Many of Syrian President Bashar al Assad’s supporters are hailing the imminent recapture of Aleppo as the beginning of the end. But across the rest of the country, the war rages on.

Many of Syrian President Bashar al Assad’s supporters are hailing the imminent recapture of Aleppo as the beginning of the end. But across the rest of the country, the war rages on.

On Wednesday, the Syrian government was preparing to announce its capture of all rebel held areas of Aleppo, the regime’s most significant victory since the start of the country’s brutal civil war in March 2011.

The Syrian government has been trying to retake the city, once the country’s economic capital, since March 2013.

After false starts and one failed offensive in February 2015, the last road to rebel-held east Aleppo was cut off in July 2016, while Turkey has finally closed its borders to the rebels.

‘Only half a president’

For many observers, the recapture of Aleppo will be the decisive moment in the war.

Fabrice Balanche, Syria specialist at the Washington Institute, compared it to the 1942-1943 Battle of Stalingrad, which marked the turning point of the Second World War.

Balanche said the victory against tough opposition was crucial for Assad, who was “only half a president” without complete control of Aleppo.

“With this victory, he can genuinely present himself as president of all of Syria,” Balanche told FRANCE 24.

David Rigoulet-Roze, editor of the Orients Stratégiques review, and a Middle East expert, believes the fall of Aleppo will be a military and ideological “tipping point”.

Since the summer of 2012, when the city was cut in two by the rebel offensive, “there was an idea that the rebel-held area was an experiment in urban government in opposition to Assad’s regime,” he told FRANCE 24. “The recapture of these rebel-held areas marks the failure of any realistic political alternative to the regime.”

Still several rebel strongholds

Even if the fall of Aleppo marks a definitive turning point for the Damascus regime, it does not mean, by any stretch, that the Syrian war is over.

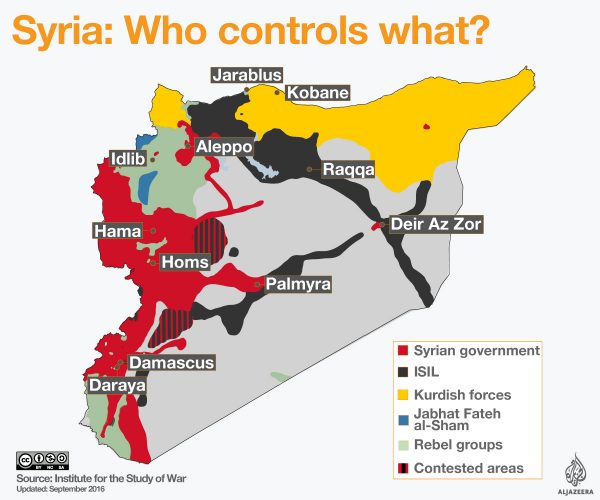

“The Nazi attempt to take Stalingrad failed in March 1943, and the Second World War dragged on for another two years,” said Balanche. “A large swath of Syria remains well beyond the control of the Damascus regime. The Idlib province, for example, is a stronghold of Fatah al-Sham [formerly al-Nusra Front and other rebel groups]. This area is likely to be the next target for the Syrian army.”

“This will be another very big battle, as the area is densely populated and there are between 50,000 and 60,000 rebels holding out there,” he said.

Add to these numbers countless civilians, and the families of rebels who have fled the fighting in Aleppo and other urban areas that have fallen to the regime, such as the Waer district of the city of Homs.

Across the rest of the country, pockets of rebel resistance are holding out in towns such as Douma, Harasta and Ghouta, all on the outskirts of Syrian capital Damascus.

“The surrenders will multiply around Damascus,” said Balanche. “Douma does not want to suffer the same fate as Aleppo.”

IS group retakes Palmyra

At the same time as many Syrians, either civilians exhausted by war or ardent supporters of the regime, were hoping that the recapture of Aleppo would be the beginning of the end of the war and mark a return to peace and a semblance of prosperity, the ancient city of Palmyra fell to Islamic State group rebels over the weekend.

It is a particularly bitter setback for the Syrian army and its Russian allies, who had wrested control of Syria’s “archaeological jewel” from the hands of the IS group in March 2016.

The coincidence of Palmyra’s fall to the IS group coming at the same time as the closing stages of the Aleppo battle is a stark reminder of just how complex and multi-faceted the Syrian war is, and how far the conflict is from being resolved.

“It isn’t a huge surprise that the regime lost Palmyra while all Assad’s forces were focussing on Aleppo,” said Rigoulet-Roze. “The Syrian regime cannot be on all fronts at the same time.”

A fractured future

In the long term, a gradual retaking of rebel-held areas could herald a period of less frequent fighting and attacks.

Balanche and Rigoulet-Roze both agreed that the conflict in Syria could, to some extent, follow the experience of Iraq after the official cessation of hostilities: a relative calm, regularly shaken by bloody attacks.

“But Syria as it was before 2011 no longer exists,” said Rigoulet-Roze, pointing out profound changes in the country’s demographics as a result of more than five years’ war. “We are seeing the emergence of various different zones of influence in Syria.”

His view is shared by Balanche: “There is evidence of a Russian-Iranian protectorate, but also a zone of Turkish influence in the north, which Ankara has always wanted, and which will be a safe haven for Sunni rebels. The Kurds are also likely to enjoy de facto autonomy.”

FRANCE24

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.