Beirut, Lebanon – “Do you see the empty chair with a guitar next to it? Only the musician is missing.”

In the middle of her living room surrounded by dozens of paintings in her apartment in Haret Hreik, a suburb in Lebanon’s capital Beirut, Mariam Saidi describes her art, which is dedicated to her son.

“This one shows the Last Supper, but everything is broken,” she says.

On June 17, 1982, her 15-year-old son Maher Kassir left the house to go to school but never came back. It was the day Israeli troops reached Beirut, where a massive student protest was under way.

“I knew he was a communist sympathiser, but I was not aware he was also fighting with them,” Saidi says.

“When I asked the communist fighters where he was, they asked me to look for him. It’s been 36 years and I am still looking for my son.”

Landmark law

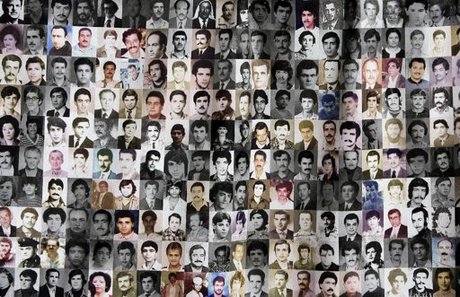

On Monday, following a divisive debate, the Lebanese parliament passed a landmark law to investigate the fate of thousands of people who have been missing since its 1975-1990 civil war, in which some 150,000 people died, and to hold those responsible to account.

The law sets up a national commission to find out what happened to those who were never found – an estimated 17,000 people, including collecting DNA samples from living family members and exhuming mass graves.

There are no public databases or exact numbers of people who went missing during the war, in which Muslims and Christians, who had lived side by side for centuries, retreated into separate enclaves controlled by sectarian militias.

Justine Di Mayo, co-president of the Act for the Disappeared NGO, called the law “a real turning point”.

Her organisation documents testimonies from former fighters and witnesses to the war to identify where mass graves could be located.

“For decades, politicians said we should not disturb the peace, or [said] bringing up the past would be a mistake. They were only convenient excuses for them,” she told Al Jazeera.

|

| Saidi’s son disappeared in 1982 when he was 15 [Virginie Le Borgne/Al Jazeera] |

An amnesty law was issued by the government in 1991 for crimes perpetrated before March 28, 1991.

“Several mass graves were destroyed because they were located on construction sites and there was no legal framework available on the issue,” said Di Mayo.

Another group, Committee of the Families of the Kidnapped and the Disappeared, was launched in 1982 by activist Wadad Halawani.

“We asked the families of those disappeared to meet and organise in order to put pressure on the politicians,” said Saidi, who is vice president of the group.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) called the passage of the latest law “a positive step for thousands of families to find closure”.

“So far, we have documented nearly 3,000 disappeared people,” said Jerome Thuet, who works for the Missing Project at the ICRC.

The ICRC is also collecting DNA samples of families with missing relatives.

“Once the commission will prove its transparency and show it is not discriminatory towards any particular group, we will share the samples with it,” Thuet told Al Jazeera.

Political rifts

There was no indication of when the commission would be formed, but Gebran Bassil, Lebanon’s foreign minister, said the country was entering a “genuine reconciliation phase” that would heal the families’ wounds.

Lebanon voted in May for its first new parliament in nine years.

With a long-entrenched political elite including local dynasties and former warlords, Prime Minister-designate Saad Hariri has yet to form a national unity government.

For families of the disappeared, there is still a long wait for closure.

“It is necessary to build a stable society which does not fall back to a cycle of violence,” said Di Mayo.

ALJAZEERA

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.