The shrill Republican attacks on the Iran nuclear deal are an embar-rassment. Most global leaders share President Obama’s view that the agreement is prefer-able to any realistic alternative. It’s a diplomatic achievement that reinforces U.S. leader-ship, rather than undermining it. The damage to America would come from knee-jerk congressional rejection of the pact.

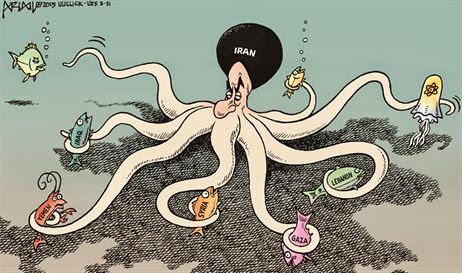

The GOP noise machine blasting the deal obscures the real question ahead, which is how to contain Iran’s meddling in the region. The right strategy is to present Tehran with a sharp choice: Either join serious negotiations to end the regional wars in Syria and Yemen, or face the prospect of much stiffer, U.S.-led resistance.

Stopping Iran’s destabilizing behavior is the priority in the Middle East, as senior Israeli, Saudi and Emirati officials agree privately, whatever the public commotion about the nu-clear deal. This essential task of confronting Tehran should be easier now that the Iranian nuclear program is capped for at least a decade. But Obama has to follow through on the regional front. Otherwise, Iran could extend its hegemony, which would harm the U.S and its allies.

“The technical side [of the nuclear agreement] is solid, but that was always our secondary concern,” one senior Gulf Arab official told me. “Our primary concern,” he said, is aggressive behavior in Syria, Yemen and elsewhere by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, financed by an Iran that will be freed from sanctions.

What’s the best way to confront Tehran on these regional issues? As with the nuclear problem, the right strategy is a combination of pressure (including possible military force) and diplomacy.

Let’s start with military containment. This was the real theme of the Camp David meeting with Gulf Arab leaders in May. Though pooh-poohed by commentators, the gathering produced a plan to improve arms transfers, special-forces training, joint military exercises and other measures to check Iran.

Building resistance to Tehran isn’t a money problem, but one of strategy and will. The Gulf Arab countries are already outspending Iran on defense by more than $100 billion annually. They just aren’t getting much bang for their buck. That should change, with closer cooperation.

Obama has had the “slows” in Syria, in part because he didn’t want to confront Iran’s proxy force there, the Lebanese Hezbollah militia, and risk blowing up the nuclear talks. But that excuse is now gone.

The U.S. should squeeze President Bashar al-Assad harder. His hold is weakening. In southern Syria, moderate fighters trained by CIA and Jordanian intelligence officers have gained ground. The Jordanians talk of building a safe zone there, with a 21st-century version of “strategic hamlets.” In northern Syria, U.S. airstrikes have allowed Kurdish fighters to seize a strip along the Turkish border, and the Turks are deliberating whether to impose their own border-security zone.

As the U.S. has seen in the nuclear talks, such pressure tactics are valuable if they push Tehran and its friends toward diplomacy. This tipping point may be near in Syria.

Moscow finally seems willing to discuss a brokered transition. Obama told New York Times columnist Tom Friedman that after talking recently with President Vladimir Putin, “I think they [the Russians] get a sense that the Assad regime is losing a grip over greater and greater swaths of territory inside of Syria and that the prospects for a takeover or rout of the Syrian regime is not imminent but becomes a greater and greater threat by the day.”

Obama spoke in his news conference last week about including Iran in a diplomatic settlement in Syria. “We’re not going to solve the problems in Syria unless there’s buy-in from the Russians, the Iranians, the Turks, our Gulf partners. It’s too chaotic. … Iran is one of those players, and I think that it’s important for them to be part of that conversation.”

Will pressure convince Iran that its interests are served by diplomatic negotiations on Syria and Yemen? Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif said in April that he would wel-come such talks. And Zarif has told Secretary of State John Kerry that Iran wants to play a different and less menacing role in the region.

But here’s the heart of the problem: Zarif doesn’t control Iran’s covert-action campaigns. They’re run by Gen. Qassem Suleimani, head of the Revolutionary Guard’s Quds Force.

What will convince the hardliners that it’s time to talk? Pressure, pressure, pressure … and then diplomacy. This crucial process will be much easier with the nuclear file closed.

WASHINGTON POST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.