By Anne Applebaum

By Anne Applebaum

“We are following a foreign policy which is the outward expression of the democratic faith we profess. We are doing what we can to encourage free states and free peoples throughout the world, to aid the suffering and afflicted in foreign lands, and to strengthen democratic nations against aggression.”

— Harry S. Truman, State of the Union, 1949

Since President Truman spoke those words nearly 70 years ago, every successive U.S. president has, consciously or otherwise, taken them to heart. The ideas that the United States should “strengthen democratic nations against aggression” and maintain a network of “free states and free peoples” around the world led to the creation of powerful alliances in Asia, as well as a whole host of transatlantic and European institutions that have kept Europe safe, free, prosperous and allied with the United States: the North Atlantic Treaty Alliance, the Council of Europe, the European Union. Some of these institutions came with costs for the United States, but because they are the bedrock of American power in the world — because America’s allies promote American values and its interests around the world — no U.S. administration in seven decades has ever sought to undermine them.

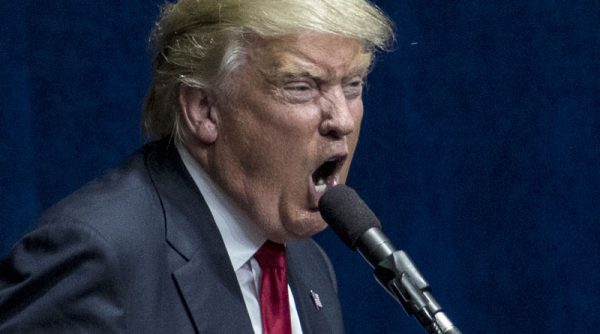

When Donald Trump is inaugurated this month, that will no longer be the case. Trump has made clear that he is no longer interested in promoting America’s “democratic faith,” or an America that maintains a special relationship with “free states and free peoples.” We already know that he envisions, instead, an America that does deals in the name of a narrowly defined national interest. But will he go further than that?

In the past few weeks, some of America’s oldest and closest allies in Europe have begun to fear that Trump’s White House may not just neglect them, which has happened often enough in the past, but actually seek to undermine them and their institutions. The link between Trump, his senior counselor and chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon and Breitbart News, the website Bannon was running until he went to work for Trump, is what worries them most. Flush from its success in the United States, Breitbart now seeks to monetize anti-immigration and racist sentiment in Europe, too, promoting it, selling it and using it to elect populist politicians who are just as skeptical of NATO as Trump, and who will do their best to destroy the European Union as well.

First up are Germany and France, where Breitbart has announced, in advance of imminent German and French elections, that it intends to open new German- and French-language websites. The worldview of these future sites can be predicted: Breitbart has produced gushing coverage of the National Front, the radical right-wing French political party that is openly funded by Russian moneyand that advocates, among other things, the end of NATO and a French withdrawal from the European Union. Soon after the U.S. election, Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, niece of Marine Le Pen, the National Front leader, tweeted, “I answer yes to the invitation of Stephen Bannon, CEO of @realDonaldTrump presidential campaign, to work together.”

Breitbart also frequently and approvingly quotes the Alternative for Germany (AfD), Germany’s new anti-immigration party, producing banner headlines and articles composed entirely of attacks on Angela Merkel, the German chancellor. Does Bannon support the rapid growth of the AfD as well as the National Front? It too has leaders who express admiration for Russia, deep dislike of the United States and skepticism of NATO.

More to the point, does Trump support anti-American politicians? We don’t know, but there are reasons he might. The answer could lie in Bannon’s nihilism, in Trump’s own stated belief in the restorative power of crisis and violence(“When the economy crashes, when the country goes to total hell . . . you’ll have riots to go back to where we used to be when we were great”) and, perhaps, in this White House’s close links to Russia.

Of course the destruction of the transatlantic alliance and the European Union could cause uncertainty and a decline in living standards for Europeans, not to mention violence or real chaos. Of course instability in Europe is not in the interests of U.S. business or politics, either. But a few would benefit. Russia would once again become a major European player. Plutocrats could make money out of the disaster — hedge funds famously prefer instability. In the wake of the revolution, all kinds of unexpected people might rise to power.

Clearly there are other members of Trump’s team who won’t like the idea of chaos in Europe. It’s hard to imagine the collapse of NATO appealing to a James N. Mattis or Rex Tillerson. But because no one knows who will have the president’s ear, Merkel, in the words of one German weekly, has already started “preparing for the worst.”

It’s an existential moment for all of Europe’s leaders, most of whom are only just beginning to grapple with the fact that Russia wants to destroy the Euro-American alliance.

A few generations after Truman, will they have to prepare for an American government that wants to do so too?

WASHINGTON POST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.