By Raf Sanchez

Recep Tayyip Erdogan sat in stony silence as he listened to the complaints of his citizens.

During his final drive for votes ahead of Sunday’s elections, the Turkish president agreed to go on a popular radio call in show, where the host nervously played recordings of people who had phoned in with their gripes.

The callers raised bread-and-butter issues that any democratic politician might expect to face – hospital waiting times, school exams, small business regulations – but Mr Erdogan’s face darkened as he answered.

“The things that they have said are not true,” he told the host. “They haven’t said these things after serious examinations and because of that I deplore them [the claims].”

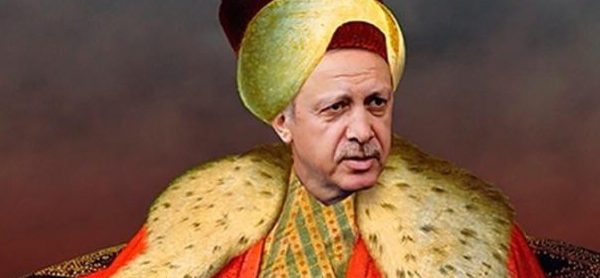

Fifteen years after Mr Erdogan first took over as prime minister of Turkey, he appears on the cusp of an election victory under a new constitutional framework that would make him more powerful than ever.

Thanks to a controversial referendum he pushed through last year, Mr Erdogan would become the country’s first executive president, with sweeping authorities to pass laws by decree and exert control over the judiciary.

To critics at home and abroad, Mr Erdogan’s power is growing at a time when he is angrier and more erratic than ever: refusing to accept even mild criticism of his rule, cut off from Turkey’s economic reality, and blaming unseen enemies for his country’s problems.

“Erodgan lives in an echo chamber that he has created,” said Soner Cagaptay, author of The New Sultan, a biography of Mr Erdogan. “And he’s in there with the 40 million Turks who support him and all of his political advisers.”

The new presidential system will mean Mr Erdogan’s own temperament is more central than ever to Turkey’s governance, as neither ministers nor parliament will have much standing to constrain him.

His unpredictable anger has been most sharply on display in his recent struggle against rising inflation and the falling value of the Turkish lira, which has lost around 20 per cent of its value against the dollar in the last six months.

Mr Erdogan has lashed out against a shadowy international “interest rate lobby”, which he says is determined to strangle Turkey’s economic growth by hiking interest rates. He has hinted he might seize control of the country’s central bank after the election in response.

The comments have alarmed foreign investors, many of whom see Mr Erdogan’s instinct to grab power as a destabilising trend in Turkey.

“Turkey is not like Russia or Iran because we don’t have natural resources,” said Behlul Ozkan, associate professor at Marmara University. “This is Erdgoan’s dilemma: he can’t move to a fully authoritarian system without losing the Western investment that he needs.”

Mr Erdogan has long believed that he is struggling against entrenched foreign and domestic interests trying to undermine his rule. That belief went into hyperdrive after the failed 2016 coup against him, which left 249 people dead.

A paranoid style runs through his inner circle. One of his chief economic advisors suggested that Turkey’s enemies might send “brain waves” to kill Mr Erdogan. Another ally, a former mayor of Ankara, said the 2016 coup plotters used “genies” to recruit fighters to their cause.

Although Mr Erdogan can be a difficult and unpredictable ally, Turkey remains a member of Nato and a key strategic player in the Middle East, meaning Western governments have no choice but to try to work with him.

“Erdogan is not the president he was. He had a very good run for the first five or six years and has got progressively worse,” said one former Western diplomat in Turkey.

“If you talk to Turks they will say that Erdogan is Erdogan and he’s not going to change his spots now. He listens to even fewer people than he used to and he’s convinced that he’s right.”

It is possible that Sunday’s elections will yield a surprise result and that the newly emboldened opposition may be able to force Mr Erdogan into a presidential run-off, where he could be vulnerable in a one-on-one race against his main challenger, Muharrem Ince.

Even if the unified opposition cannot stop Mr Erdogan from winning the presidency, they may be able to stop his Justice and Development Party and their allies from taking a majority in parliament.

But most analysts believe that Mr Erdogan will come out on top, meaning he could potentially be in power until 2028.

For his many supporters in Turkey, the president is still the same political outsider who first came to power in 2003, ushering in an era of rising living standards and strong government. They are untroubled by the idea that one man could rule Turkey for a quarter century.

“Erdogan is the brother of everyone, he is the friend of everyone, he is loved by everyone,” said Mustafa Gerz, a 55-year-old police bus driver. “He should stay president until he dies.”

Yahoo Telegraph

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.