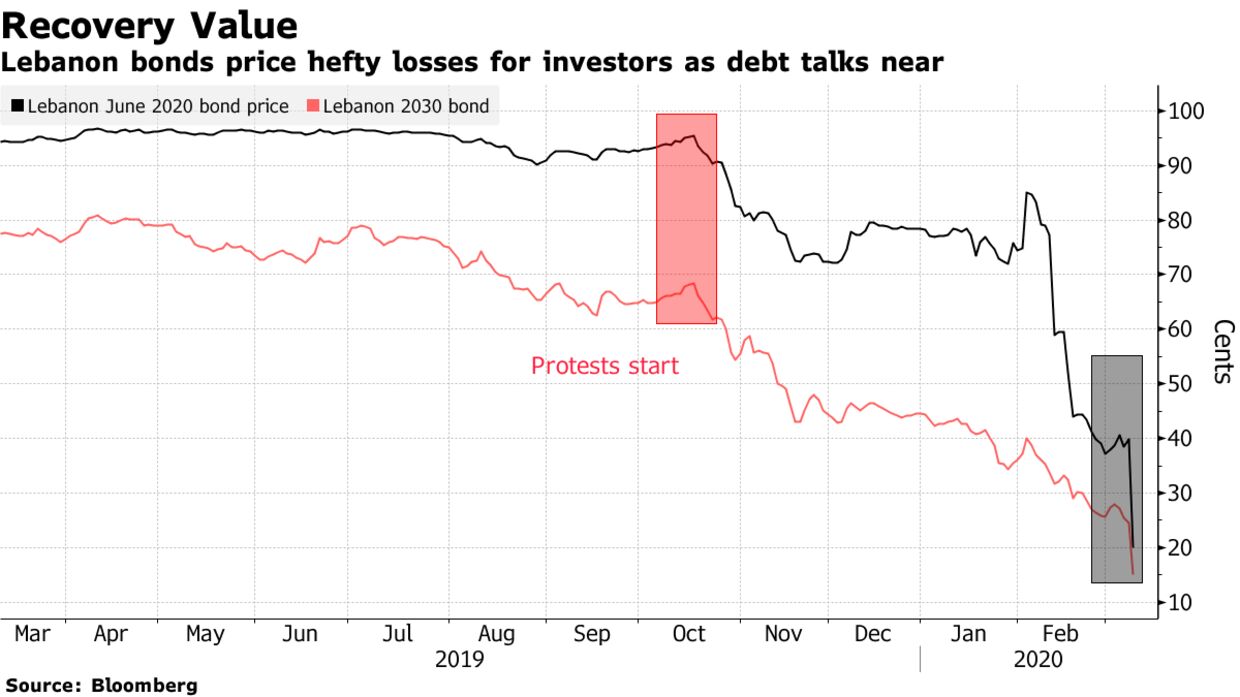

Lebanon is waiting to see if foreign bondholders will agree to negotiate new terms on more than $30 billion of debt as the government attempts to contain the country’s worst financial meltdown amid tightening liquidity.

The Middle Eastern nation is looking to cut its debt load from 170% of gross domestic product by defaulting on bonds and setting new parameters with creditors.

Local banks, the largest holders of Eurobonds, have agreed to start talks on a restructuring, and hired Houlihan Lokey Inc. as advisers. Now Lebanon is hoping foreign investors will also join the negotiating table, and contribute to the voting majority needed to change terms on bonds.

That would help avoid a messy default and the lengthy court battles that kept Argentina away from international credit markets for years.

“They have two options: negotiate as we have said in good faith and as fairly as possible, or take the legal route. It’s up to them.” Economy Minister Raoul Nehme told Bloomberg.

Lebanon’s declaration puts the country on course for the first default in its history as it copes with dwindling foreign-currency reserves and inflation running in double digits.

Bonds added to recent declines on Monday, pricing in losses of about 80% of face value on most maturities. Fitch Ratings cut Lebanon’s credit score to C from CC, reflecting an imminent default.

The government said it will prioritize using the $22 billion in available foreign-currency reserves to pay for the import of essential goods, as opposed to paying back a $1.2 billion bond that fell due on Monday.

In its reform program, the government will seek to more than halve debt to between 60% and 80% of output, Nehme said.

Lebanon’s economy has came undone after months of protests fed its worst financial crisis in decades, with remittances from abroad — the main source of hard-currency revenue — slowing to a trickle. Led by a new government backed by Hezbollah and its allies, one of the world’s most indebted nations will be taking on creditors at a time the global economy is reeling from the coronavirus outbreak and the start of an oil-price war.

It’s uncertain how much appetite foreign investors will have to offer debt relief against such a backdrop.

Ashmore Group Plc, has amassed a blocking stake in the $1.2 billion March bond, as well as last positions in the $1.3 billion of notes maturing in April and June. Spokesman Jan Dehn declined to comment on the company’s plans.

Creditors have started opening lines of communications with Lebanon, said Hans Humes, the chief executive of New York-based distressed-debt investor Greylock Capital Management, which has formed a group with other bondholders.

IMF, Hezbollah

With Lebanese authorities rushing to compile a credible overhaul plan, it wasn’t clear whether the restructuring would be part of a request for an International Monetary Fund bailout. Although IMF experts recently held meetings in Beirut, the issue of securing financing from the fund has become entangled in politics.

Hezbollah, an Iran-backed group that has a major say in government and parliament, has rejected the possibility of seeking a financial aid program from the IMF, fearing it could hurt the poor and be used by the U.S. as a political lever. That deprives Lebanon of a potential lifeline and could undermine the confidence in economic reform that creditors need when forgiving debt.

Iran and the U.S. came to the brink of war earlier this year, with the Trump administration imposing punishing sanctions on the Islamic Republic after abandoning the 2015 nuclear deal.

“The IMF involvement will be tricky given the current U.S. policies,” said Humes at Greylock Capital. “There is no question that the heightened tension between U.S. and Iran has complicated the situation in this and many other ways.”

Currency Devaluation

Another question is how Lebanon will deal with a parallel currency market, that’s mushroomed as the central bank set limits on access to dollars. Unofficial rates are pricing a devaluation of more than 40% for the Lebanese pound, which has been pegged to the dollar since 1997.

Even if the Eurobonds were restructured with a writedown, any devaluation in the official exchange rate would likely keep the overall debt burden high. The economy minister said any change to the peg would depend on plans the government is still working on.

“Ideally, we’d like to keep the peg to protect the purchasing power of the Lebanese people,” Nehme said.

BLOOMBERG

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.