RIYADH: His eyes brimming with tears, a Uighur student in Saudi Arabia holds out his Chinese passport – long past its expiry date and condemning him to an uncertain fate as the kingdom grows closer to Beijing.

The Chinese mission in Saudi Arabia stopped renewing passports for the ethnic Muslim minority more than two years ago, in what campaigners call a pressure tactic exercised in many countries to force the Uighur diaspora to return home.Advertisement

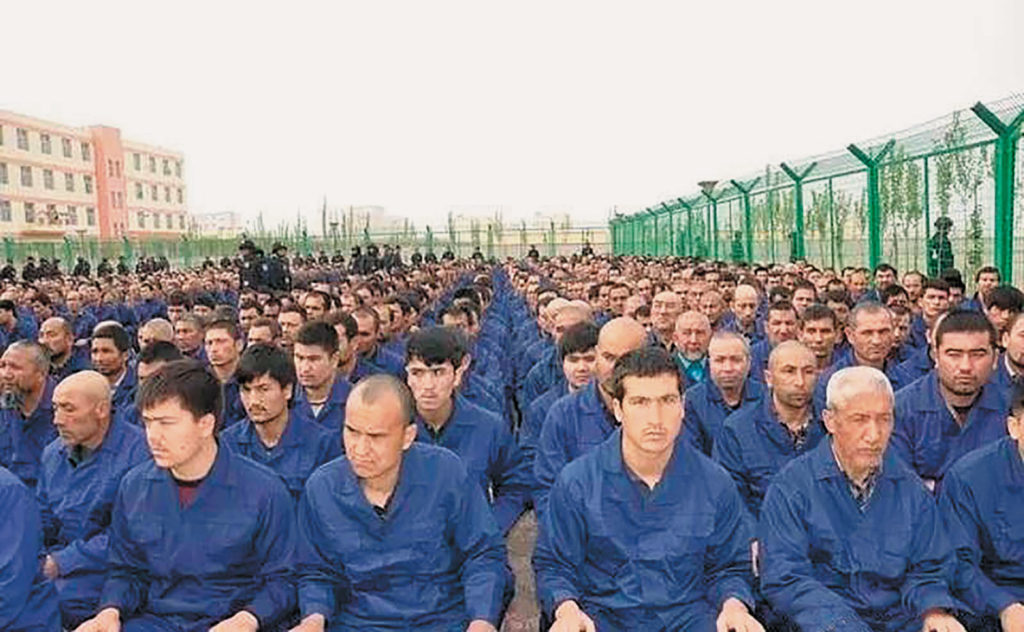

Half a dozen Uighur families in Saudi Arabia who showed AFP their passports – a few already expired and some approaching the date – said they dread going back to China, where over a million Uighurs are believed to be held in internment camps.

“Even animals in other countries are allowed to have passports,” said the 30-year-old religious student in the Muslim holy city of Medina, whose passport expired in 2018.

“Either they should renew my passport or let me drop my nationality. They make us feel like worthless humans.”

The community, now offered a one-way travel document suitable only for a trip to China, faces an impossible choice: return home at the risk of detention or remain illegally in the kingdom under constant fear of deportation.

“Refusing passport renewals is part of China’s strategy to smoke out the Uighur diaspora, forcing them to return to China,” Norway-based Uighur linguist Abduweli Ayup told AFP.

“What awaits them on the other side is detention.”

Amplifying the community’s fears is the conspicuous silence of Muslim-majority states – from Pakistan to Egypt – over China’s treatment of Uighurs as they avoid crossing Beijing, an economic powerhouse.

Particularly concerning is Beijing’s deepening ties with Saudi Arabia – the epicentre of the Muslim world and home to Islam’s two holiest sites – which has reportedly condoned the Uighur policy of China, the top importer of Saudi oil.

Saudi Arabia supports “China’s rights to take counter-terrorism and de-extremism” measures, Chinese state media quoted Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman as saying last year.

This year, China threw its support behind the kingdom over its handling of journalist Jamal Khashoggi’s murder trial, which triggered global criticism after Prince Mohammed’s closest aides were absolved of blame.

‘UNTRACEABLE’

Only a few hundred Uighurs are estimated to be in Saudi Arabia, a disenfranchised community of mainly seminary students, traders and asylum seekers, many cut off from their detained families in China.

Many are wary of what they suspect are Chinese spies and some are forced to live in hiding, a Uighur businessman in the kingdom said, showing AFP copies of eight expired passports of fellow Uighurs that have rendered them illegal.

“Within the next two years, expect many more Uighurs to become stateless,” he said.

Many have fled while they can, often heading to Turkey or Sweden.

A Uighur student in the kingdom told AFP that three of his friends deported since late 2016 have become “untraceable” after arriving in China, likely now in the so-called re-education camps that Beijing says are meant to counter extremism.

Ayup told AFP he had confirmed five deportation cases from Saudi Arabia since 2017. Other Uighur campaigners say the number is higher. Similar extraditions have been reported from Egypt and Thailand.

It is unclear whether Riyadh carried out deportations under pressure from China or if they were swept up in the kingdom’s broad crackdown on illegal expatriates. Saudi officials did not respond to requests for comment.

The Chinese embassy in Riyadh told AFP it does not “cooperate with Saudi authorities to deport Uighurs”.

When asked about their refusal to renew passports, it only said it had not stopped consular services for their Uighur “brothers and sisters”.

Multiple members of the ethnic minority said they feared visiting the Chinese mission in the kingdom as some had had their passports invalidated even before the expiry date.

‘WE FEEL HELPLESS’

In a letter sent last year to the Chinese consulate in the western city of Jeddah, a group of Uighur students asked why it was renewing passports for the ethnic Han community in the kingdom while ignoring their requests.

“We are from the same country,” said the letter seen by AFP.

“For two years we haven’t been able to contact our fathers, mothers and brothers in China… We have heard they are imprisoned because of our study in Saudi Arabia.”

Chinese authorities target Uighurs with links to 26 “sensitive” countries, including Saudi Arabia, on the grounds they were prone to “extremist thought”, several campaigners said citing government documents.

Uighurs with connections to the Islamic kingdom are particularly vulnerable amid what observers call Beijing’s “anti-Saudisation” campaign to tackle influences that are blamed for introducing extremism in Chinese Islam.

“Greeting someone in Arabic, independent study of the Koran and even naming one’s son Mohammed or Saddam are all primary markers of extremism, which can result in detention or prison sentences for Uighurs,” Darren Byler, a University of Colorado researcher, told AFP.

The Uighur families deny any extremist links.

“I don’t want to get pregnant and bring a child into this world – the baby will get a blue document and a bleak future,” said one young Uighur woman, referring to the one-way travel permit

A new Human Rights Watch report reveals Chinese authorities use an app to track nearly every aspect of Uighurs’ lives and deem activities that have nothing to do with terrorism — keeping to oneself, using too much electricity, donating to a mosque — suspicious.

- “These dubious criteria are being used to identify large numbers of people, many of whom are then arbitrarily locked up,” says Sophie Richardson, china director for Human Rights Watch.

- Even those who aren’t locked up live under constant surveillance, as a recent NY Times interactive demonstrates.

The whole world is looking the other way

- Prime Minister Imran Khan of Pakistan, which borders Xinjiang but has a deep economic reliance on China, told the FT in March: “Frankly, I don’t know much about” what’s happening to the Uighurs.

- Indonesian President Joko Widodo gave a similar answer, despite leading the world’s largest majority-Muslim country.

- UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres appeared to tiptoe around the issue on a visit to China last week.

- Meanwhile the CEO of Volkswagen, which has a factory in Xinjiang, claimed last month that he was “not aware” of the mass detentions.

- The Organization of Islamic Cooperation went so far as to praise China in March for “providing care to its Muslim citizens,” while in February Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman defended China’s “right” to crack down on its Muslim citizens “for its national security.”

- The U.S. and EU have spoken out, as has Turkey, but as a Council on Foreign Relations report points out, “no country has taken action beyond issuing critical statements.”

- AFP/YL

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.