Former minister Hassan Diab, who has the backing of Hezbollah and its allies, gained enough votes from lawmakers on Thursday to be named Lebanon’s new prime minister.

The move to nominate Diab signaled a decision by Hezbollah and its allies to abandon efforts to forge a consensus with outgoing PM Saad Hariri and to install a candidate of their choosing, drawing on the parliamentary majority they secured in a 2018 election.

CRISIS

Lebanon is facing an unprecedented financial crisis: banks are imposing tight capital controls, the Lebanese pound has slumped by a third from its official rate and companies are shedding jobs and slashing salaries.

Fitch last week cut Lebanon’s credit rating for the third time in a year, warning it now expected the country to restructure or default on its debt.

Jason Tuvey, senior emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, said: “A government with a Hezbollah-backed prime minister would be even less likely to secure support from the Gulf countries…and might also potentially reduce the chances of Lebanon getting support from the IMF if the U.S. raises concerns.

“A senior banker said time is running out and that politicians do not grasp the scale of the crisis. He expressed concern Hezbollah is too preoccupied with its struggle with the United States. “Right now the real battle is how to solve this real crisis – liquidity meltdown,” the banker said.

Mohanad Hage Ali, a fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Center, said political tensions could lead to unrest between Shi’ite supporters of Hezbollah and Amal on the one hand, and Sunni supporters of Hariri on the other.

“The lack of Hariri support means that it is a polarizing government, which means it is less likely they will see (foreign) support,” he said.

Hariri had said he would only return as prime minister of a government of specialists which he believed would be able to secure Western support and satisfy protesters who have been demonstrating against rampant state corruption.

Hariri did not put forward anyone for the post of prime minister and MPs with his Future Movement told Aoun it would not take part in the next government, a source close to Hariri said.

Hariri had seemed on course to be nominated prime minister himself but withdrew his candidacy on Wednesday.

Former prime minister Mikati said Diab was not up to the job.”

I don’t want to deflate the hopes of Lebanese but I am skeptical that any of the proposed names could shoulder (the responsibility) during this period,” said Mikati, who had backed Hariri for the post.

Diab an electrical engineering professor at the American University of Beirut (AUB) was appointed as minister of education part of Mikati’s cabinet on 13 June 2011, replacing Hasan Mneimneh. Diab’s term ended on 15 February 2014 , months after Mikati’s government collapsed.

Mikati became premier in 2011 after Hezbollah and its partners brought down the unity government of Saad al-Hariri but resigned in March 2013 after a cabinet dispute with Hezbollah .

Diab’s failure to secure the backing of the main Sunni-led bloc could make it difficult to form a new government and secure Western aid, according to analysts.

After announcing Hezbollah’s support for Diab, Hezbollah lawmaker Mohammad Raad said the group had extended the hand of cooperation “for the sake of the country.”

News that Lebanon may finally get a new prime minister, nearly two months after the last one quit, is unlikely to end demonstrations that have wracked the country for weeks. The protesters, who have remained in the streets since bringing down the previous government, have made it abundantly clear they want to see the back of the entire political elite. They will not be impressed by Diab.

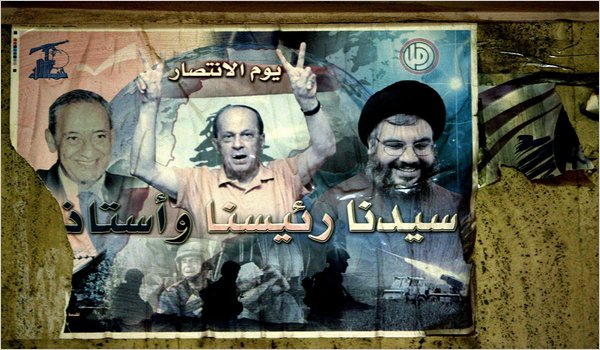

That Diab is backed by the two major Iran-backed Shiite factions, Hezbollah and Amal, will likely make him even less credible in the eyes of the protesters. Those two groups have in recent days been staging angry, raucous counter-protests, deliberately raising the specter of sectarian conflict in a country that bears the scars of previous such conflagrations.

Hezbollah, in particular, is desperate to protect the existing political order, one that maximizes its influence and minimizes its responsibility. No one stands to lose more from the sweeping reforms demanded by the protesters: a complete overhaul of the political system, undertaken by a government of unaffiliated technocrats.

This is anathema to Hezbollah and its allies, which have prospered from a political arrangement that apportions power along sectarian lines: the Maronite Christians have a lock on the presidency, the prime minister is always a Sunni, and the speaker of parliament is unfailingly Shiite. Any political reform that could change this cosy arrangement—and the rigid gerrymandering of parliament along communal lines—would threaten all sectarian parties. But Hezbollah is more likely than the others to resist such change with violence as the recent events have shown.

Lebanese alarmed

Lebanese are alarmed over what happened this week . On Monday, groups of Hezbollah and Amal supporters rampaged in the streets of Beirut, attacking protesters and fighting with security forces. This continued unabated for three days. They were supposedly enraged by a video by an allegedly drunk Sunni man insulting Shiites, but this was plainly pretext; such insults are hardly uncommon, and the response was aimed directly at the protest movement that threatens Hezbollah’s interests.

The counter-protests suggest the political stalemate between the demonstrators and the most determined protectors of the sectarian order is coming to a head. Hezbollah’s message is clear: if it needs to use violence to prevent real reforms in Lebanon, it will.

For many Lebanese, this message is a frightening reminder of the 1975-1990 civil war. The non-sectarian nature of the current protests had revived the ideal of Lebanon as a modern national project that would eventually transcend communal and confessional disparities and suspicions. That vision was never fully realized, but nonetheless prevailed in the national discourse until it was crushed by the civil war and replaced with the rigid and corrupt sectarian order that the protesters are now challenging.

AGENCIES/YL

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.