The last time Burma held a nationwide election, Aung San Suu Kyi languished under house arrest while her party’s landslide win was simply ignored by the country’s brutal military rulers.

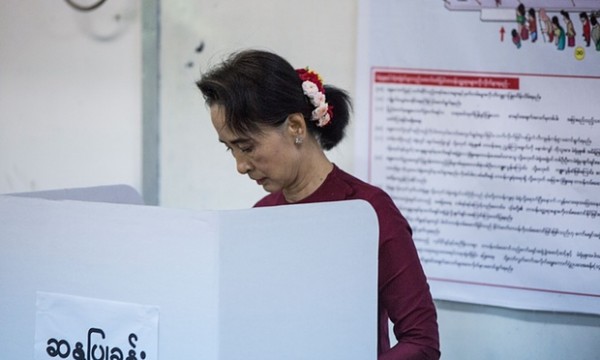

Twenty-five years later, the democracy champion cast her ballot Sunday morning at a Yangon polling station – the culmination of an exhausting few weeks of campaigning that has drawn large, jubilant crowds hoping this will be Burma’s fairest vote in decades.

“There is a strong upbeat atmosphere and there are huge queues outside the polling stations”, said Ismail Wolff, FRANCE 24’s reporter in Burma.

“Twenty five years ago that vote was not respected and there are a lot of hopes that this time around the military will accept the result.”

A vast media scrum greeted the 70-year-old as she swept into a polling station, dressed in a red top that matches the colours of her National League for Democracy party.

For Suu Kyi herself, the polls are a watershed moment in a life entwined with the turbulent political struggles of her homeland, shaped by decades of brutal junta rule that only began to ease in 2011.

The daughter of independence hero General Aung San, Suu Kyi, 70, has headed non-violent opposition to the country’s military rulers in a three decade role, which began almost by accident and has come at great personal cost.

Detractors say her reputation as a human rights icon has diminished in recent years as she plunged herself into Burma’s febrile politics, often choosing hard pragmatism over the idealism of her house arrest years.

But the Nobel Peace Prize winner still commands huge loyalty among supporters of her National League for Democracy (NLD) party and she remains a magnetic force for those wanting to see Myanmar shake off its military past.

Two decades under house arrest

But Suu Kyi has been here before and knows well that an election victory does not guarantee power in Burma, which is officially known as Myanmar.

Prior to her first stint of house arrest in July 1989, Suu Kyi spent months on a tiring – and often personally dangerous – campaign trail.

The NLD’s landslide victory the following year was dismissed by a junta, which immediately jailed many of Suu Kyi’s allies and kept her confined to her lakeside Yangon home for much of the next two decades.

Myanmar has since morphed from a hermit state into a booming economy open for business since the military ceded power to a quasi-civilian reformist government in 2011.

“But two big factors that haven’t changed are the charismatic bonanza enjoyed by Aung San Suu Kyi and the enduring grip of the military elite,” Nicholas Farrelly, director of the Myanmar Research Centre at the Australian National University, told AFP.

“For many Myanmar voters she is the defining figure of their country’s anti-authoritarian struggle. They imagine that the democratic destiny halted in the 1990s is now in reach.”

The generals seize power

Suu Kyi was born on June 19, 1945 in Japanese-occupied Rangoon – now called Yangon – during the closing stages of World War II.

Her father Aung San fought for and against both the British and the Japanese colonisers as he jostled to give his country the best shot at independence.

That goal was achieved in 1948 but Aung San was assassinated alongside most of his cabinet just months before.

Suu Kyi spent most of her early years outside of Myanmar, first in India after her mother was posted as ambassador there and later at Oxford University where she met her British husband.

After General Ne Win seized full power in 1962 he forced his own brand of socialism on Myanmar, turning it from Asia’s rice bowl into one of the world’s poorest and most isolated countries.

Suu Kyi’s elevation into a democracy champion happened almost by accident after she returned in 1988 to nurse her sick mother.

Soon afterwards protests erupted against the military, but were crushed in a crackdown that left at least 3,000 people dead.

The bloodshed was the catalyst for Suu Kyi. A charismatic orator, she found herself in a leading role in the burgeoning pro-democracy movement, delivering speeches to crowds of hundreds of thousands.

Sacrificing family life

During her house arrest years the junta offered to end her imprisonment at any time if she left the country for good – but Suu Kyi refused.

That decision meant not seeing her husband before his death from cancer in 1999, and missing her two sons growing up.

The military eventually granted her freedom in 2010, just days after flawed elections.

Two years later she entered parliament after the NLD swept a series of by-elections.

But even if her party wins this general election, she cannot become president thanks to a junta-era constitution that forbids anyone with offspring born abroad from taking the top spot.

She towers over the NLD and some observers question whether her star power has eclipsed the efforts of younger party members to emerge.

Suu Kyi has vowed to amend the charter. On Thursday she went further, declaring that she will occupy a position “above the president” if the NLD win.

In so doing she issued a challenge to the army as well as a reminder to her supporters that she occupies centre stage in Myanmar’s political drama.

But first she has to win.

FRANCE24/AFP

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.