By Philip Jenkins

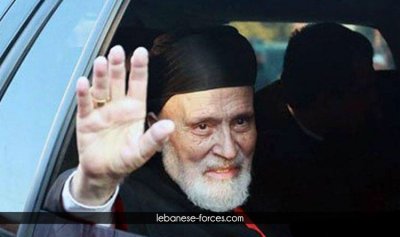

By Philip JenkinsThis past May, Lebanon’s Cardinal Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir died at the age of 98. Scarcely known outside his part of the world, he represented a link to the earliest Christian ages. Throughout his long life, he epitomized the modern struggle of Arab Christians to survive and flourish in a turbulent region. In a sense, his very name recapitulates that story, for it includes both the ancient name Boutros, the Arabic form of “Peter,” and the modern Arabic name Nasrallah, meaning “victory of God.”

Cardinal Sfeir presided over the Maronite Church, the largest Christian body in Lebanon, which takes its name from a venerated fourth-century hermit named Maroun. A long-standing joke attributes to his devotees the remark that “Yes, yes, God is great. But who is like St. Maroun?”

Although other churches dispute the claim, Sfeir claimed to be the legitimate Patriarch of Antioch, the 76th in a sequence going back to the original Boutros, St. Peter. The Maronites practice a liturgy that is Eastern and Syriac in origin, with a powerful monastic tradition and associated customs and dress. At the same time, they recognize the pope, and they are an autonomous or autocephalous community within the Roman Catholic Church.

In 1920, the very year of Sfeir’s birth, French diplomats were seeking to carve out territory from the wreckage of the Ottoman Empire. As part of their goal of protecting the region’s minorities, they took the part of Syria with the heaviest concentration of Maronites and demarcated it as the state of Greater Lebanon, a kind of reservation for Christians. This territory in the French mandate in effect was the beginning of the nation that would in the 1940s gain independence as the republic of Lebanon. The Maronites were prosperous, educated, and strongly Westernized, which led to Beirut claiming the title of the Paris of the Middle East.

The problem with the reservation approach was that the territory always included significant non-Christian minorities. In 1943 the different groups shared power and offices on the basis of a recent census, meaning that in theory the political balance of power was frozen in place according to the different groups’ relative strength in 1932. Maronites received the prize plums, followed by the Sunni Muslims and the Druze. All but ignored were the Shi’a Muslims, who were largely poor, rural, and uneducated.

That arrangement lasted until the 1970s, when the political accommodation was swamped by demography. As the number of Shi’a Muslims surged, they demanded their proper place in the country, and they allied with the well-armed Palestinian militants who had taken refuge there. From 1975 through 1990, an appalling civil war rent the country, killing perhaps 200,000. Maronites fled the country, moving to Europe, Australia, or North America, and today perhaps two-thirds of the world Maronite population of 4 million live outside the Near East.

Throughout Maronite history, church leaders have played a pivotal role in protecting the community. The country would not have come into existence in 1920 without the determined activism of then patriarch, Elias Peter Hoayek (another Peter). He is generally regarded as the father of the country of Lebanon.

Scarcely less important was Nasrallah Sfeir, who became patriarch in 1986. At a time when the Lebanese state had collapsed into multiple competing jurisdictions, he had simultaneously to maintain the concept of a united Lebanon and resist the pressure to submit to Syrian authority. He also had to speak for the good of his community, reduce violence, and call for social justice. The task was all but impossible, and several other key leaders of this time were assassinated or disappeared, generally through Syrian action.

Against that background, it is astonishing that Nasrallah Sfeir survived, never mind succeeding as well as he did. His limitless diplomatic skills allowed him to form close bonds with Sunni and Druze leaders, and he commanded the respect of his deadliest enemies on the Christian side. He continued to exercise that personal and spiritual authority into his nineties. (He resigned as patriarch in 2011.)

Hearing the story of a patriarch leading his people through such turmoil, we almost seem to be cast back to the days of the late Roman Empire. When Pope John Paul II made him a cardinal in 1994, he was acknowledging an epochal Christian life.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.