By JACOB RUSSELL and ADAM HASAN

Amid Lebanon’s crumbling infrastructure and socio-economic decay a cottage industry of crypto miners has found razor-thin profits using hydroelectric power in the mountains.

That puts them into direct competition with local residents over one of country’s most prized resources: electricityBy JACOB RUSSELL and ADAM HASAN

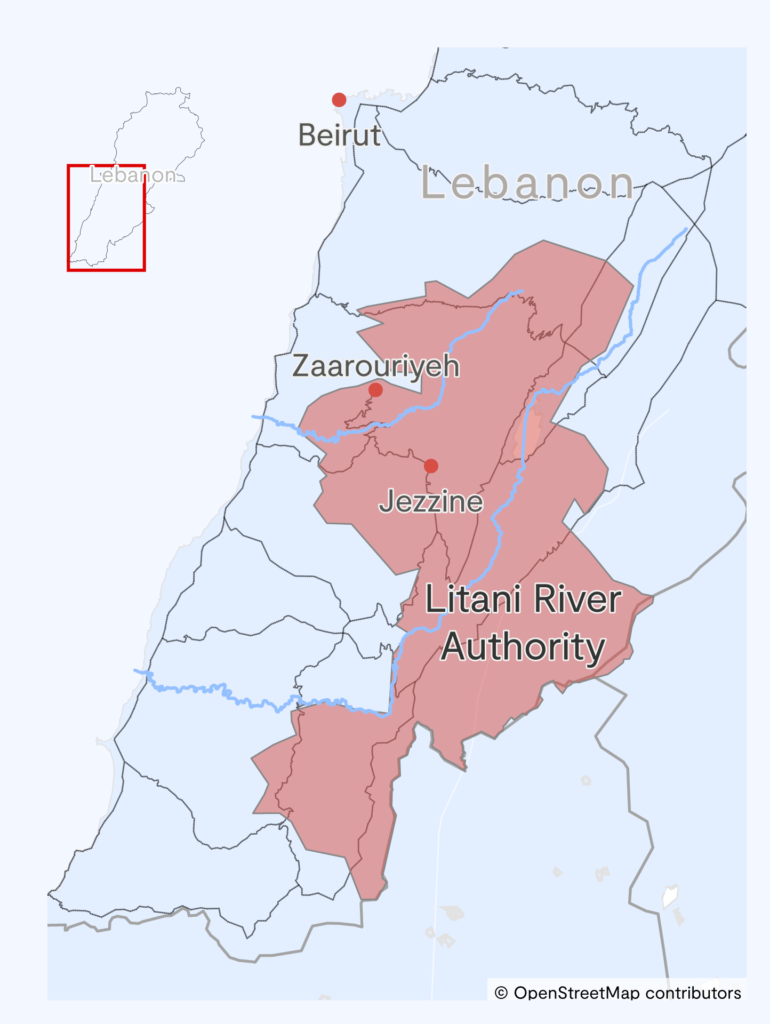

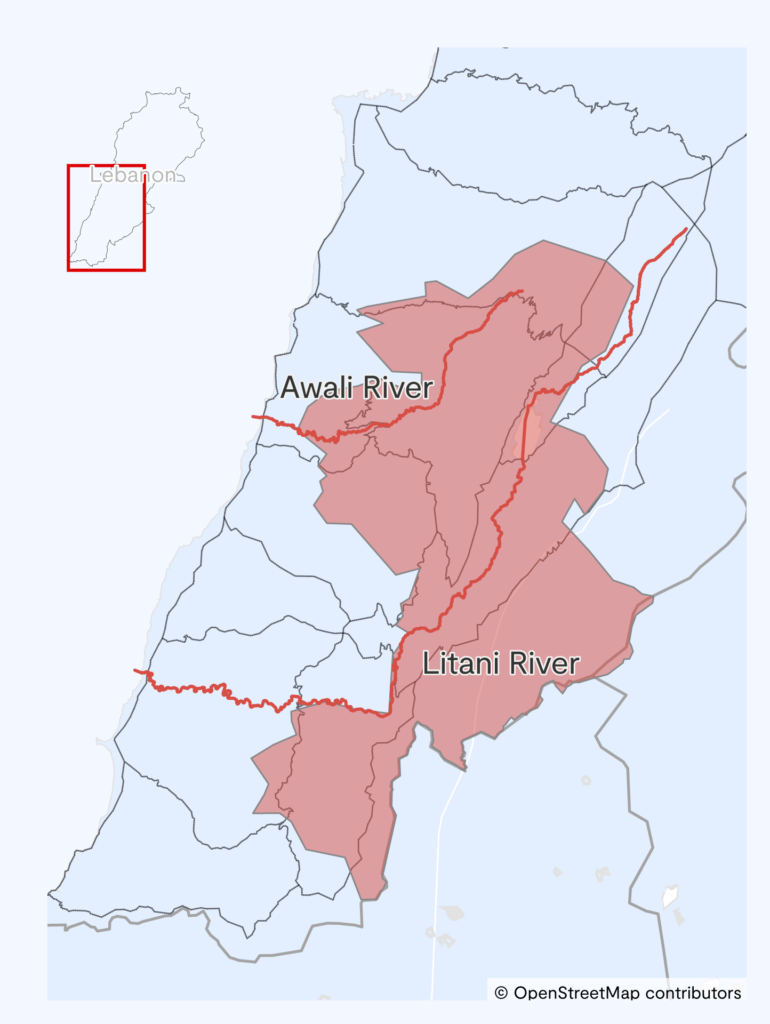

In January 2022, a series of police raids disrupted the early morning peace of several villages in Lebanon’s mountainous Chouf region. Conducted in cooperation with the Litani River Authority (LRA), a regional utility responsible for generating much of the area’s electricity, the target of the raids was crypto miners. So many of them had set up in the Chouf that they had started to destabilize the local grid.

The reason that the miners had congregated in the idyllic Chouf region was simple: electricity. The specialized computers that miners use require large amounts of power to run and, at least on paper, Lebanon has some of the cheapest electricity in the world. Today, however, that fact is largely academic. After decades of what the World Bank has called “colossal failures,” and two years of hyperinflation, the state-owned power supplier Électricité du Liban (EDL) has collapsed, and little electricity is generated or delivered in most of the country. Those who can afford it pay a subscription to an expensive, privately run diesel generator. Those who can’t must live with rolling blackouts of more than 20 hours a day.

Except, that is, in the Chouf. Here, as part of a mandate which also includes irrigation, drinking water provision, and local economic development around its namesake river, the LRA runs three antiquated hydro-power stations. These provide 20 hours of electricity per day to around 200 villages in the vicinity. That has made the Chouf an anomaly in an otherwise electricity-starved Lebanon — and a veritable magnet for crypto miners.

This unlikely cottage industry of miners continues to find razor-thin niches of profitability in Lebanon’s crumbling infrastructure. At times, their operations put them into direct competition with local residents as they extract scant resources from a system already in collapse. The depth of Lebanon’s socioeconomic decay means that the state has struggled to come up with a coherent centralized response to this new industry. Individual communities are left to deal with the miners themselves. As a result, the miners are exposing how — just like the grid — Lebanon’s crisis is breaking down centralized government power.

In October 2019, decades of entrenched corruption in Lebanon came to a head. Mass anti-government protests erupted, and soon after, the Lebanese lira essentially lost its dollar peg, and living standards collapsed. Salaries and savings held in Lebanese lira became practically worthless. Deposits in U.S. dollars were trapped in banks that imposed extreme capital controls and literally covered their branches in steel plating. As the banking system disintegrated, many Lebanese turned to stablecoins — cryptocurrencies with fixed values — to move funds in and out of the country. Some even managed to recover lost deposits through speculation and investment in the cryptocurrency markets. Many also turned to mining as a means of obtaining a dollar-denominated income.

The investment cost and technical barriers to mining mean that most of the cryptocurrency mining done around the world is handled by large companies that concentrate hardware in facilities located near sources of cheap energy. In the U.S., relatively low-cost industrial electricity rates, a deregulated energy market, and significant renewable energy sources have attracted large concentrations of large-scale cryptocurrency mining operations in places like Texas and the Pacific Northwest.https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/35U2R/1/

Crypto stress

The top three concerns of crypto miners in Lebanon.

Energy cost : 26%

Cryptocurrency price volatility: 22%

Equipment/hardware theft: 11%

Wallet theft/hacking : 9%

Inaccessibility of hardware/computer equipment: 7%

Other: 2%

Based on a survey of 71 miners in Lebanon conducted by Rest of World in July 2022.Chart: Rest of World Source: Adam Hasan

But, in Lebanon, the industry is more analogous to artisanal mineral mining. Individuals or small groups of people invest in a few machines and seek out pockets of consistent electricity supply, legal or otherwise. A survey of 71 Lebanese miners conducted by Rest of World in July 2022 indicated that over two-thirds of respondents own fewer than ten rigs. Almost half of those surveyed take part in “mining farms” — dedicated spaces where, in return for a fee, groups of miners co-locate their machines and pool resources to ensure hardware security, consistent power, and cooling.

Despite the barriers to entry and the slim profits available to small-scale miners, necessity and word of mouth drove Lebanon’s crypto-mining community.

“Mining is important here because there are simply no jobs,” Rawad el Hajj, who runs seven mining machines in the Chouf, told Rest of World. In a country as poor, small, and interconnected as Lebanon, each successful miner inspires others to overcome their skepticism. “My father was against it at first,” said Rawad. “He didn’t believe a machine could make money. Now he checks up on them more than me.”

When mining initially gained traction in early 2020, the Lebanese grid was still able to provide around 18 hours of power per day. Fuel was subsidized by the government so most miners connected to the grid and plugged the gaps with a generator subscription.

This did not last for long, though. Ghassan Gibran, the LRA’s head of hydropower, told Rest of World that in order for Lebanon to provide electricity to all of its residents around-the-clock, the country needs 3,000 megawatts. EDL currently generates just a tenth of that: 300 megawatts. As a result, most households across the country typically only receive 1-2 hours per day of power. Many get none at all.

As blackouts increased and fuel subsidies were lifted throughout 2020 and into 2021, mining became unviable across most of the country. Many miners sold their hardware, often at a loss. Those who had invested significant capital looked around for other options. Rising fuel prices meant that even mining farms, where fuel costs were shared, were barely profitable. For those unwilling to sacrifice so much of their profit margins, the LRA’s three hydro plants — and the cheap energy they produced — made the previously unremarkable villages of the Chouf irresistible.

It is practically impossible to know how many miners descended on the Chouf during late 2020 and 2021 but the number is estimated to be in the high hundreds. According to the LRA, by the end of 2021, there was a 20% surge in electricity demand in the region, resulting in increasingly frequent power outages throughout many of the Chouf’s villages. Officials blamed the outages on the “cryptocurrency mafia.”

As Lebanon’s electricity grid broke down, so did the state’s centralized authority. That means the official response to the influx of miners across the LRA’s service area has been erratic, illustrating the way in which communities are being left on their own to solve problems.

Perched on top of a steep escarpment with sweeping views across a valley of pine and apple orchards, Jezzine is the largest settlement to benefit from the LRA’s hydropower. A village of around three thousand residents, it was a well-to-do place with a buzzing tourist industry just a few years ago. Now, it survives on remittances sent back by the many inhabitants who have moved abroad.

For Jezzine’s municipal government, the miners were nothing but a nuisance. “The miners started to arrive in summer 2021,” Samer Aoun, the municipality’s deputy president, told Rest of World. “By September, we knew that it was a problem because of over-capacity and outages.”

As residents complained about Jezzine’s grid going down more frequently, the municipality turned to Beirut. “We asked for a legal study into what could be done and the financial prosecutor took the decision to shut it down on the grounds of unpaid import taxes on the hardware,” said Aoun. The plea led to police raids early the following year. In Jezzine, the raids appear to have forced out the majority of miners. Since then, officials say that the electrical grid has regained stability. Miners who Rest of World spoke to in Jezzine all claimed to have shut down or moved their operations.

In nearby Zaarourieh, a sleepy town in the Chouf located approximately 30 kilometers north-west of Jezzine, police raids on the mining operations had the opposite effect. Resident Ahmed Abu Daher had already been mining for a couple of years when the police came. The 22-year-old architecture graduate had installed mining rigs in around 10 different properties around Zaarourieh. He saw the potential in his town’s supply of ultra-cheap, near-constant electricity, and he harbored bigger ambitions. The raids offered him an opening to start expanding further.

“During that first visit from the LRA and the police, I made some contacts with the LRA guys,” he told Rest of World. After the authorities left, Abu Daher enlisted the help of an electrical engineer to survey Zaarourieh’s transformers, a critical piece of electrical infrastructure that steps voltage down from long-distance transmission lines into lower voltages that are safe for homes and businesses. “Then, I went to them with a plan showing which transformers still have some spare capacity and which don’t.”

Across the region, the raids did little to put off miners seeking cheap and ample electricity. Abu Daher positioned himself as a middleman between miners and the local residents. He approached residents of Zaarourieh who had space in their properties, and proposed refitting them to house rigs. In return, the property owner could choose between receiving either a flat monthly fee or a percentage share of the mined coins from the owner of the hardware. By conducting technical surveys and connecting mining equipment to underutilized transformers, Abu Daher stayed below power thresholds that would otherwise compromise Zaarourieh’s grid. This, combined with the LRA contacts he had made, allowed him to expand his operation without antagonizing the utility or his community.

For many of the miners who spoke to Rest of World, coming to the Chouf was a simple act of self-interest. They needed power to make money — and there was power in the Chouf. Abu Daher protected his operation by giving much of the community a stake in it. Residents received rent from the miners and he commissioned local engineers to install the circuitry, cooling systems, and sound-proofing. “The most important thing I did was to make the village the beneficiary,” he said.

Abu Daher claims that he’s helped install up to 3,000 machines in Zaarourieh and the surrounding area, although he says that this number has since come down as miners have upgraded to more efficient machines. Rest of World saw several installations, each housing from three to 15 mining machines in a variety of locations including half-built properties, a shuttered barber shop, and private homes. In one location just outside of Zaarourieh, which Rest of World was asked not to reveal for reasons of security, Abu Daher’s team was in the process of converting an outhouse on a private residential property into a farm set to house 30 of the most powerful rigs currently available.

The brick structure had been fitted with a complex cooling system, sound-proofing, and electronics, all of which could be controlled remotely. A farm of that size required far more power than the local transformer could provide, so Abu Daher approached the LRA and requested that they install a transformer on the property. Although businesses with a high electricity demand can request a dedicated transformer from the LRA, he was told that there were none left and there was no budget to buy more. Undeterred, he purchased the transformer himself at a cost of $15,000 and negotiated with local LRA agents to have it installed on the property. He has since completed this quasi-formal process in five other locations.

As far as Abu Daher is concerned, the miners who got kicked out of Jezzine fell victim to their own technical clumsiness. “The problem in Jezzine was that nobody bothered to understand where and how to set up. A lot of locations can’t even take another 5 amps without damaging the line. Other [transformers] can give another 200 amps.”

In Jezzine, Aoun has a different take. The Chouf, like much of Lebanon, is a culturally mixed region governed by diverse political actors, not all of whom are deferential to Beirut. “The problem is we were the only village that cooperated with the authorities,” explained Aoun. “In the surrounding areas, local leaders are too strong and won’t tolerate the authorities confiscating assets from their followers.”

Jacob Russell is a photographer and journalist based between Lebanon and France.

Adam Hasan is a geographer and PhD student at the University of California, Berkeley.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.