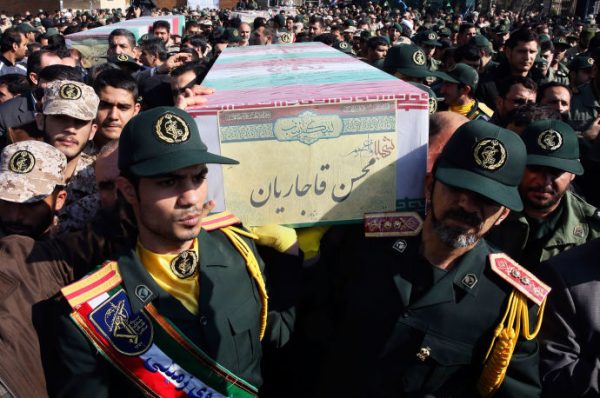

CREDIT PHOTOGRAPH BY VAHID SALEMI / AP

BY ROBIN WRIGHT

Iran is taking increasingly heavy casualties in Syria. A statement from the Revolutionary Guards announced last Saturday that thirteen of the corps’ élite forces were “martyred” in the escalating battle near Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, which has become the front line in the five-year civil war. Another twenty-one Iranians were wounded. It is, for Iran, the largest single casualty toll since the country intervened to rescue the regime of President Bashar al-Assad. The fighting took place in Khan Touman, a village nine miles south of Aleppo.

There’s no hiding the human costs in a war that is being played out graphically on social media. Syrian rebels immediately posted grisly photographs and videos of a pile of corpses dressed in camouflage, as well as photos of wallets with Iranian documents, identity cards, and currency.

The news has made front pages across Tehran. The newspaper Ghanian compared the fight for Aleppo with the Battle of Karbala, from the year 680—an event that was pivotal in the Islamic world and has symbolized tensions between Shiites and Sunnis ever since. In Karbala, a small group of Shiites were slaughtered by Sunnis of the Umayyad dynasty. Since then, Sunnis have dominated Islam—in terms of numbers, geographic range, resources, and power. Karbala also made martyrdom integral to Shiite tradition—and to Tehran’s concept of modern warfare.

In Syria last week, Iran’s Shiite forces were killed by an alliance of Sunnis known as the Army of Conquest, or Jaish al-Fatah, which is made up of Islamic extremist groups that includes the al-Nusra Front, Syria’s Al Qaeda franchise.

Tehran continues to maintain that its forces serve only in advisory roles, but the numbers dying on the battlefield challenge the claim. Between 2013 and mid-2015, Iranian news agencies identified more than four hundred martyrs. Since last September, another three hundred fighters have died in Syria, according to the latest month-by-month tally published by the Levantine Group, an independent Middle East risk-assessment firm. “Iran has suffered as many (or even more) casualties in the past six months than in the first two years of its operations,” the group reported. The two deadliest months were April (fifty deaths) and February (sixty-four).

In February, amid new peace efforts led by the United Nations, Iran withdrew a “significant number” of its Revolutionary Guards, according to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry. “Their presence is actually reduced in Syria,” Kerry told a congressional committee. “That doesn’t mean that they’re still not engaged and active in the flow of weapons from Syria through Damascus to Lebanon. We’re concerned about that.” But Iran has other forces in Syria. This spring, the government announced the deployment of special forces from the regular Army, in what was their first active engagement since the war with Iraq, in the nineteen-eighties. Within a week, four fighters were killed.

Iran has also deployed a large number of Afghan refugees, men who fled wars in their own country and have been stranded in Iran for years, even decades. These fighters are effectively stateless and mostly poor, with limited access to education or social services. Iran has recruited them for the Fatemioun Brigade, a largely Afghan unit organized under the Revolutionary Guards. (The name isderived from the Fatamid dynasty, which ruled a large chunk of the Middle East from 909 until 1171.)

The Afghans began showing up in Syria in 2013, initially to protect Shiite shrines. Iran calls them “volunteers,” but they were promised residence permits, better jobs, and other perks if they joined the equivalent of a foreign legion—and were threatened with deportation if they refused, according to Human Rights Watch. The BBC Persian Service reported that Iran is now deploying thousands of Afghans to fight alongside Syria’s own forces.

The Afghans—mainly drawn from ethnic Hazaras, who are Shiites and speak Persian—are now undeniably deployed on the front lines. Fatemioun’s two top commanders, both Afghans, died in battle late last year. More than half of the sixty-four Iranian fighters killed in April were Afghan auxiliaries, according to the Levantine Group. A year ago, Iranian media reported that at least two hundred fighters from the Fatemioun Brigade had died in Syria. The dead are given military funerals back in Iran, and the numbers keep mounting.

On Friday, Ali Akbar Velayati, a foreign-policy adviser to Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, flew to Damascus, where he told reporters, “Our assessment is that Syria is in a position of strength more than any other time.” He also praised Assad, saying, “I believe the Syrian President has shown that he can manage the country with prudence and bravery.” On Saturday, Velayati met with Assad and renewed his government’s pledge of support. “Iran will use all its means to fight against terrorists who are committing crimes in the region,” Velayati vowed. This promise clearly includes the martyrdom of even more Iranians and their Afghan proxies.

The New Yorker

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.