By : MITSURU OBE, Nikkei staff writer

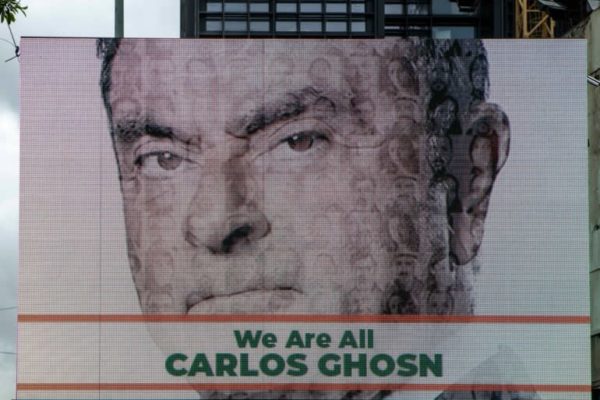

Nissan Motor is paying the price for having a board asleep at the switch, as prosecutors on Monday indicted the company and former Chairman Carlos Ghosn for allegedly under reporting his income for many years.

The main allegation against Ghosn is failing to report $44 million in compensation in Nissan’s financial statements over a period of five years. The amount includes tens of millions of dollars in deferred compensation he received but did not report when other Nissan executives reported their compensation in full in the financial statements.

“The board was clueless about something they should have known about, or it knew and was complicit,” said Jeffery Kingston, professor at Temple University in Japan. “In either case, the board did not do its job.”

Many experts are wondering why Nissan’s board did not take Ghosn to task before reporting to the authorities.

“This is essentially something that should have been resolved internally,” said Nicholas Benes, head of the Board Director Training Institute of Japan and a former investment banker. Benes is one of the architects of Japan’s corporate governance code, which was created in 2015.

The alleged under-reporting came to light following a tip-off from a whistleblower, prompting a secret internal probe within Nissan, and leading to Ghosn’s arrest by prosecutors.

There is no indication that other board members made actual moves in terms of governance processes or statements at the board level, Benes noted. This makes him suspect that the board members were more concerned about protecting their jobs than confronting the powerful CEO on their own. Ghosn was at the helm of Nissan for 18 years, having turned it around from the brink of bankruptcy.

If individual board members, including CEO Hiroto Saikawa, felt so strongly about the issue that they allowed a criminal investigation, they should have taken steps first, Benes said. These could have included proposing to discuss the issue at the board level, trying to call an extraordinary board meeting, threatening to resign or getting advice externally. No such internal moves appear to have been taken before the prosecutors’ move to arrest Ghosn.

Under Japanese company law, directors are expected to actively participate in discussions and oversee the chief executive.

“You have to do your duty as a director, regardless of the impact on yourself. The priority is the company, not you,” Benes said. “You have to be willing to do the right thing even if that means you will not be re-nominated or may have to step down.”

Admittedly, cultural and language barriers existed at the Nissan board, whose membership includes Japanese, French and and American. But Benes argues that such barriers are no excuse. “You cannot use that as an excuse at all,” he said.

With the prosecutors’ action, Nissan’s management is now held accountable for having done nothing to stop Ghosn’s alleged misdeeds. “All directors, including inside directors, need to be aware that if they passively acquiesce and permit malfeasance to go on even if they know about it, they also are violating their duty,” Benes stressed.

Nissan is not the only Japanese company where internal governance has failed to work. At Olympus, for instance, CEO Michael Woodford asked the board to investigate hidden losses in the company’s financial investments, only to be sacked by the board in 2011, prompting him to fight back by leaking information to the media. At Toshiba, the management didn’t come clean on billions of dollars in hidden losses in 2015 until a whistleblower tipped off the securities watchdog.

Pressure is already growing, from both the government and investors, on Japan Inc. to act on its governance weaknesses.

“Japanese companies should do more about corporate governance reform,” said Kerrie Waring, CEO at International Corporate Governance Network.

U.S. investment bank Jefferies has proposed making it mandatory for listed companies to have independent committees for auditing, executive nomination and executive compensation.

The Financial Services Agency is already moving to require listed companies to disclose the procedures for determining executive compensation, such as benchmarks on which executives’ performance is measured as well as performance-linked pay, in a bid to improve transparency and facilitate assessment by shareholders and other external parties.

Currently, listed companies are only required to disclose the names of executives whose compensation exceeds 100 million yen ($884,600) and the amounts they are paid.

Of the companies listed on the markets operated by Japan Exchange Group, including the Tokyo Stock Exchange, only 26% have an executive compensation committee. Nissan is not one of them.

There is a risk, however, that these rules will be followed only in form, rather than in spirit, adding to corporate bureaucracy without actually changing corporate performance. What matters, experts say, is to have directors who are willing to be seen as “troublemakers” and can raise awkward questions to the chief executives.

That means that educating directors will be just as important as setting up various oversight committees, ICGN’s Waring said.

Asia Nikkei

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.