Sheikh Baker al-Rifai has for six years helped Syrian refugees in Lebanon register newborns, bury their dead, and navigate disputes with local police. In a country where many view refugees with suspicion, few could be more sympathetic to their plight.

But he is now impatient for them to pack their bags and leave.

“It is absolutely necessary that refugees return,” says Mr Rifai, a former Muslim religious leader in Baalbek, in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, an area dotted with ramshackle refugee camps made of tarp tents. “It’s not a matter of choice. Today, the question is how do they want to go back: Voluntarily, or by force?”

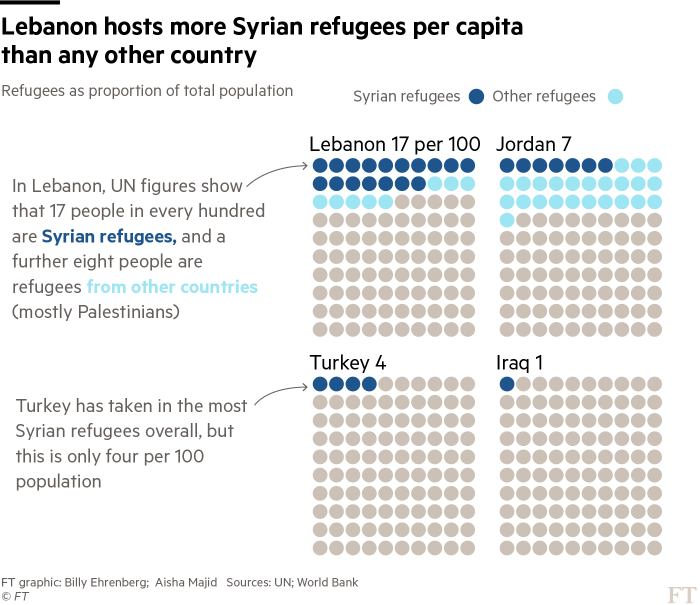

His sentiments reflect rising tensions between Lebanon’s 4m people and the nearly 1.5m Syrian refugees who fled into their country, a phenomenon that could have broader consequences for the region. Pressure on refugees to return to a nation wracked by conflict could push them to join the hundreds of thousands of Syrians who have fled to Europe — or spark violence in Lebanon, one of the few states in the region not mired in conflict.

For Lebanon, there is a historic element to this wariness — Palestinian refugees who fled there after the 1948 Arab-Israel war became involved in Lebanon’s 15-year civil conflict. Many from Lebanon’s Christian and Shia communities have long worried that the mostly Sunni Syrian refugees pose a threat to their country’s precarious demographic balance. But now even Sunnis such as Mr Rifai are growing weary of refugees he perceives as an economic burden and security risk.

“Let’s say only 1 per cent of these displaced people are infiltrated by terrorists,” he says. “If you have a town with 100,000 refugees, that means you have 1,000 terrorists there. We have a ticking time bomb here. We don’t know when it will go off.”

The mood toward refugees turned darker in recent weeks after the army raided a camp near Lebanon’s border town of Arsal, seeking militant infiltrators. At least one man in the camp blew himself up, according to a municipal official, who said the army rounded up some 400 Syrian refugee men. Around 150 remain in custody and four people died in detention. The Lebanese army investigators deemed the cause of their death “health conditions”. But human rights activists said their bodies were beaten and bruised.

Refugees across Lebanon planned to protest, but they met a swift backlash. At least one video emerged of men beating up a refugee on the streets of Beirut. Lebanese politicians seized the moment to argue that the refugees should go home now that the Syrian regime has recovered more territory. But forcing people to return during a conflict, rights activists say, defies international law.

‘No way to go back’

Many Syrians, such as Osama, a young refugee Mr Rifai is helping, see no hope for going home as long as President Bashar al-Assad remains in power. He says he fled Syria four years ago, after spending a year in a regime prison after evading conscription to the army. He was tortured and spent a month in solitary confinement, he says.

“My house was destroyed, my family and friends there are all dead . . . After all that I experienced, there is no way to go back,” he says. “The only solution is to get out of this whole region. Send me to India, to China, to Sudan — anywhere in Africa, I don’t care. As long as it gets me as far away as possible from Syria.”

Lebanese say these refugees are a burden to their stagnating economy, which has been hit hard by the Syrian conflict. They complain of lost jobs and lower wages, and that state services such as water, electricity and healthcare are collapsing under the strain of the refugees.

FINANCIAL TIMES

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.