It was just three months ago that the 43-day legal fight between the FBI and Apple over demands Apple help authorities hack into an iPhone used by San Bernardino shooter Syed Rizwan ended.

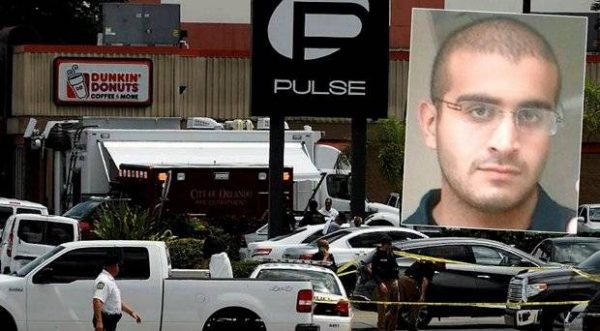

As law enforcement begins the task of investigating the life of the man behind the nation’s largest mass shooting at an Orlando gay dance club early Sunday morning, his digital footprint will be front and center.

This will be of special interest as Mateen is believed to have been at least partially radicalized through viewing extremist websites, FBI Director James Comey said Monday. He was, however, clear that the gunman did not appear to have been directed by the Islamic State or been a part of a larger conspiracy.

Very little is known so far about Mateen’s tech setup, but from selfies he posted on social media, it appears that Mateen used an Android smartphone at one point.

If that’s the case, law enforcement will face different issues accessing information on the phone than they did in the case of the iPhone used by the San Bernardino shooters in December.

The FBI acknowledged Monday that it has Mateen’s cellphone and electronics, but had no comment on what type of phone he used or whether encryption had surfaced as problem in accessing any information that might have been on it.

Google, maker of the Android smartphone operating system, also declined to comment.

It’s known that Mateen was using a phone during the course of the attack. At some point between 2 and 5 a.m. Eastern he called 911 and pledged his support to the Islamic State, or ISIS, according to the FBI.

During phone negotiations with police before they stormed the dance club where 49 victims died and 53 were injured, Mateen sounded “cool and calm,” Orlando Police Chief John Mina said Monday.

Legal issues to access the phone

All phone manufacturers require law enforcement to gain a search warrant before they give up information about an individual’s account.

It shouldn’t be difficult for law enforcement officials to get such a search warrant for Mateen’s phone, as it seems clear there is probable cause that the phone was part of an instrumentality of the crime, said Scott Vernick, head of the data security and privacy practice at Fox Rothschild in Philadelphia.

Google has been clear that it scrutinizes all such requests. It also publishes a Transparency Report in which it outlines how many requests for data it has received from law enforcement and how many it complied with.

However, if it turns out that Mateen’s phone was encrypted and therefore there is information on the phone that the FBI can’t get off the phone on its own, a host of new issues come up.

The FBI’s iPhone battle

These issues were much in the news this winter and spring as the FBI waged a very public court battle with Apple over its demand that Apple help the agency create a new operating system to allow it to break into an iPhone used by Syed Farook, the husband in the couple who killed 14 people in San Bernardino on Dec. 2, 2015.

Farook’s iPhone 5 came equipped with a program that allowed the phone’s contents to be wiped if more than 10 unsuccessful tries to determine the correct password were made. Apple refused to write a version of the operating system that would have allowed the agency to bypass that protection, saying to do so would fundamentally undermine the security of all iPhones.

The case finally ended when the FBI paid an outside party more than $1.3 million to break into Farook’s iPhone, using a method that has never been revealed.

Many flavors of Android

Whether a battle over Mateen’s phone will even happen is unknown.

First, it’s important to note that much of the information users typically access through their smartphones is available elsewhere, whether it’s email stored in the cloud, phone records stored with the user’s wireless company or purchases stored on the computers of Amazon and others.

If there proves to be information that is only available on Mateen’s phone itself, the issue the FBI faces to get it off the phone, if it is indeed an Android, will be different than they would have been were it an iPhone.

First, unlike iPhones, Androids come in literally dozens of types. Apple builds and sells all iPhones and the only major variations are via updates to its operating system.

Google, on the other hand, makes its Android operating system available to a plethora of handset makers. This means that each iteration of its operating system can be implemented in a slightly different flavor depending on the needs and desires of the hardware manufacturer.

Google also offers encryption on its phones but was later to the game than Apple. It began offering Android users a encryption option in 2011 and in 2014 turned on full encryption by default on its Lollipop operating system.

With the advent of Marshmallow, the 2015 operating system software, Google required Android phones to be fully encrypted, but only if they were “high performing” enough to be able to accommodate it.

According to an analysis by the Wall Street Journal conducted in March, fewer than 10% of the world’s Androids are encrypted. However it’s likely that a higher percentage of the Androids used in the United States are because users here tend to upgrade operating systems and to buy more powerful phones.

What company made Mateen’s phone, what version of the Android operating system it was running and whether it had encryption enabled is not know.

If Mateen’s phone were an Android and if it were encrypted, it’s unlikely Google could aid the FBI in accessing the information on it.

In November, Android’s lead engineer Adrian Ludwig said the company cannot access information on encrypted Androids.

Google “does not have any mechanism to facilitate access to devices that have been encrypted (whether encrypted by the user, as has been available since Android 3.0 for all Android devices, or encrypted by default, as has been available since Android 5.0 on select devices),” he wrote.

Should there be information on the phone that cannot be accessed elsewhere, and that is encrypted, Google could potentially find itself in the same place Apple was earlier this year — fighting demands that it aid the government in breaking its own user protections.

While the attack was “horrific,” the same fundamental privacy questions that came up in the San Bernardino case will still be in play here, said Fox Rothschild’s Vernick. There will be “tremendous pressure” on the maker of the phone to assist law enforcement in cracking it, said Vernick.

Going down the road “is a very slippery slope” for privacy, he said.

USA Today

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.