Seven days before Donald Trump’s inauguration as the 45th president, it was as if he was still fighting for election. In a press conference on January 11th, his first for six months, Mr Trump was as thin-skinned, loose-lipped and scrappy as he has ever been. He taunted his rivals and critics, real and suspected; he compared America’s intelligence agencies to Germany’s Nazi regime. He bragged continually (“Nobody has ever had crowds like Trump has had”), scrambling the fact-checkers of media outlets, some of whom he also decried. He called CNN a pedlar of “fake news”. Mr Trump’s fans said they wanted a different kind of leader. America is about to get one.

That Mr Trump seemed exercised was understandable. The previous day CNN reported that the agencies had attached a summary of some unsubstantiated allegations about the president-elect to an intelligence briefing on Russian hacking, which they delivered to Barack Obama and him. Among the allegations, which were reportedly furnished by a British intelligence company working for opponents of Mr Trump, were claims that the Russians held compromising financial and personal information about him, and that members of his campaign team had been in contact with Russian officials.

Mr Trump denounced the claims. Unable to refrain from addressing some of their spicier details, which were published separately online, he claimed that he was too canny to misbehave, as had been luridly alleged, in a foreign hotel room. “In those rooms, you have cameras in the strangest places, cameras that are so small with modern technology.” Anyway, he added, “I’m also very much a germaphobe.” Whether the allegations, which had been circulating among journalists, should have been attached to the intelligence briefing is hard to say. The agencies apparently considered the British source credible; though one or two of its milder claims were swiftly disproved.

Mr Trump’s fulminating against CNN was part of a pattern. Journalists can expect to be lambasted by the next president whenever their reports displease him. In the past few weeks, he has gone after America’s spies, rubbishing the agencies’ conclusion that Russian hackers worked to hurt Hillary Clinton’s chances and boost his, during the election. He also questioned the spooks’ credibility: “These are the same people who said Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction”.

It never looked wise for Mr Trump to lambast proud institutions he will soon preside over. The same could be said of his attacks on judges, generals and environmental regulators. It is tempting to see CNN’s leaked story as an early sign of the backlash such attacks have invited. In his press conference, he was more conciliatory. He said for the first time that he believed Russia was behind the hacking—but, he added, “it could have been others also”.

Mr Trump has made his reputation by stirring conflict. It was his damn-your-eyes style, as much as any policy proposal, that chimed with the anti-establishment sentiment of his keenest supporters. This was not only posturing; he appears to view life, whether in business, politics or trade negotiations, as a series of fights from which only the winner emerges with credit. His victory, naturally, has not changed that. Asked to justify his claim that Americans are not bothered by his, highly irregular, refusal to release his tax returns, despite polling to suggest that they are bothered, Mr Trump replied simply: “I won.” Beneath the bluster, however, he has offered hints of greater pragmatism.

For example, he maintains that he will honour his signature campaign promise, to build a wall along America’s southern border, and make Mexico carry the cost. But he suggests that will not be in terms of “payment”. Perhaps he has in mind the proceeds of another campaign promise, to levy a “major border tax on these companies that are leaving”. In the absence of further details, Republican congressmen will hope this turns out to be less protectionist than it sounds. Some are lobbying Mr Trump’s team to consider a possible alternative arrangement to tariffs, known as border adjustment, designed to incentivise exports. It would involve firms losing the right to deduct the cost of imports from their taxable profits; at the same time, they would no longer be taxed on foreign earnings. It is possible to imagine Mr Trump earmarking Mexico-related revenues from border adjustment to pay for whatever wall, or fence, he ended up building.

To the consternation of some Republican hardliners, he has also weighed in on their efforts to scrap Mr Obama’s health-care reform. As The Economist went to press, Republicans in the Senate were expected to pass a budget plan that would allow them to evade the filibuster and start dismantling Obamacare. Mr Trump says he wants it repealed pronto. But to minimise the disruption this would cause, he also says the reform must be replaced by an alternative arrangement “essentially simultaneously”. That is sensible, even if the time-frame is unrealistic; neither Mr Trump nor his party has settled on an alternative to Obamacare. The issue may prove to be the first test of the accommodation Republican congressmen have made with a leader few supported in the primary.

There was also potential for discord over the Senate confirmation hearings that took place this week for several of Mr Trump’s cabinet picks. One of the most eagerly-awaited, for Senator Jeff Sessions, in fact passed off fairly smoothly. A hardliner on criminal justice and immigration, dogged by historic allegations of racism, Mr Sessions was treated pretty gently by his fellow senators. The putative next secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, former boss of Exxon Mobil, got tougher questions, especially over his former closeness to the Russian government. Mr Tillerson appeared to struggle over Exxon’s past lobbying against possible sanctions on Russia and when asked to condemn President Vladimir Putin as a war criminal.

This was a reminder that concerns about Mr Trump’s strange fondness for Mr Putin go beyond salacious, unverified allegations. It is not clear why the next president seems reluctant to condemn Mr Putin’s excesses or fully accept the conclusion on Russian hacking reached by America’s own spy agencies. That is troubling.

The economist

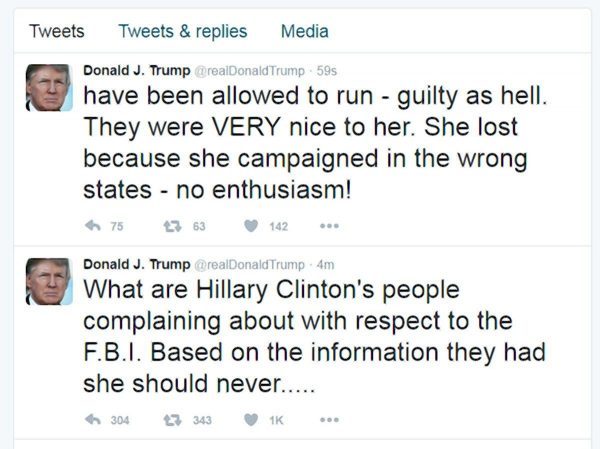

Update : Donald Trump again took to Twitter to berate his former rival Hillary Clinton Friday, calling her “guilty as hell” in a scatterbrained rant that started as an attack on a British spy and an unverified dossier about the President-elect’s ties to Russia.

“What are Hillary Clinton’s people complaining about with respect to the F.B.I. Based on the information they had she should never have been allowed to run – guilty as hell,” he tweeted just after 6 a.m. “They were VERY nice to her. She lost because she campaigned in the wrong states – no enthusiasm!”

The jab — which comes more than two months after Trump won the November election — was apparently aimed at Democrats who have partially blamed their loss on FBI Director James Comey’s decision to reopen the agency’s probe into Clinton’s private email server just days before the 2016 election.

NY DN

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.