*By Ali al-Amin

Lebanon has been trying to form a new government since its general elections last May. Saad Hariri was appointed head of the new government and he must consult with Lebanon’s president to form his cabinet but that is not the only political force — domestic or regional — he must placate.

It’s been three months and the new cabinet is yet to see the light. Worse, it does not look like it will see the light any time soon.

The problem seems related to deciding on the quota of each political force in the cabinet. In this one, the deadlock centres on the so-called Druze knot, Christian knot and Sunni knot.

Observations of the government formation process in Lebanon during the past decade reveal that a crisis accompanied the birth of every cabinet. The past decade coincided with the rise of Iranian influence in Lebanon and of Hezbollah’s growing control on many state institutions.The resolution of these repetitive government crises required outside intervention. Usually, Iran would hold the crisis in Lebanon hostage until it gets what it wants regionally and internationally, then it would instruct Hezbollah to release the government in Lebanon.

A striking similarity exists between the government crises in Iraq and Lebanon. Strong disagreements about quotas seem to be blocking the process in each case. Iraq and Lebanon voted practically at the same time and in both elections victory was on the side of Iran and its allies.

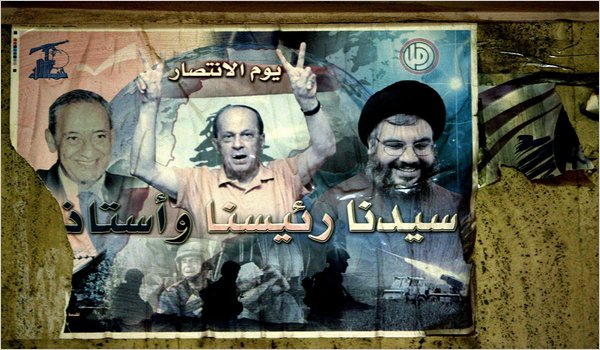

After the elections in Lebanon, Qassem Soleimani, commander of Iran’s al-Qud Force, happily announced that Hezbollah had secured 74 out of the 128 seats in parliament. He was referring to a political alliance between Hezbollah, the party of President Michel Aoun and the party of parliament Speaker Nabih Berri and other parliamentarians. In his mind, they’re all led by Hezbollah and therefore led by Iran.

Hezbollah seems capable of imposing its own version of the new government. Generally, Hezbollah gives great importance to regional considerations and objectives when battling for the composition of cabinet in Lebanon. This time, however, Hezbollah does not seem to be in a rush to decide. Like all the other parties involved, Hezbollah knows it controls the game.

If it wishes, Hezbollah can perpetuate the government crisis indefinitely. There is nothing in the constitution to prevent it. Hezbollah has solid experience at this game. From May 2014 through October 2016, Lebanon was without a president and Hezbollah was behind that crisis.

Knowing that, we need to ask about Iran’s objectives in delaying the government crises in Lebanon and Iraq. Iran has boasted about controlling four Arab capitals but it seems this control is subjected to serious challenges and threats.

In Yemen, the Houthis are losing ground to the “legitimate” forces and the Arab coalition forces. Changes in the Syrian scene do not seem to be going in Iran’s favour. Even though Syria’s future is vague, the Russian-US-Israeli entente does not look promising for Iran. Russia will have the last word there on condition that it curtails Iran’s influence in Syria.

The situation in Baghdad and Beirut is less catastrophic for Iran than in Sana’a and Damascus. Nevertheless, with US President Donald Trump’s anti-Iran crusade picking up momentum, the future for Iran’s influence in Iraq and Lebanon does not look rosy.

By raising the bar of anti-Iranian sanctions, Trump has virtually voided the nuclear agreement with Iran. The result is that any power or influence that Iran may continue to sway in Iraq and Lebanon is subject to great fluctuations due to strategic losses elsewhere in the Arab world.

The process of putting in place a new cabinet in Lebanon cannot be isolated from its regional context that Iran is continuously trying to shape and control. This time, however, the ransom for freeing the Lebanese government is not significant.

In Lebanon, Iran may seem to be holding enough cards to strike a deal with Israel; Iran would guarantee stability on Israel’s borders with Lebanon in exchange for Israel’s consent to Iran’s continued influence in Lebanon but even that scenario is contingent on the results of big changes in the region.

The process of putting in place a new cabinet in Lebanon cannot be isolated from its regional context that Iran is continuously trying to shape and control. This time, however, the ransom for freeing the Lebanese government is not significant.

Washington is not ready to compensate Hezbollah for its handy work of erecting hurdles in Lebanon and the European countries are not willing to meddle between Washington and Tehran. The Arab countries do not wish to pay for this get-out-of-jail card even though such a card has proved crucial for Iranian influence in Beirut.

What is holding up the formation of a new government in Lebanon is this quest for a buyer except that what Iran is offering for sale is no longer attractive to regional and international bidders.

*Ali al-Amin is a Lebanese writer.

The Arab Weekly

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.