By Abeer Abu Omar and Dana Khraiche

Downtown Beirut often resembles a ghost town these days. When it does get busy, it’s usually because anti-government protesters have gathered, chanting slogans such as: “Eat the rich!”

One of the targets of their anger has been Solidere, which rebuilt that part of Lebanon’s capital after a devastating civil war ended thirty years ago.

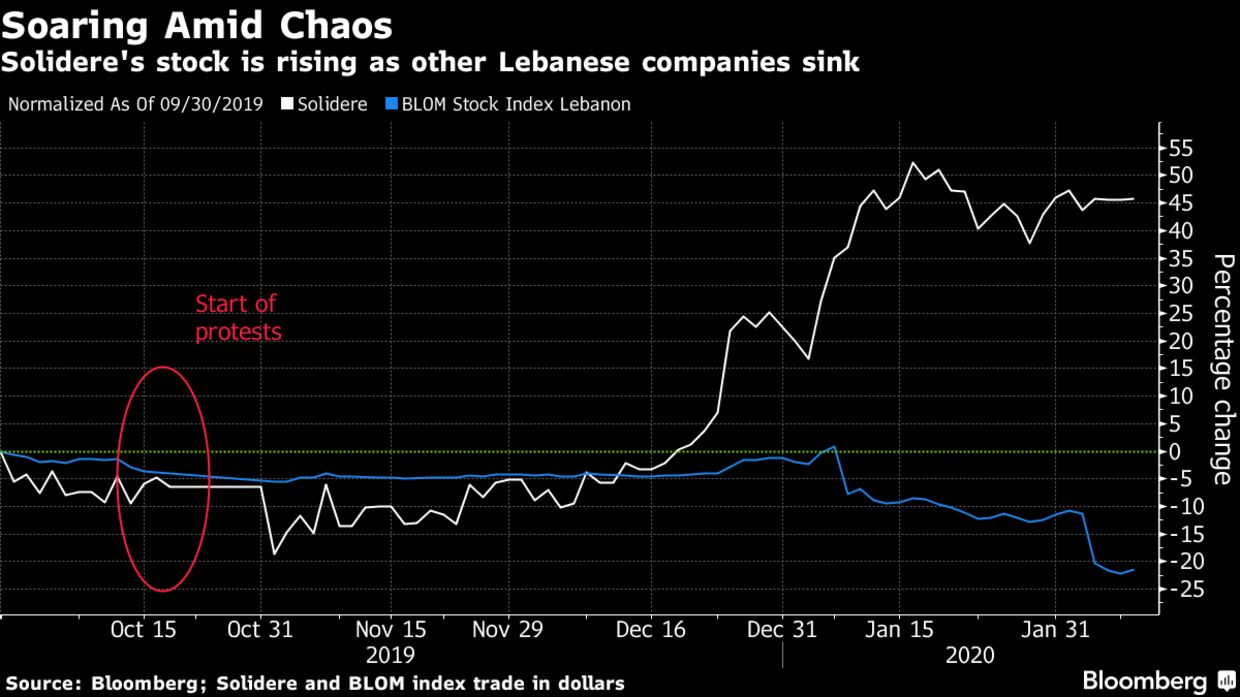

Yet the company’s shares have soared since the demonstrators first took to the streets in October, even as the rest of the stock market sinks, the local currency tumbles on the black market and the cash-strapped government weighs defaulting on its Eurobonds.

Once a bellwether for political stability in the Middle Eastern country, Solidere’s surge now reflects the desperation of Lebanese as the economy unravels.

They’re scrambling to protect their savings from potential banking collapses or their dollar deposits from being converted into Lebanese pounds if the foreign-exchange squeeze gets more acute. Real estate and Solidere shares, which trade in dollars, are suddenly popular.

“You have a new class of investors,” said Faysal Barbir, head of fixed income at FFA Private Bank in Beirut. “These investors were bank depositors that are now looking to diversify, and they have very limited options.”

Solidere’s main shares have climbed 46% since touching a 15-year low in October, giving it a market valuation of $1.4 billion, the biggest in Lebanon. Over the same period the country’s equity gauge, the Blom Stock Index, has lost 21%, the most in the world.

The protesters — many of them young and jobless — accuse the company of gentrifying central Beirut, which is filled with luxury shops such as Louis Vuitton, Hermes and Rolex, and pushing out working-class people. At least until the troubles started, two-bed flats overlooking a marina Solidere built would sell for more than $1 million. Carlos Ghosn, the former chief executive of Nissan Motor Co. and now international fugitive, lives barely a mile away.

The company’s closely connected to the political establishment. It was founded by billionaire and then-Prime Minister Rafic Hariri. He was assassinated with a car bomb in 2005 in central Beirut. His son, Saad, also led a government, until the protests forced him to step down.

Getting Scared

Despite Solidere’s unpopularity, it is seen as a safe bet compared to other stocks such as banks.

Local lenders are under increasing strain. They’ve restricted customers’ ability to withdraw dollars and transfer money abroad. The government’s pressured them into lowering the interest rates they get on some sovereign bonds. Their shares are among the worst performers on the Lebanese bourse this year — BLOM Bank SAL and Bank Audi SAL are each down more than 40%.

Solidere made a $42 million profit in the first half of 2019, its most recent financial statements show, compared with a loss of almost $100 million a year earlier.

“We are seeing quite a bit of demand on land,” said Ghazi Youssef, a Solidere board member and former lawmaker. “A lot of people are trying to park their money in real estate.”

Still, Solidere’s hardly immune from Lebanon’s economic strife. Its return to profit was mostly down to a decision to increase land sales to repay bank loans. It hasn’t paid a dividend to shareholders in more than five years, though it plans to do so again in 2021, Youssef said.

For now, though, it’s about the only choice for Lebanese with money to spare.

“People are getting scared,” said Raja Makarem, chief executive of Ramco, a real estate advisory firm in Beirut. “Some people are rushing out of the banking system to go to real estate, thinking this will be a good temporary shelter for them until things get better.”

BLOOMBERG

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.