Book Review by Deborah Pearlstein

Book Review by Deborah Pearlstein

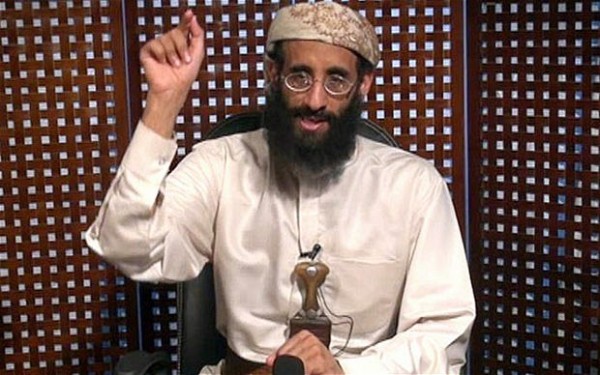

Objective Troy tells the gripping and unsettling story of Anwar al-Awlaki, the once-celebrated American imam who called for moderation after 9/11, a man who ultimately directed his outsized talents to the mass murder of his fellow citizens.

The drive to understand what leads men and women to commit acts of terrorism has animated the work of numerous scholars and inspired much political rhetoric in recent decades. Even as repeated studies refute the notion of a singular correlation between economic privation or government repression and a person’s decision to kill innocent civilians, the hope remains that if we could only identify the social or political pathogen that produces violent extremism, we could develop a cure.

New York Times reporter Scott Shane asks a version of this ambitious question in his new book, “Objective Troy,” the code name given American Anwar al-Awlaki by the U.S. military’s Joint Special Operations Command that killed him. Although Shane’s book, like several others, also details the president’s role in deciding to make Awlaki a target and the circumstances of his killing by remotely piloted drone, its more important contribution is the light it sheds on the larger puzzle of terrorism. As Shane poses the question, “Why did an American who spent many happy years in the United States, launched a strikingly successful career as a preacher, and tried on the role of bridge builder after the 9/11 attacks end up dedicating his final years to plotting the mass murder of his fellow Americans?”

Shane makes no pretense of linking a grand theory of terrorism to the behavior of one man. But as he knows acutely, Awlaki was not just any terrorist. He remains a powerful global influence, credited with plotting multiple terrorist attacks against the United States, including the attempted bombing of a Detroit-bound airliner on Christmas Day 2009. As a study found earlier this year, almost one quarter of terrorism suspects prosecuted by federal authorities in the United States in recent years have been influenced by Awlaki’s message, easily available via the Internet. Understanding the “why” in Awlaki’s case would be no small insight.

Anwar al-Awlaki, the once-celebrated American imam who called for moderation after 9/11, a man who ultimately directed his outsized talents to the mass murder of his fellow citizens. “Objective Troy,” was the code name given al-Awlaki by the U.S. military’s Joint Special Operations Command that killed him

In Shane’s account, two periods emerge as crucial to understanding Awlaki’s transition from freshman-year drinking buddy to international terrorist inspiration. The first came over winter break in 1990, after his first semester of college. Awlaki , in Shane’s words, had “fallen in” with an evangelical group of Islamists, Tablighi Jamaat, or “society for spreading the faith.” He returned to campus as a religious conservative, critical of his roommate’s less fervent commitment to their shared religion. Although the book offers little insight into Awlaki’s understanding of this freshman transformation, it is not hard to imagine his experience as being like that of many undergrads who become seized by a religion or politics or sexuality — and then pursue it with the unique fervor of a young student far from home. One summer during college he traveled to Afghanistan to fight with the mujahideen against the remains of the Russian-backed government.

More important was Awlaki’s second transition, from prominent American Muslim teacher with a successful career and family firmly embedded in the United States to self-imposed exile in Yemen advocating violence against the United States. Awlaki had found success as a preacher soon after college, developing a series of engaging lectures on the lives of the prophets that eventually won him speaking invitations nationwide, and job offers at major mosques in California and, later, Virginia. At the same time, his growing professional prominence, including as an imam at a San Diego mosque that two of the 9/11 hijackers attended, placed him firmly on the FBI’s radar screen after the attacks. While FBI investigators found at best passing connections to radical Islamists, they unearthed Awlaki’s active patronage of a series of prostitutes. The women later provided the FBI with detailed descriptions of multiple sexual encounters with the imam. Shortly after Awlaki learned of the FBI’s discovery, he suddenly left his high-profile job in Virginia and moved away from the United States permanently.

On its face, this story seems to offer a ready answer to the question Shane poses at the outset. Facing personal and professional ruin brought on by his own religiously forbidden sexual behavior, Awlaki turned against his adoptive home and joined the efforts of the already radicalized in attacking it. But Shane sagely insists on exploring another set of explanations, one that should be profoundly more troubling to U.S. counterterrorism policy: that it was the first U.S. invasion of Iraq (over winter break of Awlaki’s freshman year) followed by the U.S. response to the attacks of 9/11, that drove his radicalization. Indeed, as the U.S. government expanded its post-9/11 investigations, rounding up Muslim immigrants, raiding dozens of Islamic institutions and homes, including Awlaki’s, his sermons turned from talk of bridge-building to anger. The 2001 U.S. invasion of Afghanistan perhaps was understandable to him. The 2003 invasion of Iraq was not. Awlaki didn’t hate U.S. freedoms, as President George W. Bush would say of terrorists; he counted on them. What he hated was U.S. policy.

Yet as significant a conclusion as this might be, and consistent with the warnings of dozens of counterterrorism experts who regularly point out the strategic downside of excessive detention and targeting, Shane also determinedly avoids the pat answer that Awlaki was driven to violence by the United States’ actions. Rather, the why in Awlaki’s case is an unavoidable mix of motives, political, yes, but also religious, sexual and ultimately personal. The book is in this respect an admirable embrace of human complexity and an acknowledgment that there are aspects of Awlaki’s thinking we may never fully know. The book delves deeply into a single life and still comes up with questions. This is perhaps its greatest service. It is an object lesson in the limits of the search for a root cause.

THE WASHINGTON POST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.