ERBIL, Iraq — Kurds across northern Iraq lined up Monday morning to vote in a referendum on whether to seek independence for an autonomous Kurdish region that has yearned for nationhood for more than a century.

ERBIL, Iraq — Kurds across northern Iraq lined up Monday morning to vote in a referendum on whether to seek independence for an autonomous Kurdish region that has yearned for nationhood for more than a century.

Despite withering criticism from the Iraqi government and the United States, voters marked simple paper ballots with boxes offering a “yes” or “no” choice on whether to embark on a path toward an independent Kurdistan.

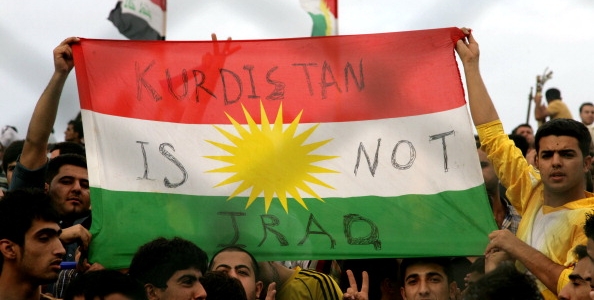

Some Iraqi Kurds were in a defiant mood, reflecting the region’s determination to withstand resistance from the international community, which fears the vote will unleash ethnic conflict and further destabilize Iraq. The Kurds’ two much larger neighbors, Turkey and Iran, have threatened to close borders and impose other sanctions.

“When I voted, I didn’t think for one second of Turkey or Iran and their threats — I’m not worried about them,” Rashid Ali, 61, a Kurdish retiree, said after voting at a public school in Erbil shortly after polls opened at 8 a.m.

A convincing “yes” vote, which is expected, would not lead to independence anytime soon. But Kurdish leaders believe a broad public mandate would provide leverage in any negotiations with Iraq on the Kurdish region’s push toward independence.Even as Kurds flashed ink-stained forefingers certifying they had voted, the referendum was fraught with risks that could further isolate and marginalize the landlocked enclave.

The Iraqi prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, said Sunday night that Iraq would “take the necessary measures to preserve the unity of the country.”

The Iraqi government, which considers the vote illegal, demanded that the Kurdish government surrender control of its international border posts and give up revenue from its oil exports to Turkey, the region’s single biggest source of income.

At Iraq’s request, Tehran halted flights on Sunday between Iran and the two international airports inside Iraqi Kurdistan. Kurds now worry that Baghdad will close airspace over the region.

Turkey and Iran, who fear the vote will foment unrest among their own Kurdish minorities, are conducting military exercises on their borders with Iraq near Kurdistan.

In a speech in Istanbul, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey threatened possible military intervention and warned that his country could shut down a pipeline through which Iraqi Kurdistan sends crude oil into Turkey.

Referring to a Turkish intervention in Syria last year, he suggested that Turkey could take similar action in Iraq. “We may enter at night without warning,” he said.

Mr. Erdogan also said a border crossing from Turkey into northern Iraq had been closed in one direction. He added that Turkey planned to shut it down entirely.

The Kurdish region’s president, Massoud Barzani, said on Sunday that the Kurds’ “partnership” with Iraq was over. He said that Iraq’s Kurds could no longer tolerate living in a “theocratic, sectarian state,” a reference to Iran’s considerable influence on Mr. Abadi’s government, which is dominated by Shiite Muslims.

“From now on, Kurdistan will be a neighbor of Iraq, but not part of it,” Mr. Barzani said.

Voting was also underway on Monday in several contested, ethnically mixed areas of northern Iraq claimed by both Iraq and the Kurdish regional government. Kurdish fighters known as pesh merga seized control of those areas in 2014, after the Iraqi Army collapsed and fled an assault by Islamic State militants.

The referendum’s extension to contested areas has angered Baghdad, as well as many non-Kurdish residents who want to remain citizens of Iraq.

Especially contentious is Kirkuk, an oil-rich city inhabited by Arabs, Kurds, Turkmens and smaller ethnic groups. Baghdad ordered the national police there not to provide security for voting sites, which were to be patrolled by Kurdish security police. In addition, Turkey fears that Turkmens living in disputed areas could be threatened by Kurdish attempts to include them in any future state.

Kurdish officials said referendum results would be announced within 72 hours. They said 3.9 million people were registered to vote, including residents of the disputed areas, at 1,700 polling locations.

The referendum, which is nonbinding outside the Kurdish region, is expected to pass by a comfortable margin, especially after two Kurdish political parties that had opposed the measure said Sunday night that they would support it.

Turnout will be a significant gauge of the depth of opposition to the vote among many Kurds, who say the region lacks the democratic institutions necessary for nationhood. Some Kurds who favor independence eventually, but not now, are expected to register their displeasure by staying home.

There is a significant contingent — including a “No, for Now” movement — that opposes Mr. Barzani, and accuses his government of corruption, incompetence and nepotism.

The United States had pressured Kurdish leaders to cancel the vote, warning that it could it could set off ethnic conflict, fracture Iraq and undermine the American-led coalition against Islamic State militants. The White House called the referendum “provocative and destabilizing,” and the American envoy to the region said it had no prospects for international legitimacy.

Despite stating its opposition, the United States has significant military and intelligence assets in Iraqi Kurdistan. Kurds are counting on relations with the United States continuing as usual once the referendum is completed and the rhetoric becomes less heated.

Kurdish leaders believe they have a trump card in the pesh merga fighting force, which has proved indispensable in battles against the Islamic State. Several Kurdish voters interviewed on Monday predicted that Washington would gradually temper its criticism, reflecting widespread faith in enduring American support.

Pesh merga fighters, like the Iraqi Army, have received American training and weapons. They have fought Islamic State militants alongside Iraqi government forces, which include Shiite militias supported by Iran.

Protected from Saddam Hussein’s troops by an American no-fly zone in 1991, the Kurds carved out an autonomous enclave in northern Iraq. It is home to an estimated four million to five million Kurds, who overall make up 15 to 20 percent of Iraq’s population.

For decades, Baathist regimes in Baghdad sought to eliminate Kurds and replace them with Arabs. Kurdish villages were razed, families were banished to internment camps, and tens of thousands of Kurds were executed.

Those atrocities contributed to a deep conviction among many Iraqi Kurds that only an independent Kurdish nation could guarantee their security.

Mr. Barzani said on Sunday that he was ready to begin negotiations with Baghdad over borders, security arrangements, oil income and other mutual interests even if it took two years or more. Iraq has said it will ignore the vote.

“The sun will rise in the east and we will negotiate,” Mr. Zebari said Saturday. “Statehood takes time.”

Hoshyar Zebari, Iraq’s former foreign minister and a leader of the referendum effort, has stressed that the region will look no different the day after the vote than it did before.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.