A new global treaty banning cluster munitions has come into force.

The Convention on Cluster Munitions bans the stockpiling, use and transfer of virtually all existing cluster bombs, and also provides for the clearing up of unexploded munitions.

It has been adopted by 108 states, of which 38 have ratified it.

First developed during World War II, cluster bombs contain a number of smaller bomblets designed to cover a large area and deter an advancing army.

Campaigners have hailed the treaty as the most significant disarmament and humanitarian treaty for a decade.

“This is a triumph of humanitarian values over a cruel and unjust weapon,” Thomas Nash, co-ordinator of the Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC), told the BBC.

“At a time when concern over civilian deaths in conflict is in the news, this treaty stands out as a clear example of what governments must do to protect civilians and redress the harm already caused by cluster bombs.”

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said: “This new instrument is a major advance for the global disarmament and humanitarian agendas, and will help us to counter the widespread insecurity and suffering caused by these terrible weapons, particularly among civilians and children.”

The agreement “highlights not only the world’s collective revulsion at these abhorrent weapons, but also the power of collaboration among governments, civil society and the United Nations to change attitudes and policies on a threat faced by all humankind,” Mr Ban said.

Civilian victims

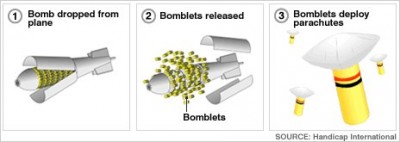

Cluster munitions are weapons dropped by aircraft or fired from the ground, which release submunitions or “bomblets” over a wide area.

If the shrapnel-filled bomblets fail to detonate on impact they can remain active for years. Some are unusually shaped or brightly coloured, making them attractive to children.

The charity Handicap International estimates that 98% of cluster bomb victims are civilians and nearly one-third are children.

“The main problem with cluster bombs is that they kill too many civilians,” says Mr Nash.

“They don’t discriminate between soldiers and civilians in populated areas and so many of them remain unexploded after an attack that they contaminate areas and kill and injure civilians for years.

“They’re one of the worst conventional weapons in the world today.”

The Convention on Cluster Munitions prohibits the production, use, stockpiling and transfer of the weapons.

It sets deadlines for the destruction of stockpiles and the clearance of contaminated land.

Significantly, it also requires countries affected by cluster bombs to help victims of the weapons.

The campaign to ban cluster munitions gained momentum after the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon.

The UN estimates that Israel dropped 4m bomblets onto southern Lebanon during the last three days of the war, when a ceasefire had already been agreed.

Israel insists its use of cluster munitions in Lebanon was in accordance with international humanitarian law and says most were fired at open and uninhabited areas used by Hezbollah fighters.

“Lebanon was the turning point,” says Jeff Abramson from the Arms Control Association, an advocacy group based in Washington.

“It was the international outcry in 2006 that prompted the Norwegian government to start the negotiation process that has led to this new treaty.”

US resistance

But many of the world’s major military powers – including the US, Russia and China – are not signatories to the treaty.

The US administration insists cluster munitions are “legitimate weapons” with “clear military utility in combat”.

It argues that cluster munitions actually cause less harm to civilians than some other weapons.

The US is taking steps to ensure that any cluster munitions used after 2018 have a failure rate of less than 1%.

Despite the absence of important military nations, campaigners believe the Convention on Cluster Munitions will make the use of the weapons unacceptable in future conflicts.

“It’s instructive to look at the 1997 Ottawa Treaty banning anti-personnel landmines,” says the Head of Oxfam’s Control Arms Campaign, Anna MacDonald.

“The United States didn’t sign up to that either but it hasn’t produced or used landmines since the treaty came into force.”

“This treaty will create a new norm – it will stigmatise the weapons,” agrees Mr Nash.

“Twenty-two out of the 28 countries in Nato, including the UK, have joined up to this ban. Practically, morally and in some cases legally it’s going to be extremely difficult for any country to even contemplate using cluster munitions in future.”

1. The cluster bomb, in this case a CBU-87, is dropped from a plane and can fly about nine miles before releasing its load of about 200 bomblets.

2. The canister starts to spin and opens at an altitude between 1,000m and 100m, spraying the bomblets across a wide area.

3. Each bomblet is the size of a drink can and contains hundreds of metal pieces. When it explodes, it can cause deadly injuries up to 25m away.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.