition, and how crops could not be planted or harvested for lack of workers. Yet officials were directed to tell people that they should be grateful for the Communist Party’s help, and that if they complained, they might make things worse for their family

Xi set the course by calling for a war on extremism.

Mr. Xi, the party chief, laid the groundwork for the crackdown in a series of speeches delivered in private to officials during and after a visit to Xinjiang in April 2014, just weeks after Uighur militants stabbed more than 150 people at a train station, killing 31.

He called for an all-out “struggle against terrorism, infiltration and separatism” using the “organs of dictatorship” and to show “absolutely no mercy.”

The documents do not record him directly ordering the creation of the detention facilities, but he ascribed Xinjiang’s instability to the widespread influence of toxic beliefs and demanded they be eradicated.

Attacks overseas spurred worries at home.

Terrorist attacks abroad and the drawdown of American troops in Afghanistan heightened the leadership’s fears and helped shape the crackdown. Officials argued that attacks in Britain resulted from policies that put “human rights above security,” and Mr. Xi urged the party to emulate aspects of America’s “war on terror” after the Sept. 11 attacks.

Mr. Xi signaled a break from the policies of his predecessor, Hu Jintao, who responded to deadly 2009 riots in Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi, with a clampdown but also stressed economic development as a cure for ethnic discontent — longstanding party policy.

“In recent years, Xinjiang has grown very quickly and the standard of living has consistently risen, but even so ethnic separatism and terrorist violence have still been on the rise,” Mr. Xi said in a speech to party officials. “This goes to show that economic development does not automatically bring lasting order and security.”

A new boss in the region ordered mass roundups.

The internment camps in Xinjiang expanded rapidly after the appointment in August 2016 of a zealous new party boss for the region, Chen Quanguo. He distributed Mr. Xi’s speeches to justify the campaign and exhorted officials to “round up everyone who should be rounded up.”

Mr. Chen led a campaign akin to one of Mao’s turbulent political crusades, in which top-down pressure on local officials encouraged overreach, and any expression of doubt was treated as a crime.

Some officials were purged for resisting the campaign.

The crackdown encountered doubts and resistance from local officials who feared it would exacerbate ethnic tensions and stifle economic growth. Mr. Chen responded by purging officials suspected of standing in his way, including one county leader who was jailed after quietly releasing thousands of inmates from the camps.

That leader, Wang Yongzhi, built sprawling detention facilities and increased security funding in the county he oversaw. But in a 15-page confession, which he most likely signed under duress, he worried that the crackdown would harm ethnic relations and that the mass detentions would make it impossible to achieve the economic progress he needed to earn a promotion.

Quietly, he ordered the release of more than 7,000 internment camp inmates — an act of defiance for which he would be detained, stripped of power and prosecuted.

MSN

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.