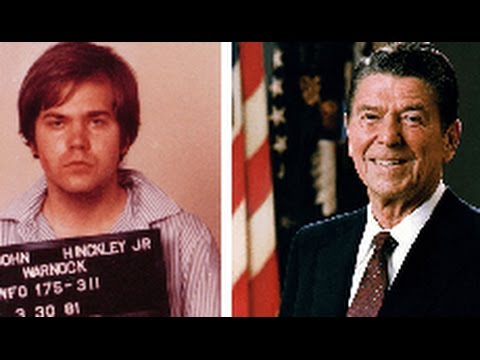

John W. Hinckley Jr., wearing a baseball cap and carrying a small bag, on Saturday afternoon stepped into his Williamsburg, Va., home — he can call it that now — 12,948 days after his attempt to assassinate President Ronald Reagan shook the country and prompted an enduring debate about crime and punishment.

John W. Hinckley Jr., wearing a baseball cap and carrying a small bag, on Saturday afternoon stepped into his Williamsburg, Va., home — he can call it that now — 12,948 days after his attempt to assassinate President Ronald Reagan shook the country and prompted an enduring debate about crime and punishment.

Hinckley’s court-ordered transition from a mental hospital in the District to a gated resort community, where he will live with his 90-year-old mother, has forced residents of this small town to grapple with an unsettling reality: Living among them is a former would-be assassin who, according to medical experts, has recovered and is no longer dangerous.

Thirty-five years after the shooting, and after scores of temporary visits by Hinckley, the town of 15,000 is decidedly ambivalent about its newest resident.

As Hinckley made his way in a black SUV from St. Elizabeths Hospital to Williamsburg on Saturday, Mary Lou Yeager, a 78-year-old widow who lives a few doors down, wondered about her safety.

Across town at a bookstore, where Hinckley has been spotted during past visits, Felix Brandon, 79, said he believes that Hinckley deserved to be in prison because what he did was “unpardonable.”

And at a recreation center where Hinckley likes to exercise, Tom Leitch, 56, said he thinks that Hinckley, now 61, is just “an old man who poses no threat.”

The responses reflect the challenge Hinckley faces in rejoining the community, a key factor in whether his move will be a success, according to medical experts.

At the time of the shooting, Hinckley was a troubled 25-year-old obsessed with actress Jodie Foster and the movie “Taxi Driver.” He began stalking Reagan and on March 30, 1981, shot him, along with White House press secretary James Brady, a U.S. Secret Service agent and a D.C. police officer. Brady suffered brain damage and died of his injuries in 2014. The others recovered.

Hinckley’s successful insanity defense before a jury outraged the nation and prompted changes that narrowed the application of that legal strategy.

Some in Kingsmill, the gated community Hinckley will call home, are skeptical that he is no longer a threat.

“It’s not a matter of forgiveness but a matter of security,” said Joe Mann, a vocal critic of the release who lives about a half-mile from Hinckley’s mother.

Hinckley’s longtime defense attorney, Barry Wm. Levine, called that “misplaced fear,” citing a lengthy court opinion based on medical experts who testified that Hinckley was stable and had been in remission for more than 27 years.

“If those people who have concerns were fully informed, they’d have nothing to worry about,” Levine said.

The high-profile release spotlights a segment of the population who typically go unnoticed: People who have settled back into autonomous lives after being found not guilty of violent crimes because of their severe mental illness.

In Virginia, 265 people are living in communities after being found not guilty of a crime by reason of insanity. In each case, the person was treated at a state mental hospital and released by mental-health and court officials with conditions. The vast majority of those people — 84 percent — had been charged with violent crimes, including murder and attempted murder, according to state officials.

State officials also said there has been a very low rate of recidivism since 1992, when Virginia began the reintegration program.

“We have had very few reoffenders,” said Michael Schaefer of Virginia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services. “I can count them on one hand.”

In Hinckley’s case, the judge imposed dozens of conditions on Hinckley’s release. Among them: He must remain within 50 miles of Williamsburg, report to a psychiatric team there and continue to undergo treatment.

The judge also said that Hinckley could be sent back to St. Elizabeths if he relapses or violates the terms of his release.

Hinckley started his three-day visits to Williamsburg a decade ago. The length of his leave gradually increased as he made strides in rejoining the community.

Until Saturday, he was spending 17 days each month at his mother’s home. He has gone bowling, attended lectures and concerts, and volunteered at a nearby church. But his initial attempts to join volunteer groups and get a job have been repeatedly rejected, according to court records.

He has, however, been embraced by the Unitarian Universalist Church, where he has volunteered as a landscaper and now sells donated books to benefit the church.

Les Solomon, president of the church and a mentor, said he hoped the experience will allow Hinckley to turn the book-selling into a part-time job.

“John loves books, and he is so appreciative of what we do,” said Solomon, who invites Hinckley to his home about once a month. “We feel there’s an opportunity to be of service to him, and it’s a very rewarding experience.”

Hinckley is also interested in music and photography and developed a fondness for cats at St. Elizabeths Hospital.

He told a therapist that the only thing he’d miss about the hospital were the stray cats he feeds every morning, according to court records. When he entered his home Saturday afternoon, a driver followed him with a small pet carrier.

Acquaintances and neighbors in Williamsburg described Hinckley as quiet and reserved. In the past, he has spent his unsupervised time at shopping centers, bookstores and cultural events.

“He tried hard to make friends, but when people found out who he was, they’d shut down,” said John J. Lee, a psychiatrist who monitored Hinckley during his first visits to Williamsburg in 2006 and 2007.

At a neighborhood picnic three years ago, Hinckley wore a baseball cap and dark sunglasses and kept to himself, said neighbor Jack Garrow. “He hardly said a word,” Garrow added. After the picnic, Garrow turned to his wife and said: “Do you know who that was?”

Garrow, a former rear admiral in the Navy, said he can’t forgive Hinckley for what he did but that he trusts the courts.

Many others interviewed in Williamsburg were not so sure.

“We don’t like it,” said John Kahler, 48, standing in his mother’s driveway on Saturday, just down the street from the Hinckleys. “Look what he did to Brady. Look what he tried to do to the president. Then the guy gets loose?”

Hinckley’s prior visits to Williamsburg were closely scrutinized. He has provided hour-by-hour itineraries of his activities for preapproval and has been trailed by Secret Service agents. He will continue to be monitored but will not have to submit the same accounting of his time.

Carol Jenkins, 80, was at the Barnes & Noble bookstore in the New Town shopping center Saturday, where Secret Service agents once spotted Hinckley perusing books about presidents and assassinations when he was supposed to be at the movies.

“I have mixed feelings,” she said. “On the one hand, I think you have to be held responsible for your actions. But I assume — you have to — that the folks involved in his case know what they’re doing.”

WASHINGTON POST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.