President Trump has gone overseas to embark on some of the most consequential diplomatic negotiations of his tenure, threatening an all-out trade war with allies and seizing a chance to make peace with a nuclear-armed menace.

But back home, he left behind a West Wing where burned-out aides are eyeing the exits, as the mood in the White House is one of numbness and resignation that the president is growing only more emboldened to act on instinct alone.

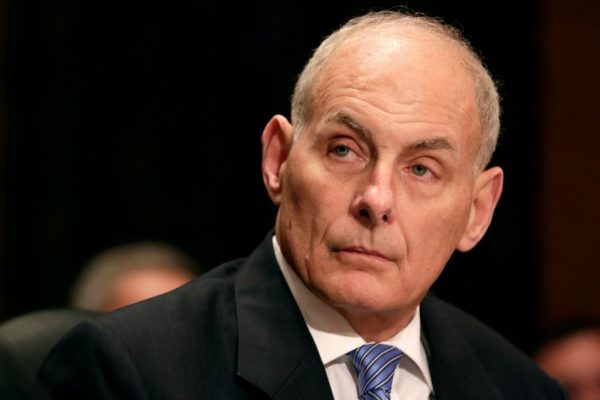

Mr. Trump, a former reality television star, may soon be working with a thinned-out cast in the middle of Season 2, well before the midterm elections. Several high-profile aides, including John F. Kelly, the president’s chief of staff, and Joe Hagin, a deputy of Mr. Kelly’s, are said to be thinking about how much longer they can stay. Last week, Mr. Kelly told visiting senators that the White House was “a miserable place to work,” according to a person with direct knowledge of the comment.

The turnover, which is expected to become an exodus after the November elections, does not worry the president, several people close to him said. He has grown comfortable with removing any barriers that might challenge him — including, in some cases, people who have the wrong chemistry or too frequently say no to him.

Mr. Trump, who desires a measure of chaos at all times, is reveling in the effects of his own mercurial decision-making, the people said.

Stephen K. Bannon, the president’s former chief strategist, said in an interview that Mr. Trump’s love of conflict had driven his approach to the presidency. “This is how he won,” Mr. Bannon said. “This is how he governs, and this is his ‘superpower.’ Drama, action, emotional power.”

Mr. Trump believes that he is gaining ground by trying to set the terms of news coverage around a number of issues affecting his White House, according to interviews with a dozen White House advisers, former aides and people close to the president. He has repeatedly promoted his performance at the one-year and 500-day milestones of his term, sowed confusion about his knowledge of hush payments to a pornographic film actress, and disparaged the special counsel’s Russia investigation, as well as railed against trade imbalances and scored a once-unthinkable meeting with the North Korean leader, to be held Tuesday in Singapore.

His daily torrent of tweets about the Russia inquiry, interpreted by his critics as distress signals, is more often than not a sign that he is less worried about the consequences of using the blunt force of his platform to fight back, according to three advisers.

People who did not work with Mr. Trump before the White House see his behavior as deteriorating; people who have worked for and with him for years say he has never changed, and there are simply fewer people around giving him a level of cover.

“Trump understands the overwhelming power of modern mass communications,” Mr. Bannon added. “Trump gets what the media itself has forgotten about themselves.”

The president, whose view of executive power has often crashed into the realities of Washington, is now focused on flexing what muscles he can — including issuing a series of pardons and repeatedly suggesting he has the power to deliver one to himself — and making decisions that do not require him to build coalitions of support. He now dictates to aides what he would like to see happen, as opposed to seeking a range of views, as predecessors may have done, people close to him say.

In one example, John R. Bolton, the national security adviser, has mostly followed the president’s lead instead of making efforts to maintain detailed briefings for him. Mr. Bolton has not won his way into Mr. Trump’s inner circle, particularly after comparing North Korea to Libya. (That country’s former leader Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi gave up his pursuit of nuclear weapons, and was later killed during an uprising.)

Rather than trusting the people around him, Mr. Trump has taken to working the phones more aggressively to seek counsel from outside voices, particularly two of his longest-serving advisers — Corey Lewandowski, his first campaign manager, and his longtime friend David Bossie.

Among the president’s other confidants is Scott Pruitt, the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. Mr. Trump has dismissed the advice of several aides who have tried to persuade him to fire Mr. Pruitt in light of the growing questions about misuse of his authority. The two speak frequently, and the president enjoys discussing his negative view of Jeff Sessions, the attorney general, with the embattled E.P.A. leader.

On Friday, the president told reporters that Mr. Pruitt “is doing a great job within the walls of the E.P.A.,” but that “outside, he’s being attacked very viciously by the press.”

Being either ignored or attacked by Mr. Trump can be demoralizing, and the staff churn that was constant during Mr. Trump’s first year has not slowed. Kathryn Dunn Tenpas, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who has studied White House turnover over the last six administrations, said that Mr. Trump’s staff turnover sat at 51 percent. By the time of the midterms, Mr. Trump — who, Ms. Tenpas said, has shown a tendency to move people into new roles rather than hire from the outside — will lead an emptier White House than his predecessors had.

Mr. Trump’s reliance on outside advisers, she said, also signals an “emasculation” of the chief of staff in the White House, who is meant to serve as the president’s confidant and gatekeeper.

“It seems as though Chief of Staff Kelly is losing power by the day,” Ms. Tenpas said. “It’s almost like a battery that’s draining. I’ve not seen any presidency operate effectively without putting somebody in there that you respect and you can trust.”

Mr. Kelly, several West Wing advisers say, is beaten down. His newly named deputy chief of staff, Zachary Fuentes, a young former military aide with no political experience, has earned the mocking title of “deputy president” over his behavior as a proxy for Mr. Kelly. But Mr. Kelly has developed an uneasy truce with the president, and he is among those traveling abroad with Mr. Trump this week.

Back at the White House, one of Mr. Kelly’s deputies, Mr. Hagin, whose connections to the Republican establishment have been a target of Mr. Trump’s outside advisers, is looking for a way out: He is said to be considering departing for a high-ranking job at the C.I.A., according to The Washington Post.

Chris Whipple, author of “The Gatekeepers,” a history of White House chiefs of staff, said in an interview that the president was taking the wrong lessons from his time in office.

“The lesson of the first year and a half of the White House is not that the president needs fewer guardrails,” Mr. Whipple said. “He needs more. There’s a huge difference between confidence and competence.”

As Mr. Kelly has receded from some of the managerial aspects of his job, a series of fiefs and empire-building efforts have sprouted in the areas of trade and national security. Without Gary D. Cohn, the process-focused former director of the National Economic Council, at the White House, the Treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, has tried to attain more power as the council’s staff has dwindled.

Even as his administration faces a series of diplomatic high-wire acts, including persuading Kim Jong-un, the North Korean leader, to give up his nuclear arsenal, Mr. Trump has remained fixated on leaks back home. He has recently pitted aides against each other in his search to find those who may be disloyal.

“Is he the leaker? Is she the leaker?” Mr. Trump asks visitors to the Oval Office, or outside advisers he talks to on the phone, whenever the names of specific staff members come up.

Some aides have sought to stoke the president’s fears about leaks, trying to identify people who could be disloyal: At least one senior aide is dropping inaccurate stories into the West Wing rumor mill to identify people who speak to reporters.

The communications office is likely to lose several staff members, some voluntarily but most at the request of a president who often complains that he has the biggest communications team and still gets terrible press.

On other issues, including trade — which roiled the Group of 7 summit meeting on Friday and Saturday, and which people close to the White House say will define the rest of the president’s second year — Mr. Trump has ignored the warnings of some advisers and has instead sought out people who will find ways to get done what he wants accomplished.

When the president could not quickly enlist the support of Robert E. Lighthizer, the United States trade representative, to find a way to make national security an issue with regard to imported automobiles, he circumvented his trade expert and asked Wilbur Ross, the commerce secretary, to carry out an investigation.

Ms. Tenpas, the staff turnover expert, said that, as the midterms approach, many talented people are likely to shy away from filling empty roles in a West Wing where the president believes he can function as his own chief of staff, spokesman and human resources manager.

“I think Trump has run through the first string of people pretty quickly,” she said. “If the patterns hold, we’re going to see another huge number of departures simply because people are exhausted and ready to move on.”

NEW YORK TIMES

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.