No American head of state has refused to relinquish power at term’s end—even in a contested election. Here’s why it’s unlikely to happen now.

BY AMY MCKEEVER

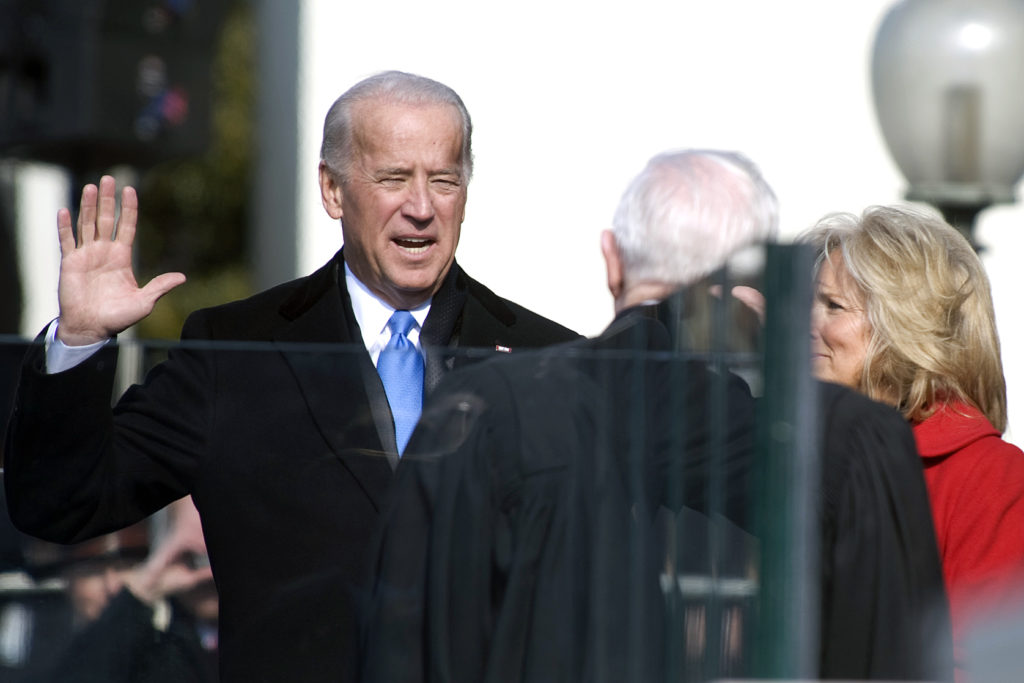

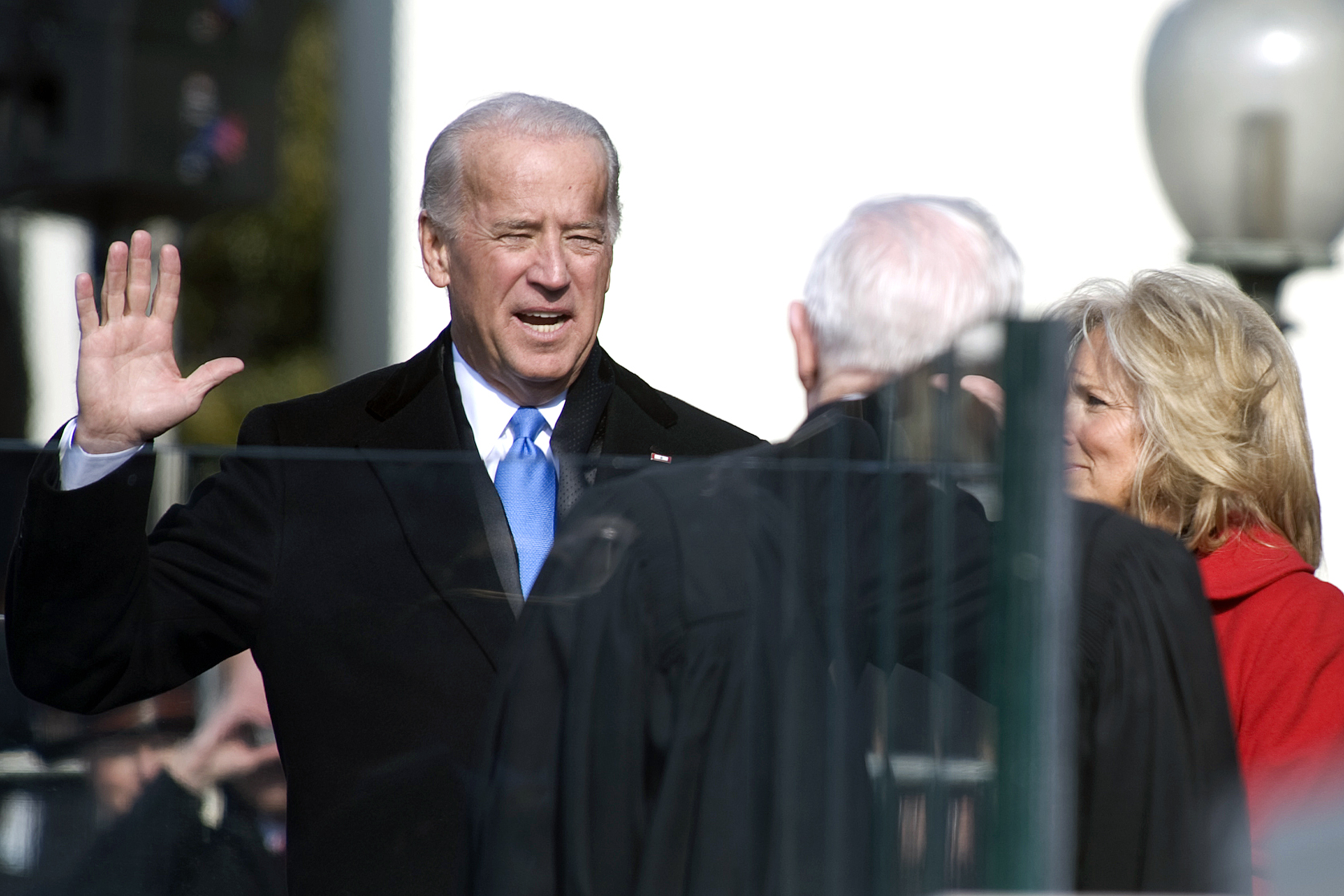

IN THE TIME since the U.S. presidential election was called in favor of former Vice President Joe Biden, President Donald Trump’s words and actions have raised fears among some observers that he might refuse to relinquish power. Constitutional law scholars say there are protections in place to ensure that every president must leave office when his or her term is up—and if those protections were to fail, the country would be facing a much bigger, constitutional crisis.

Although the electoral certification process technically is still ongoing, Biden has emerged the clear winner from the state-by-state vote tallies. Every candidate in modern elections who lost by this wide a margin had conceded by this point. (Formal concessions didn’t become an election custom until 1896, when Republican William McKinley defeated Democrat William Jennings Bryan.)

Trump has so far refused to concede, and his campaign has filed more than a dozen lawsuits in several key battleground states while making unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud; many of the suits are based on such thin evidence that they have already been dismissed.

While a defeated president’s refusal to step down would be unprecedented in American history, anxiety over how to keep a president’s power in check dates as far back as the 1787 Constitutional Convention. “That was a source of tremendous discussion and concern,” says Rick Pildes, professor of constitutional law at the New York University School of Law.

“But I don’t think that [the framers] talked about or even imagined the possibility that a president would somehow try to stay in office beyond their term,” Pildes says, and as a result, the Constitution doesn’t specifically address such a scenario. But it does protect against it.

During any president’s term, there are two avenues for removing them from office—impeachment and the 25th Amendment, which allows lawmakers to remove a president who is sick or otherwise unable to fulfill his or her duties. Neither of these would apply if someone tried to overstay their term, because that person would no longer be president; U.S. presidents are limited under the Constitution to four-year terms that end on January 20 after an election year. Here’s why Constitutional provisions about transfer of power matter—and how it would apply this year.

A four-year term with a hard end date

The length of the presidential term was the subject of vigorous debate at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Some delegates advocated for the presidency to last for three years, while others favored a seven-year term. Alexander Hamilton—an ardent Federalist who believed in a strong, centralized government—even pushed for a lifetime term.

Hamilton’s idea was shot down by the rest of the delegates, who were loath to recreate a system similar to the lifetime monarchy against which they had just rebelled. In his notes from the convention, James Madison describedHamilton’s suggestion as the equivalent of an “elective Monarch.”

Ultimately, the delegates compromised on a term of four years, enshrined in Article II, Section I of the Constitution. Hamilton went to bat for the idea in the Federalist Papers, a series of essays intended to persuade the states to ratify the Constitution, arguing that four years was just enough time for a president to make a difference—and that the possibility of reelection would encourage “good behavior” in a president who would need public support to stay in office.

A U.S. president’s term technically ends on Inauguration Day. For more than a century, presidential inaugurations took place in March, before they were moved to January 20 with the 1933 ratification of the 20th Amendment, which states that the president and vice president’s terms “shall end at noon” on that day. Even if a president is reelected, there’s a clear line between his first and second term. And ever since George Washington, reelected presidents have re-taken the oath of office on Inauguration Day.

What that means for 2021

On January 20, 2021, the winner of the 2020 election will be sworn in. And though the states are still certifying their counts, and the Electoral College will meet on December 14 to formalize the result, experts say that Biden’s victory is clear, with 79.5 million of the votes cast compared with Trump’s 73.6 million, and a comfortable margin of electoral votes.

“I think the decisiveness of Biden’s victory [is] substantial enough to withstand any kind of recounts,” says Lawrence Douglas, a professor of law, jurisprudence, and social thought at Amherst College and author of Will He Go? In his book, Douglas gamed out scenarios in which Trump could hold onto power in a closely contested election.

Douglas doesn’t believe any of those scenarios are likely now, noting that recounts typically may change results by a few hundred votes, whereas Biden is ahead by thousands or tens of thousands of votes in each of the battleground states. The lawsuits, he says, “are really meritless and frivolous, without any kind of realistic prospect of having any impact on the election.” Even if some Republicans in Congress were to raise objections on January 6—when the body will count Electoral College votes and formally declare a winner—Douglas doesn’t think they’ll gain any traction.

When Biden is sworn into the presidency on Inauguration Day, Trump will become a civilian. If Trump attempted to remain, Biden would have the authority as the new commander in chief to order the military or Secret Service to physically remove Trump from the premises. “The current president’s term ends, period,” on Inauguration Day, Pildes says. Trump “would be a trespasser at that point.”

What happens if the election is still contested

In the unlikely event that the results of any presidential election were still contested on Inauguration Day, Congress would be tasked to sort out the mess, and an acting president would step in temporarily under the Presidential Succession Act.

In 1792, the first Presidential Succession Act named the president pro tempore of the Senate as the first in line of succession if there were no president or vice president due to “death, resignation, removal from office, inability, or failure to qualify.” In 1886, Congress moved the secretary of state to the front of the line.

In 1947, Harry Truman signed the Presidential Succession Act that stands today: Now, the speaker of the House is first in line for the presidency, followed by the president pro tempore of the Senate and the members of the Cabinet in order of when their department was established.

The Presidential Succession Act has never been invoked—and Douglas says it’s almost inconceivable it would be relevant on Inauguration Day.

The importance of norms

“I don’t imagine Trump ever conceding, but I do imagine him submitting to defeat,” Douglas says. The distinction is key, he says; Trump is likely to continue to claim victory even after leaving office so as to keep a strong connection to his supporters—and potentially stage a comeback in 2024.

But why aren’t there any specific measures in place to prevent any president from staying past his or her term? Pildes argues that this ambiguity does not imply a failure of the legal system that the framers put in place.

“This has never happened in the entire history of the United States, so they weren’t wrong not to think this was a likely scenario,” he says.

Douglas agrees, noting that every legal system relies on a system of norms—such as conceding defeat and the peaceful transition of power—in order to exist. If enough people stop buying into those norms, it can corrode the system.

“Constitutional democracy assumes that people have faith in the integrity of the electoral process and can trust the outcomes,” Douglas says. “If they have the president himself—not some marginal fringe group—telling the people that the system is rigged and the results can’t be trusted, it’s an incredibly dangerous message to spread.”

National Geographic

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.